The Annotated Nightstand: What Anna Moschovakis is Reading Now and Next

Books by Saidiya Hartman, Annie Ernaux, Jenny Diski, and more

Anna Moschovakis is one of those unicorns in the literary world who manages not only to do it all, but do it well—more than well. She is a poet, translator, novelist, critic, publisher, professor, and community organizer. Her translation from French of David Diop’s At Night All Blood Is Black won the 2020 Booker Prize. Her poetry collection You and Three Others Are Approaching a Lake won the James Laughlin Award from the Academy of American Poets. She helped found the small press darling Ugly Duckling Presse, prized for its translations, experimental works, and beautiful letter-pressed covers.

And, more recently, Moschovakis cofounded a collectively run art space Bushel in the Catskills. It is clear she has invested years of time and energy in connecting people and to people through her activism, translation, and writing. On the other side of reading of her accomplishments, one largely wonders what it is she can’t do.

Moschovakis’ first novel Eleanor, or, the Rejection of the Progress of Love was a meta-novel that jockeys between the novelist, the titular character she was writing about, and the novelist’s fuzzily defined relationship with a critic. Overall, it is a funny, philosophical novel that employs plot only when necessary. This allows Moschovakis to drill down into the concerns of creative production, moving away from one’s youth, and what it is, essentially, to “be.”

And, now, we have her second novel, Participation, recently put out by her publisher—unless she’s translating—Coffee House. Participation follows E and her membership in two reading groups, Love and Anti-Love, the different ways they (and life) tug at her. Through the reading group texts (Aristophanes, Badiou), E’s memories of her relationships with people, along with the backdrop of news we know all too well—environmental disaster, white supremacy—Moschovakis employs her intellect with a level of vigor we see less often than we should. In its starred review for Participation, Publishers Weekly states, “Throughout, Moschovakis brings her fierce intelligence to bear in the structurally surprising and impeccably executed narrative. This is formal innovation at its finest.”

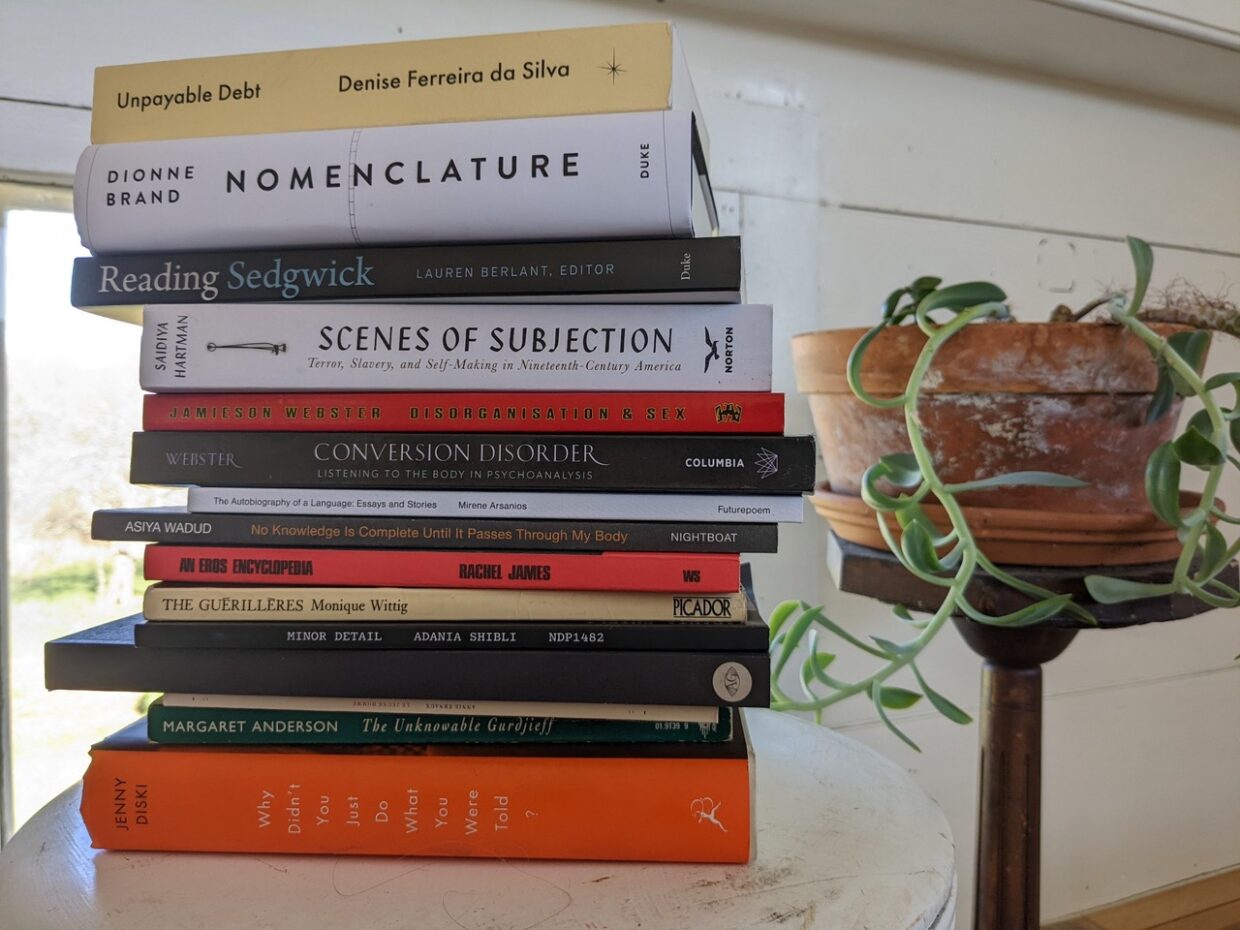

Anna tells us about her to-read pile:

“My life is split between two places right now, which means my book stacks are split and which has also slowed down my reading even more than usual (I’m always slow and like to keep some books nearby for years before quite finishing them). This stack includes a book I’m ostensibly reading with others though I keep missing the group meetings; two books that re-read, re-issue or reframe previous work that is already important to me—something I’ve become interested in, partly as a way of checking my own anxiety about staying ‘up-to-date’; two books by one author whose psychoanalytic writing feels like an X-ray of my brain (and who is helping me finally approach reading Lacan); some new and newish poetry books by friends or from presses I subscribe to or follow; one book of the ‘lingering’ category that I am more than three years delayed sending to the person I promised it to (I will send it today!); another lingering book I just can’t stop revisiting, like a language-magnet; a recent-ish issue of an indispensable labor-of-love feminist film journal; a tiny French book that a few months ago was borrowed by my seat-mate on a plane, read in full, and silently returned to me, an experience I have never before had; a compulsive research read; and a posthumous collection by someone I’ve heard of for years and felt sure I’d love, and do.”

Denise Ferreira da Silva, Unpayable Debt

Octavia Butler’s Kindred is a what the author described as a fantasy novel—one in which a Black woman in 1976 Los Angeles is transported through time to antebellum Maryland where she becomes increasingly entangled with a violent and complicated white ancestor and owner of her enslaved Black ancestors. With this novel a flashpoint to begin her investigations, Da Silva considers how concepts of capital are so insidious they inflects everything from laws to ethics, not to mention the ways in which we feel free to exploit others.

Dionne Brand, Nomenclature: New and Collected Poems

The imitable Dionne Brand’s latest collection came out just this October. In an endlessly quotable interview with David Naimon, which you can read or listen to, Brand states: “You will notice in Nomenclature for the Time Being, the language of chemistry is used or the language of advertising is used because I think we live those languages and we hear them. We hear the word propylene, we hear those things. But some of our poets are somehow required not to hear those words or to think those words outside of our vocabulary, but in fact we are living the word, we are living oil all the time. For me today, oil is like slavery, the slave trade worked the last five centuries or whatever and oil worked this next one or two that we’ve just lived, and the destruction of the planet, the consuming of the planet inside of itself, the burning of the planet. So we must use this language because we are living this language and we would be delusional or we are being delusional not to use this language, to admit who we are.”

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America

Hartman’s first book is celebrating its twenty-fifth year of informing innumerable minds with a new edition. Since Scenes of Subjection was first published in 1997, Hartman’s impact on academic and non-academic readers alike is remarkable. Through thorough research and powerful writing, she illustrates the legacy of enslavement in the United States and that legacy’s reach far beyond emancipation. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor writes in the foreword published as a recent New Yorker article, “[If] we think of freedom as a right to move through life with genuine self-possession that can only be rooted in the satisfaction of basic human needs and desires, then Black emancipation in the United States was something altogether different.”

Jamieson Webster, Disorganization & Sex; Conversion Disorder

“What was I like as a patient?” psychoanalyst Jamieson Webster asks an interviewer. “My first analyst was really tough. I went to see him when I was nineteen. He tolerated a lot. Sometimes I’d bring friends to wait for me, they’d be talking in the hallways while I was in session. I brought a dog once. She was a puppy. She peed all over his office. That’s not the worst of it. That’s the edited version.” Webster has penned a few books (beyond these two, The Life and Death of Psychoanalysis), and is an analyst practicing in New York City, while also contributing to Artforum and New York Review of Books.

Mirene Arsanios, The Autobiography of a Language: Essays and Stories

I had come across Arsanios’ wonderful work in her 2020 pamphlet Notes on Mother Tongues: Colonialism, Class, and Giving What You Don’t Have. It seems this “fictional essay” is in her new collection of prose. Mónica de la Torre says of The Autobiography of Language, “Here the mirror image of the almost hallucinatory, heart-rending loss of the familiar is literary defamiliarization. Arsanios both mourns and blasts apart the notion of the mother tongue, reminding us that for each ‘mother tongue’ at least another tongue is silenced. Desire propels her genre-defying writing, which grief notwithstanding still manages to tongue languages, and that is her genius.”

Asiya Wadud, No Knowledge Is Complete Until It Passes Through My Body

The Congolese dancer and choreographer Faustin Linyekula provides Wadud’s book title, and she employs the multimodal works of Okwui Okpokwasili throughout the collection. This is all germane, considering the content focuses on the body’s capacities despite—or because of—stress. “This poetry is filled with incantatory language and startling details,” says Evie Shockley of Wadud’s book. “[I]t ranges through history and the natural world, composing a compelling metaphysics of black diasporic womanhood.”

Rachel James, An Eros Encyclopedia

It feels apt to quote another person in Moschovakis’ list, as she praises James’ hybrid collection. Jamieson Webster says of An Eros Encyclopedia, “Psychoanalysis said Eros was a mischief maker, an ancient child playing hide and seek, where the pleasure of language for language’s sake is the most pure stakes of the game. Come read the luminous incantation that is Rachel James’s An Eros Encyclopedia and remember: ‘You are an acceptable chaos discipline, God of provocation and humor, You are an explosively elegant being.’”

Monique Wittig, Les Guérillères (trans. David Le Vay)

The feminist thinker’s 1969 novel is one that continues to be read and adored. The original translation into English was reviewed in the New York Times in 1971. In her review, Sally Beauman synthesizes the feminist thinker’s novel thusly: “Her women are les guérillères, a strange, fierce warrior tribe. They live in fortified camps; they fight with knives, rifles, machine guns, rocket launchers. They worship the sun‐goddess, the circle, the vulva. They trace their descent from Boadicea, Penthesilia, Hippolyta, the Amazons. They have rites in which they anoint their bodies, sing sacred chants, drink wine. They taste drugs and spend the night orgiastically in each other’s arms. For food, they kill animals. For fun (and for survival) they kill men.”

Adania Shibli, Minor Detail (trans. Elisabeth Jaquette)

Shibli’s novel in Jaquette’s translation was a finalist for the National Book Award and longlisted for the Booker Prize. The narrative is bifurcated, beginning in 1949—just after the 1948 Nakba (aka Palestinian Catastrophe), in which continual strife and violence left 700,000 Palestinians fleeing for their lives and/or exiled from their land. This portion follows Israeli soldiers who locate a Palestinian girl among a group of Bedouin people. After they murder the Bedouins, the soldiers proceed to violate the girl her before murdering her, too. For the second potion of the novel, as the jacket copy states, “Many years later, in the near-present day, a young woman in Ramallah tries to uncover some of the details surrounding this particular rape and murder, and becomes fascinated to the point of obsession, not only because of the nature of the crime, but because it was committed exactly twenty-five years to the day before she was born.”

Another Gaze: A Feminist Film Journal Issue 4

The ethos for Another Gaze is, according to them, “to provide nuanced criticism about women and queers as filmmakers, protagonists and spectators.” The particular issue in Moschovakis’ pile contains: “essays about Madeline Anderson, Lorenza Mazzetti, Laure Prouvost, Ben Rivers & Anocha Suwichakornpong, Agnieszka Holland’s Spoor, Susan Sontag’s filmmaking career, Storm De Hirsch, Zia Anger, Ashley Connor, Bruce LaBruce, Pina Bausch/Chantal Akerman, Magdalena Montezuma, Rebecca Horn, Anne Charlotte Robertson, Zhu Shengze, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Maya Da-Rin, Camila Freitas, Gong Li An in-depth Afro-Brazilian roundtable with Tatiana Carvalho Costa, Janaina Oliveira, Everlane Moraes and Kênia Freitas; sections on Kira Muratova and Anne Charlotte Robertson; essays on subtitles, diffractive cinemas, ecocriticism/the anthropocene, literary adaptations, intimacy coordinators, strike on film, representing the internet. Interviews with Betzy Bromberg, Zia Anger & Ashley Connor, Brett Story, Amandine Gay, Andrea Luka Zimmerman & Therese Henningsen. Experimental criticism from Kathryn Scanlan, Jen Calleja and Elissa Suh.”

Annie Ernaux, Le Jeune Homme

The winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize in Literature perhaps needs little introduction. Known not only for her excellent literature but also her activism, Ernaux quickly employed the platform the Nobel win provided to express her support for the women-led uprisings in Iran. The book (recently published and as-yet untranslated from French into English), considers Ernaux’s love affair with a man decades her junior years ago—and the complications of power the relationship put before her. The Nobel Committee’s explains Ernaux earned the prestigious prize “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.”

Margaret Anderson, The Unknowable Gurdjieff

This book charts the work of the Armenian/Greek occultist George Gurdjieff who born and raised in the extended Russian empire in the late 1800s. He is largely known for cultivating the “Fourth Way,” which attempted to amalgamate faith practices from those Gurdjieff witnessed while traveling for several years through Central Asia, Iran, Egypt, India, Tibet, and Rome. Gurdjieff thus combined the approaches to of the yogis, fakirs, and monks he encountered to create “the Work” (as Gurdjieff’s acolytes called it). Gurdjieff defined humanity’s experience when moving through the world as “he waking sleep,” with his approach to life as a means to access higher consciousness. The entirety of Gurdjieff’s Wikipedia page is a pretty wild ride with an endless barrage of famous names popping up—I highly recommend giving at least that a read.

Eve Sedgwick, Reading Sedgwick (ed. Lauren Berlant)

Moschovakis tells us: “this is one of the ‘re-reading / reframing books,’ but it’s out of order in the stack.” The iconic queer theorist has an deserves an endless list of who’s-who writing about their encounters with her work. This anthology includes words from Lauren Berlant, Judith Butler, Lee Edelman, Ramzi Fawaz, José Esteban Muñoz, and many others. Christina Crosby said of the collection, “Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s writing remains indispensable, never more so than now when the light of her intelligence illuminates a darkening horizon. We need her intelligence, her queer sensibility, and her way with words.”

Jenny Diski, Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told?: Essays

This book is a collection of the late Diski’s essays as published in the London Review of Books in which she writes on everything from reviews of Roald Dahl’s biography to her own cancer diagnosis. Kate Kellaway in her review in The Guardian gives us a sense of Diski’s iconoclastic impulses. She states, “Diski was worth hiring on any subject: feed her base metal, she turned it into gold. When not writing about herself, she is at her best considering the nasty and/or nondescript. Her subjects include Jeffrey Dahmer, Howard Hughes and Richard Branson, and she does not let Christine Keeler get away with a stuffy, faux-respectable take on her past… She is the most undeceived of writers—and surprising.”