The Annotated Nightstand: What Wendy Chen is Reading Now, and Next

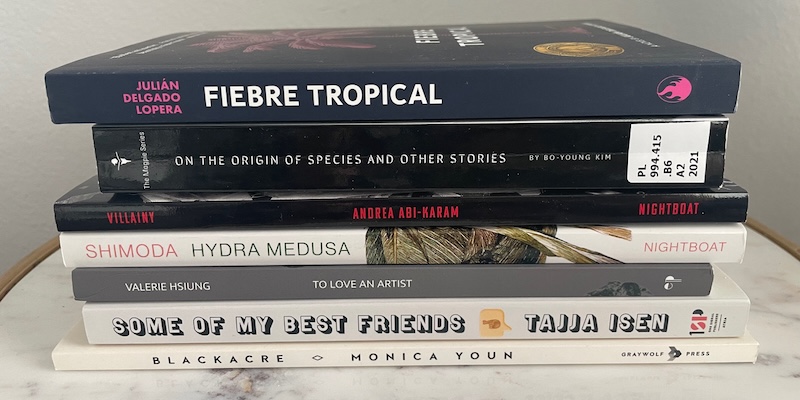

Featuring Julián Delgado Lopera, Bo-Young Kim, Brandon Shimoda, and Others

Poet Wendy Chen’s debut novel, Their Divine Fires, is a dynastic story that follows girls and women through four generations. Chen traces the family through periods of transition and turmoil in a country through the Chinese Revolution, the Second China-Japan War, the Cultural Revolution—from Liuyang, Nanjing, suburban Boston, and Beijing. Over a century of dramatic changes, Chen illustrates the ways in which such shifts inevitably leave families riven.

We begin in a place and time in which a doctor father says “If only you were a son” to his daughter, Yunhong, who shows a knack for healing. Throughout much of the novel, brothers and parents and beloveds are actors while girls are the acted upon. “Girls live as discarded things,” Yunhong tells her young daughter Yuexin as child hears a story about a stillborn baby. “By morning, the bundle would have disappeared, carried away in the mouth of a striped thing to be raised as a tiger. That is the only way girls can survive.”

All of the women, save for one, has a birthmark “the size and shape of a thumbprint” on their chests—if the thumb had been dipped in blood. The story of this birthmark is that, generations ago, a girl in their family who went missing in the mountains was found by her mother years later. “[A] matching mark bloomed on both their chests,” Chen writes, “so they would never lose each other again.”

This is only fully realized in the contemporary great-granddaughter of Yunhong, Emily. As someone tells Emily, “Sometimes, the past isn’t easy to remember. Sometimes, it’s best to move on.” And, also, in her mother’s lifetime during the Cultural Revolution, whenever she and her twin might find a piece of some larger, beautiful object that had been destroyed, “That was what happened to things from the old world—the world that came before the dawning of a new China. They had to be taken away and burned or hidden in the bottom of a chest.”

This proves as true of a shard of pottery or mother-of-pearl as family stories. But it is Emily who ultimately helps reforge lost connections, reveal family secrets. Kirkus states in its starred review,

Chen’s narrative is full of poignant family moments set against the larger canvas of history, while singular and recurring images link the fragmented narrative….Throughout, the author depicts women who find in themselves the strength to be more than the times might allow and in their families a sweet solace amid that struggle. A poignant, impressive debut.

Chen tells us about her to-read pile, “I’ve found myself drawn to the fantastic lately as I will be teaching a class on speculative fiction in the fall, so many of these books have some element of that. Other books are by authors I’ve recently met at events run by Black Mountain Institute, a wonderful literary organization here in Vegas.”

*

Julián Delgado Lopera, Fiebre Tropical

Lopera’s debut coming-of-age novel won the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction in 2021. Dan López writes in his lovingly personal review of Fiebre Tropical in Los Angeles Review of Books:

When I first heard about Juliana Delgado Lopera’s debut novel, Fiebre Tropical, I was ecstatic. Someone, it seemed, had experienced the same thing I had and wrote a novel about it, and did it in the captivating, riotously funny, code-switching, foul-mouthed voice of Francisca, a queer Latinx youth hating on the “stubborn bitch” of a Miami heat that continually reminds her not only that she’s no longer in her home town of Bogotá, but also that “this hell is inescapable.” It me, I thought, but no. What Lopera pulls from that heat in an inimitable voice is a bold, stylistic, and deeply moving examination of generational sadness, deferred desire, and the budding seeds of personal revolution that is entirely their own.

Bo-Young Kim, On the Origin of Species and Other Stories (trans. Sora Kim-Russell and Joungmin Lee Comfort)

Kim’s collection from the amazing Kaya Press was longlisted for the National Book Award in Translated Literature and a Publishers Weekly pick. In its starred review, Publishers Weekly writes,

This collection of seven stories and one essay from Kim (How Alike Are We) makes for a dazzling English-language debut. The essay, “A Brief Reflection on Breasts,” sets the tone for the gentle, humorous philosophizing of the collection as a whole. In it, Kim compares the value and necessity of science in science fiction to breasts on a woman, concluding that to focus on whether there is definitive science in a work distracts from the greater purpose of the genre…. And the title story finds robots debating a theory they consider to be laughable: that matter can grow organically. With a combination of subtle humor and poignant philosophy, Kim turns a genre-bending lens on human experience. This belongs on shelves next to Bradbury, Le Guin, and Murakami.

Also, can we talk about how unsettling this cover is? Simultaneously compelling/repelling me.

Andrea Abi-Karam, Villainy

In his preamble to an interview with Andrea Abi-Karam, Zeyn Joukhadar writes in them,

Against the backdrop of rising fascism and the deadliest year on record for Black and Latinx trans women, Andrea Abi-Karam’s new poetry collection Villainy (out now on Nightboat Books) asks: what can poetry do? In their work, the answer is often grounded in the body. The poems in Villainy engage with street protest and public sex; its subjects process grief, rage, and trauma by dancing, rioting, and smashing both poetic and literal fists against the glass traps capitalism sets for trans people…

Villainy critiques multiple kinds of violence with searing clarity, including American imperialism and the War on Terror; in fact, the Arabic word جرائم, on the cover, means ‘crimes.’ But this is a text that also seeks to complicate, on a deeper level, who and what is viewed as villainous in the eyes of the state and of society, who surveils and who is surveilled, who is allowed the requisite distance to grieve everyday injustices.

Brandon Shimoda, Hydra Medusa

In his review of Shimoda’s latest work for The Brooklyn Rail, Sean McCoy writes,

Hydra Medusa, written in Tucson between 2017–2020, in close proximity to the ongoing and programmatic incarceration of migrants and refugees at this country’s southern border, documents these overlapping realities of horror. Its poems, short talks, and catalogs of dreams do not so much resuscitate the past as pierce the thin scrim of the present to reveal the past as something breathing, lurking, pawing in the room beside us…

Formally, the poems comprise brief, left-justified lines of extraordinarily vivid imagery, layered with moments of incantatory repetition. The line ends are often unpunctuated; other norms of punctuation, spacing, and capitalization are broken to pattern the breath (Shimoda’s ear is a wand) and release the smoke of meaning. The desert is defined by its space and aridity. The lack of moisture permits all kinds of traces—bones, adobe, mirages, shell casings, clifftop altars—to persist far longer than in other environments. Hydra Medusa makes a pilgrimage to these remnants; many of these remnants reside in plain sight.

Valerie Hsiung, To love an artist

Renee Gladman says Hsiung’s To love an artist

is a work composed of dislocations—or rather, durations, expanses of dislocated voices, bodies, and narratives….When the poet writes, “Today, I speak a language of brutes,” I read the enfoldment of the cruelty our collective and respective histories into the languages of our subjectivity. Any expression of self or free-ness or united-ness is laden with material and intentions that do not belong to us. We have been mixed forever, we have been poured and burned through borders always, and are ourselves burned and poured through. And that is why it is useful to invent forms for the expression of our alloyed selves, to be non-knowing. To love an artist presents a despondent, broken, scattered form. Yet, it pulses with nuance and engagement. It’s beautiful, irreverent, and dangerously incoherent. It stays with you when you’ve stopped reading it and puts your seeing in disarray. It nourishes and it fails and it teaches. This is a book of refusal. It is a cosmography written as metallurgy; it wants to be the dust and it wants to be the friction.

You can access a “playlist” from To love an artist here.

Tajja Isen, Some of My Best Friends: And Other White Lies I’ve Been Told

Isen was one of The Annotated Nightstand‘s first guests when this column began two years (!) ago. Kirkus writes in its starred review,

Social justice—or what passes for it—falls under the scrutiny of [Isen]. As a biracial Black performer who has done voice-over work in the U.S. and Canada for two decades, Isen has seen firsthand the many ways in which well-intentioned ideas on race, gender, and culture—whether promoted by liberals or conservatives—can hurt people they aim to help. In the nine essays in this stellar debut collection, the author probes the gap between expectation and reality.

Her opening essay, “Hearing Voices,” sets the tone with its wry view of “the authenticity boom” that seeks to have Black animated characters voiced only by Black actors. ‘What Black characters?’ Isen asks, adding that in 2018, only three percent of the lead or co-lead roles in animated films were for women of color and that an insistence on perfect “phenotypic match[ing]” between an actor and character “would shut too many of us out until further notice….” [T]his book shows a bracing willingness to tackle sensitive issues that others often sweep under a rug. Fresh and intelligent critiques of popular North American ideas about race and gender.

Monica Youn, Blackacre

“Blackacre” is a legal placeholder (a la “Jane Doe”) when giving a hypothetical plot of land. Young wrote about her poetry collection Blackacre’s title sequence at The Poetry Foundation, and how included a “Blackacre,” “Whiteacre,” “Greenacre.” She continues,

We never start with a blank slate—each acre has been previously tenanted, enriched and depleted, built up and demolished. What are the limits of the imagination’s ability to transform what is given? On any particular ____acre can we plant a garden? found a city? unearth a treasure? build a home? When I was trying to write the poem that became “Blackacre,” I was trying to write something painfully private, painfully personal—about my ‘barrenness,’ my desire to have a child who would be genetically ‘mine,’ my increasingly irrational pursuit of that desire, its long-drawn-out failure, the fallout of recriminations and regrets, and my eventual decision to have a child by other means. I’ve never been comfortable with autobiographical material, and for years I circled the topic, trying innumerable false starts, wanting to approach the issue straightforwardly but failing at every attempt.