The Annotated Nightstand: What Translator Emilie Moorhouse is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Octavia Butler, Joshua Whitehead, Éric Chacour, and More

An English translation of the surrealist poet Joyce Mansour’s work has just arrived via City Lights in Emilie Moorhouse’s thoughtful and powerful translation. Born in England in the 1920s to Egyptian-Jewish parents, Mansour grew up in Cairo as a member of Egyptian the upper-class. Her mother died when she was 15, her first husband just three years later. Mansour moved to Paris at 20 and, while there, she was swept up into the second wave surrealist scene—with André Breton as a mentor. She began writing entirely in French, despite being bilingual in Arabic and English. In her translator’s note, Moorhouse explained what provoked her to find a poet like Mansour to translate. At the height of the MeToo movement, Moorhouse realized a particular purpose when finding her next translation project. Moorhouse explains, “I decided I needed to translate the writing of a woman who spoke openly and shamelessly about her desires.” In Mansour, she found a remarkable voice that seemed to terrify many into shunning her outright. For, as Moorhouse explains, Mansour’s “favorite subject matter happened to be two of society’s greatest fears: death and unfettered female desire.” In one poem, titled by its first line “Fièvre ton sexe est un crabe”/“Fever your sex is a crab,” she writes (via Moorhouse):

Déchirent mes doigts de cuir

Arrachent mes pistons

Ma bouche court le long de ta ligne d’horizon

Voyageuse sans peur sur une mer de frénésie

Tear at my leather fingers

Snatch at my pistons

My mouth runs along your horizon

A traveler unafraid on a frenzied sea

This captures the edge-of-your-seat urgency of Mansour. The images are like hairpin turns that never cease. It’s novel, strange, thrilling. Moorhouse complicates the poem further when she explains “the crab often represent[s] the cancer that ended her mother’s life…In Mansour’s work, love and death are inseparable.” In Tamara Faith Berger’s excellent interview with Moorhouse at The Rumpus, Moorhouse explains what, exactly, seemed to drive the lack of notable interest in Mansour’s work in France, despite the fact she published over a dozen powerful poetry collections. “I use the word chauvinistic because I think that certain French literary elite have this very precise idea of what ‘French’ literature is, and what ‘great’ literature is,” says Moorhouse. “[W]omen were allowed to write for children.” I’m so grateful to Moorhouse for her helping bring this remarkable poet’s work to English readers, and help expand our knowledge of women writers throughout the world—helping buck against the historical chauvinism Mansour endured. I know my bookshelf will be better for it. “Her work is defiant; even by today’s standards, it smashes taboos around female expression and desire,” Moorhouse explains. “She is Baudelaire minus the shame.”

Moorhouse tells us about her to-read pile, “I have a background as an environmental activist so I’m very interested in literature that weaves land and environmental themes into the narrative. I also teach literature to students who are often newcomers to Canada and I think for them it’s important to both read stories that echo their own experience and to discover unfamiliar voices, especially local Indigenous ones.”

*

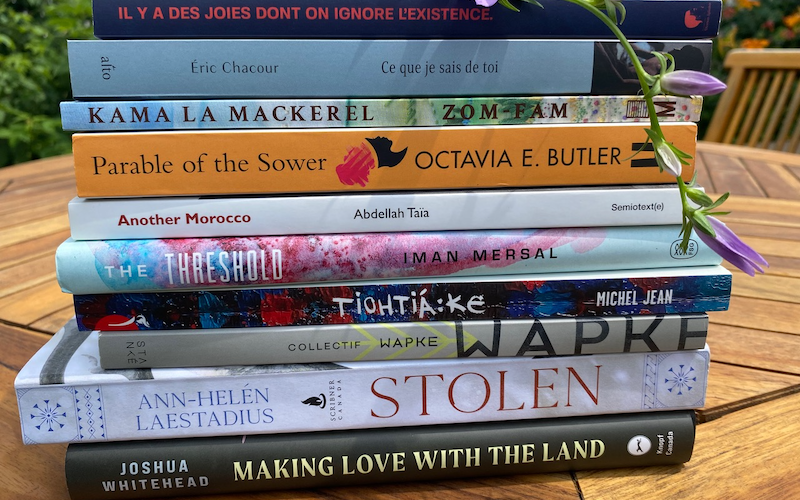

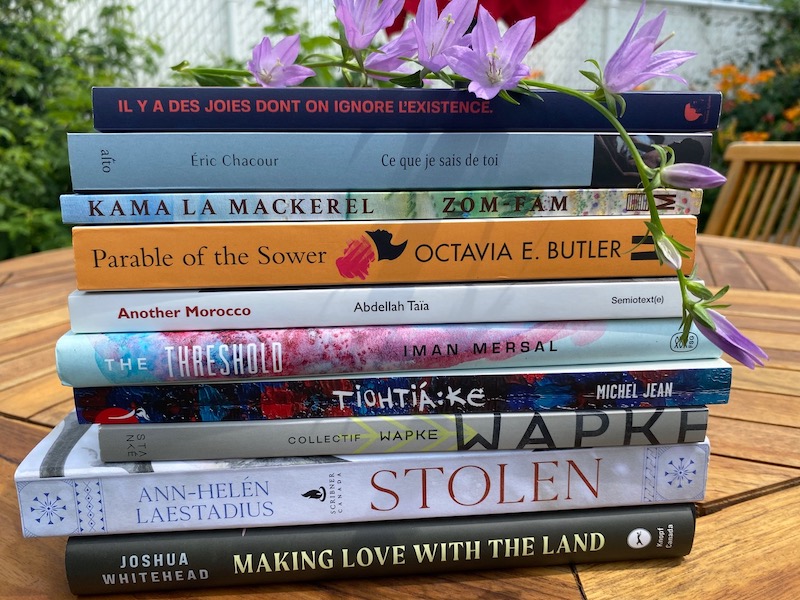

Cato Fortin, Madioula Kébé-Kamara, & Maude Lafleur (eds.), Il y a des joies dont on ignore l’existence (There are joys we don’t know exist)

The jacket copy for this Quebecois collection states (via Google translation…*cringe* please forgive me): “There are joys whose shimmerings and subtleties we do not know how to recognize, those joys which threaten to bring down what we had believed to be right and true until now. There are joys that cuddle us and slap us with the same hand, joys that only half relieve, but whose unusual beauty gives us the courage to stay a little longer. There are joys that make us breathe sighs of relief. I feel good here. I built a home there. A home is comfort, security, warmth. It is also the fire that inhabits us. The Diverses Syllabes editions were born from this fire. Of this fire and of a storm. From a wave of solidarity, desires to share, learn and laugh. It’s not about coming together to define who we are, but about gathering around a heart, of a core that reflects our many faces. We had to lift the veil on these joys whose existence we do not know, that they finally resonate.”

Éric Chacour, Ce que je sais de toi

Chacour, the child of Egyptian immigrants in Montreal who considered themselves Levantine, Syro-Lebanese, Chawam, or, most inclusively of “the community.” Ce que je sais de toi / What I know of you, Charcour’s first novel, just published this year, follows Tarek, a doctor in Cairo in the 1980s. Tarek’s connection with another person upends the clear path of his life. Chacour explains in an essay, “When I started writing this novel, it seemed obvious to me that one of my characters would be Muslim and the other Christian. Everything had to separate them: social status, family background, religion. My desire was not to oppose them, but rather to put a distance between them from the outset, to make their rapprochement unlikely. In an early version of the story, Tarek was a Coptic, as are the overwhelming majority of the millions of Christians in Egypt. But quickly, the idea that he could be Levantine imposed itself. Perhaps this minority within the minority seemed to me like the right setting for the story of his confinement, and that the decline it had known through the successive departures of its members added to the inner drama he was experiencing.”

Kama La Mackerel, ZOM-FAM

Artist, performer, translator, and writer La Mackerel’s poetry collection “mythologizes a queer/trans narrative of and for their home island, Mauritius.” ZOM-FAM (in Mauritian Kreol meaning literally “man-woman” or “transgender”) was a finalist for the Dayne Ogilvie Prize. The judges wrote, “Kama La Mackerel’s poetry is a sensuous and fiercely political exploration of gender, familial love, and the intergenerational impacts of colonization. Their multilingual, lyrical poems entrance with hypnotic rhythm and tell a story that spans decades and borders. La Mackerel captures the power of connections maintained in spite of the blunt, relentless pain of distance. Wooing the reader with a carefully orchestrated, gentle lapping of words, they then jolt us with earned, splashy staccatos of euphoria.”

Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

Octavia Butler’s powerful and disturbing novel made serious rounds at the height of the pandemic as she seemed, like an oracle, to predict so much of what we were enduring or succumbing to (ubiquitous racial and class difference defined by violence as well as the fallout of climate change—not to mention a leader with “Make America Great Again” as his tagline). So many people were buying and reading it, in fact, it was a New York Times bestseller—16 years after its original publication. I was able to see an exhibit of Butler’s ephemera several years ago, which included journals and letters, the early covers of her books that bore white figures despite the fact her main characters were Black. One quotation from a journal entry I keep pinned where I can see it. “Our past…teaches most of us that it’s best to expect nothing—so as not to be disappointed when you get nothing,” she writes. “No person who has absorbed that bit of corrosive philosophy needs an oppressor to keep her down.”

Abdellah Taïa, Another Morocco: Selected Stories (tr. Rachael Small)

Taïa left Morocco for France in the 1990s and began to write and make films and also, he had hoped, to live freely as a gay man. Taïa ultimately became the first openly gay man published in Morocco when he came out in 2006, having lived in France for years. I highly recommend listening/reading an interview Taïa gave with David Naimon regarding another book. Rachael Small, the translator of this collection, describes in an interview how she ran to the library after read Taïa had won the Prix de Flore. “[I] picked up the first book I could find, Une mélancolie arabe. I was instantly seduced by the raw, unabashed intimacy of the voice, the brutal beauty of his prose and storytelling, and I immediately started translating,” Small explains. “By that point, I had fallen so deeply for Taïa’s prose that rather than search for a different author to translate, I decided to go through the rest of his catalogue and began reading Mon Maroc, his first book…These very short stories felt much more guarded than the novels, but rich in a different kind of intimacy that was expressed through the intricate detail of daily life. It’s both like listening to a dear uncle tell tales of life in the old country and speaking with a new friend who is testing the waters, trying to decide what he can or can’t reveal to you about himself.”

Iman Mersal, The Threshold (tr. Robyn Creswell)

The Egyptian-Canadian poet Iman Mersal’s new work in translation is selected from her first four books. Creswell describes in an interview the complications of translating Arabic poetry into English. He writes, “English can do wryness, but Arabic verse has musical possibilities that I don’t think contemporary poetry in English can really capture. Because written Arabic is a literary language—it isn’t spoken except in formal situations—it’s possible to be grandly symphonic or virtuosically lyrical in a way that’s hard to imagine in English…With Iman the difficulty for an English translator is different, and I would say more manageable. In a poem about her father, she wonders whether he might have disliked her ‘unmusical poems.’ I don’t think they’re actually unmusical (I don’t think Iman does either), but their rhythms and cadences and sounds have a lot in common with the spoken language.”

Michel Jean, Tiohtià:ke [Montréal]

Jean is an Innu First Nations writer and journalist whose novel Tiohtià:ke [Montréal] contends with the difficult realities of houselessness within First Nations communities in Montreal. As the jacket copy states, “Before the arrival of Europeans, the island of Montreal was Mohwak territory. Tiohtià:ke is the Mohwak name for the island of Montreal. Elie Mestenapeo, a young Innu from the Côte-Nord region of Quebec, killed his abusive father in a fit of rage. He spent 10 years in prison. On his release, banished for life by his community, he headed for Montreal, where he soon joined a new community: that of the homeless Indigenous, the invisible among the invisible. Michel Jean works through this tragic world with grace, using a minimalist style, full of sounds, smells and images and devoid of pathos.”

Michel Jean (ed.), Wapke

Jean edited this collection of short stories by Indigenous writers—the first of its kind to come out of Quebec—with the title “wapke” (“tomorrow” in Atikamekw). The description reads, “Fourteen authors from multiple nations and backgrounds project themselves into the future through fiction, tackling current social, political and environmental themes. Under the direction of Michel Jean, Wapke offers an often striking social commentary in which the hope for change emerges.” Authors include Joséphine Bacon (Innue), Katia Bacon (Innue), Marie-Andrée Gill (Innue), Elisapie Isaac (Inuk), Michel Jean (Innu), Alyssa Jérôme (Innu), Natasha Kanapé Fontaine (Innu), J.D. Kurtness (Innu), Janis Ottawa (Atikamekw), Virginia Pésémapéo Bordeleau (Cree), Isabelle Picard (Wendat), Louis-Karl Picard-Sioui (Wendat), Jean Sioui (Wendat) and Cyndy Wylde (Anicinape and Atikamekw).

Ann-Helén Laestadius, Stolen (tr. Rachel Willson-Broyles)

Laestadius’s novel, an international bestseller, follows nine-year-old Elsa, an Indigenous Sámi girl who witnesses the poaching of a reindeer she was herding. She is threatened to silence by the hunter. The Kirkus Review explains, “Previous reindeer slaughters had gone unpursued by local police since this sort of crime against the Sámi (and their way of life) was considered mere theft. Frustrated by the seeming passivity with which the group accepts the situation, Elsa sets upon her own path as she grows into adulthood: She questions traditional gender roles as well as the failure of local police to apprehend the hunter who is torturing and killing her community’s reindeer…Willson-Broyles’ translation from Swedish is matter-of-fact and incorporates many phrases and words from the Sámi language.”

Joshua Whitehead, Making Love with the Land: Essays

So many exciting books in Moorhouse’s pile, and it ends with a bang. In general, nonfiction books from University of Minnesota Press push the boundaries in ways that are exciting. Whitehead is known for his award-winning novel Johnny Appleseed. Making Love with the Land, according to PW, “examines the relationship between queerness, the body, and language in his intimate first foray into nonfiction. Billy-Ray Belcourt says Making Love with the Land “is defiantly artful. The essays are alert to so much of the beauty and the terror of the world. I imagine they cost a great deal to write. While reading, I was entirely overcome with gratitude. How lucky we all are to witness Whitehead’s kinetic thinking as well to be in pain with him. A truly dazzling feat of heart, analysis, and sentence-making.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.