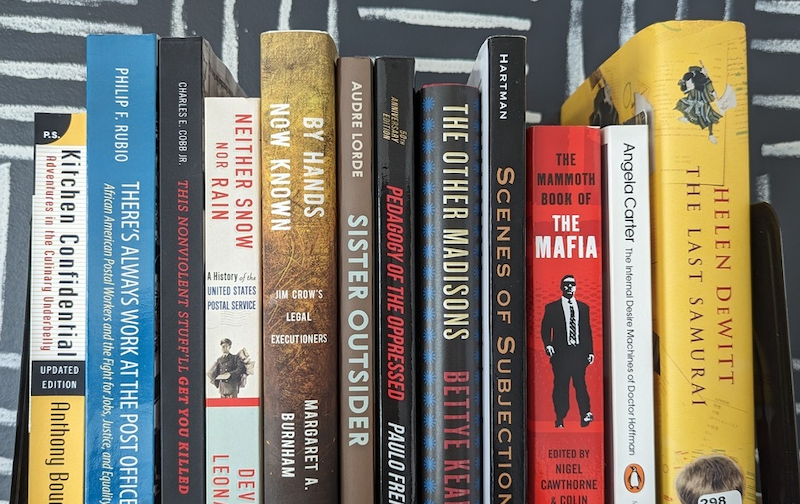

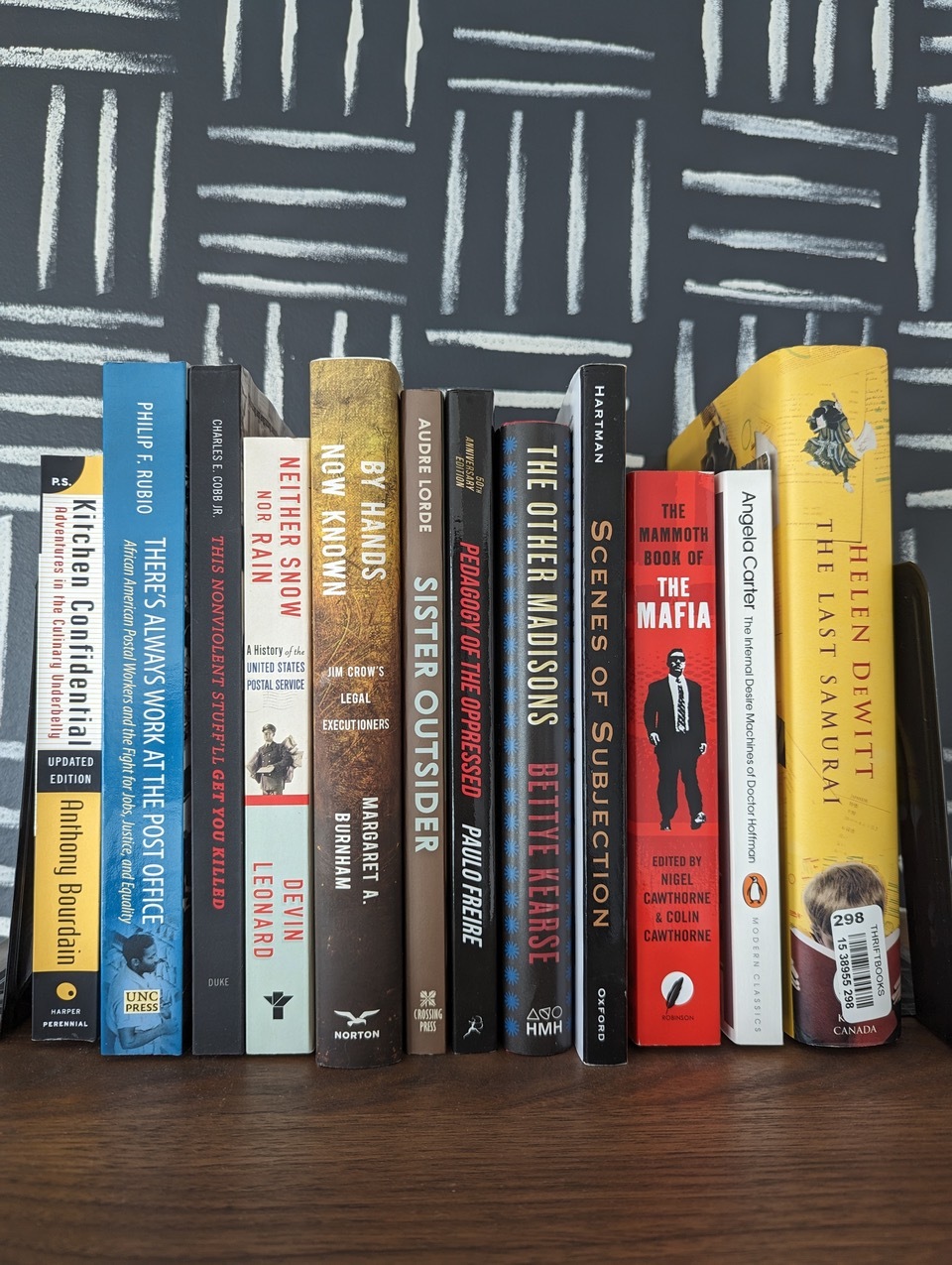

The Annotated Nightstand: What Stephen Kearse is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Anthony Bourdain, Angela Carter, Audre Lorde and More

The realities of Black Americans’ exposure to toxic chemicals is no secret, with their being 75% more likely than other racial groups to live near hazardous waste producers and sites in this country. It’s ironic (but, sadly, no surprise) that descendants of formerly enslaved people promised 40 acres and a mule through redlining, systemic oppression, and downright menacing often find themselves, in areas that can and do poison the people in their community. This one of the many terrible realities our country has created. (I do recommend reading the New York Times article about the poisoned Philadelphia neighborhood—whose members try to fight back).

Stephen Kearse’s second novel, Liquid Snakes, follows a few threads—but a toxic environment and its impact on Black lives is at its center. This becomes a larger metaphor for the reality of Black Americans and how racist culture in the United States often poisons them, slowly but surely. Kenny Bomar, a biochemist, likely lost a child, a stillborn daughter, due to local toxins. A grieving divorcée, his life seems to tip further and further sideways, as he develops a nefarious app (EightBall), designer drugs, and perhaps something even more terrifying. Meanwhile, two CDC investigators, Ebonee McCollum and Lauretta Vickers, are attempting to trace a death back to its origins—that of an overachiever at Harriet Tubman Leadership Academy. The student drank a fluid “so dark…[l]ight seemed to bend around it.” The result makes her disappear, and puts a dark liquid the investigators think has “gotta be industrial” in her place. Publishers Weekly calls Liquid Snakes “a dazzling pharmacological thriller that dances on the knife’s edge of satire…Written with incisive wit and studded with references to Black popular culture…and troubling incidents from recent history, this entertains even as it deeply disturbs.”

Regarding his to-read pile, Kearse tells us, “The theme is here is the basic now and next.”

Anthony Bourdain, Kitchen Confidential

Before Bourdain loomed large in the food writing (and tv) world, he wrote an essay for the New Yorker called “Don’t Eat Before Reading This.” Bourdain’s now-well-known storytelling and voice are immediate and undeniable enough to make it *out of the slush* (my god). An editor snapped him up, had him expand the essay into a memoir, and the rest is history. But what I didn’t know is that Bourdain had actually written two books prior to his meteoric rise—both in the uber-niche genre this reader has never experienced: “culinary mystery.” Bourdain had been writing for years, took a workshop with Gordon Lish, met a Random House editor, and published Bone in the Throat and Gone Bamboo. Both tanked. Kitchen Confidential was a NYT bestseller when it came out, and claimed that title again when Bourdain died in 2018.

Philip F. Rubio, There’s Always Work at the Post Office: African American Postal Workers and the Fight for Jobs, Justice, and Equality

One fact I think about a lot is that it became against the law to send postcards of terror lynchings in the US in 1908. (This is because of the Comstock Act—the same one that threatens abortion and contraceptive medication in the mail.) It feels noteworthy to mention it is not illegal to send these violent images in envelopes, which is a larger metaphor for the US and its engagement with racism. Rubio, himself a former postal worker, wrote a book about the intersection between Black postal workers and activism. The jacket copy states, “Black postal workers—often college-educated military veterans—fought their way into postal positions and unions and became a critical force for social change. They combined black labor protest and civic traditions to construct a civil rights unionism at the post office.”

Charles E. Cobb, Jr., This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible

The well-known leader of the Black Power movement Stokely Carmichael famously said of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s efforts, “His major assumption was that if you are nonviolent, if you suffer, your opponent will see your suffering and will be moved to change his heart. That’s very good. He only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none.” It’s surprisingly little-known how gun and gun rights played an enormous role in the Black Power movement, particularly in the efforts of the Black Panther Party, Huey P. Newton, as a law student, studied California gun laws in order to ensure BPP members could arm themselves so as to provide safety to their communities continually menaced by racists and/or police officers. One of the quickest legislative moves toward gun control, especially considering the bleak period we are in now defined, it seems, by mass shootings, was specifically targeting BPP members. The NRA even supported these gun restrictions. If you don’t know about the Mulford Act of 1967, you should.

Devin Leonard, Neither Snow Nor Rain: A History of the United States Postal Service

Whenever I see recurring topics in an author’s to-read pile it’s hard not to get a little excited. It makes me curious about what they’re working on next. And is Winifred Gallagher’s How the Post Office Created America (a book I’ve been wanting to read) going to be in here? (It’s not, but that’s okay! How much USPS reading can one do, really.) In the New York Times review, Lisa McGirr writes, “[Leonard] offers a host of interesting anecdotes, including one about an Idaho family who sent their child 75 miles by parcel post because it was cheaper than going by train…He devotes much of a chapter to Anthony Comstock, the longtime postal inspector and self-styled ‘weeder in God’s garden,’ who banned and prosecuted the mailing of birth control pamphlets, ‘marriage aids’ and ‘indecent’ literary works like Walt Whitman’s poems, lest they pollute public morals.”

Margaret A. Burnham, By Hands Now Known: Jim Crow’s Legal Executioners

This book was a finalist for the Kirkus Prize in Nonfiction as well as the LA Times Book Prize for History. It received starred reviews from PW, Kirkus, Booklist, Library Journal. While gatekeeping can be an annoying thing to contend with as a writer, with that much love showered on a single book it demands I sit up and pay attention. Living legend Angela Davis says By Hands Now Known “Needs to be read by everyone who recognizes the historic mandate of our time: to interrupt cycles of racist violence…But Burnham goes further, asking us to finally acknowledge the history of ever-present resistance, even under the most insurmountable conditions, and to consider what justice might mean today.”

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches

What new thing can I say about this ground-breaking book? Perhaps nothing—but I was shocked to hear Lorde took a pittance of a $100 advance because she felt she had to sign the contract quickly. I teach “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” the first day of every creative writing class I have if only to hear Lorde’s words said aloud as often as possible. Especially: “For within living structures defined by profit, by linear power, by institutional dehumanization, our feelings were not meant to survive. Kept around as unavoidable adjuncts or pleasant pastimes, our feelings were expected to kneel to thought as women were expected to kneel to men. But women have survived. As poets.”

Paulo Freire (tr. Myra Bergman Ramos), Pedagogy of the Oppressed

This book has, for many, created a paradigm shift for educators all over the world, inviting them to consider students as active agents in their own learning (rather than tabulae rasae awaiting knowledge). Apparently Pedagogy of the Oppressed is cited in the social sciences so frequently it holds the #3 spot for citations in that field. What blows my mind, however, is the linguistic journey this book took since Friere wrote it in while in exile in Chile, in Portuguese, between 1967 and 68. But it wasn’t originally published in Portuguese—instead, it was published in Spanish. Two years later, an English version came out. Two more years passed before it was published in Portugues in Portugal. But it didn’t reach Friere’s home country of Brazil until two years later.

Bettye Kearse, The Other Madisons: The Lost History of a President’s Black Family

I have no idea if the author of The Other Madisons and Stephen Kearse are related, but it would be extremely cool if two great authors were kin. In her book, Bettye Kearse traces her lineage in connection with the US President James Madison as well as to the Gold Coast, Madison’s plantation in Virginia, as well as archives and cemeteries. Kirkus Review says of this book, “ ‘Always remember—you’re a Madison. You come from African slaves and a president.’ So her mother told Kearse, who opens her account with invocations of the West African griot tradition of storytelling and oral history. That tradition found a place in slavery-era America because most slave owners did not allow enslaved people to learn to read and write. James Madison was different: He allowed his mixed-race son, Jim, to linger within hearing of education lessons.”

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America

As I said in my annotation for Anna Moschovakis’ TBR pile, Hartman’s first book is celebrating its twenty-fifth year of informing innumerable minds with a new edition. Since Scenes of Subjection was first published in 1997, Hartman’s impact on academic and non-academic readers alike is remarkable. Through thorough research and powerful writing, she illustrates the legacy of enslavement in the United States and that legacy’s reach far beyond emancipation. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes in the foreword published as a recent New Yorker article, “[If] we think of freedom as a right to move through life with genuine self-possession that can only be rooted in the satisfaction of basic human needs and desires, then Black emancipation in the United States was something altogether different.”

Roger Wilkes, The Mammoth Book of the Mafia: First-Hand Accounts of Life Inside the Mob, Nigel Cawthorne & Colin Cawthorne (eds.)

It’s hard to tell exactly how this book was done, but it seems Roger Wilkes interviewed over two dozen members of the mafia about their lives. The jacket copy reads, “Enter the underground world of organized crime. Get true accounts from the mouths of prominent former Mafiosi and others who have infiltrated the hidden world of organized crime: the American Mafia, the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, the Camorrah, ‘Ndrangheta, and Sacra Corona Unita. This fascinating compilation contains accounts from the likes of Richard Kuklinski, Frankie Saggio, Joey Black, Albert DeMeo, and Donnie Brasco.”

Angela Carter, The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman

This 1970s picaresque traces the impact of the titular doctor’s attack on an unnamed Latin American country. Hoffman’s “desire machines” allow visual illusions to fall within the gaze of the city’s inhabitants, quickly causing them to lose their minds. The protagonist, a government minister, however, is unfazed by these images. In the original review of the book in the New York Times, William Hjortsberg wrote, “[Angela Carter] builds the foundations of her myth out of hundreds of small observations. We soon forget that the terrain she observes with such care is the interior of her own imagination, for the world she describes becomes as real as any naturalist’s report…It doesn’t matter that none of this is real. The magic of fiction is that the only reality is what exists within the reader’s mind. If a thing seems to be then, for the purposes of fiction, it is. Taken from this perspective the boundaries of literature become limitless, the horizon extending as far as a writer’s imagination will carry him.”

Helen DeWitt, The Last Samurai

Here I thought I was going to learn early-aughts Tom Cruise movie of the same name was originally a novel, but no. And, actually, this was part of DeWitt’s frustration, one would think, with publication of this book. The novel follows a single mother and her son, the latter being a prodigy polyglot. His mother perpetually puts on Akira Kurosawa’s masterpiece (yes, I am a Kurosawa stan) The Seven Samurai, which the child soon knows by heart. DeWitt originally wanted to call the book The Seventh Samurai, in reference to Kurosawa, but the publisher couldn’t get the rights. So The Last Samurai it was—and then the movie of the same name came out two years later! While the book The Last Samurai got glowing reviews, it went out of print for years. New Directions put it back out in 2016, and it’s having what seems to be a well-deserved renaissance.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.