The Annotated Nightstand: What Shane McCrae Is Reading Now and Next

Featuing Ama Codjoe, Renee Gladman, William Empson, and More

Ever since someone put a copy of Shane McCrae’s Blood in my hands I haven’t been able to look away from his poetry. Really since McCrae’s first book Mule in 2011 he has been putting out another collection of poems at a whiplash-inducing clip of about one a year. As with Mule and Blood, he continues to turn over concerns that defined so much of his life and, thus, our own as members of the same society. This includes (but is not limited to): crises of faith, internalized racism, the legacy of enslavement, sexual violence. We can read of his experiences of growing up biracial in his racist grandparents’ home, poems from the perspective of Jefferson Davis’ mixed-race adopted son, the events of the Old Testament.

McCrae’s first full-length book of nonfiction, Pulling the Chariot of the Sun: A Memoir of a Kidnapping, attends to the former series of experiences in that list—his white racist maternal grandparents stealing McCrae away from his Black father by the time McCrae was three. His abusive grandparents threatening his white mother with disappearing into Mexico with McCrae if she revealed their whereabouts to McCrae’s father.

The refrain of “Am I misremembering it?” in the early pages of this memoir has a dread-inducing valence considering how McCrae’s grandparents withheld or shared information depending on how it served their desire to keep McCrae from his Black father and instill a sense of hatred for his Black relatives and identity. He writes, “[N]obody mentions my father to me except to tell me he didn’t want me, but that’s OK because he’s black, and I shouldn’t want him right back. I grow up screaming I don’t want him right back.”

As with so much of McCrae’s writing, the descriptions of his personal experiences speak to the larger systemic violences and how they, insidiously, make their way into the one’s life. Why, for example, didn’t his father go to the police? Years later, well after his grandparents are dead, McCrae’s father “explained why he hadn’t asked the police for help finding me, which was for the same reason he couldn’t ask the police for help with anything else.”

McCrae’s work as a poet shines through in this work, with brief lyrical vignettes give way to meta-considerations of the memoir’s topic (kidnapping, memory) and chronological leaps. He’s not afraid of the breathlessness of a run-on sentence, the power of image-charged metaphors. This memoir’s consistent movement and shiftings, not to mention McCrae’s potent language, kept me rapt.

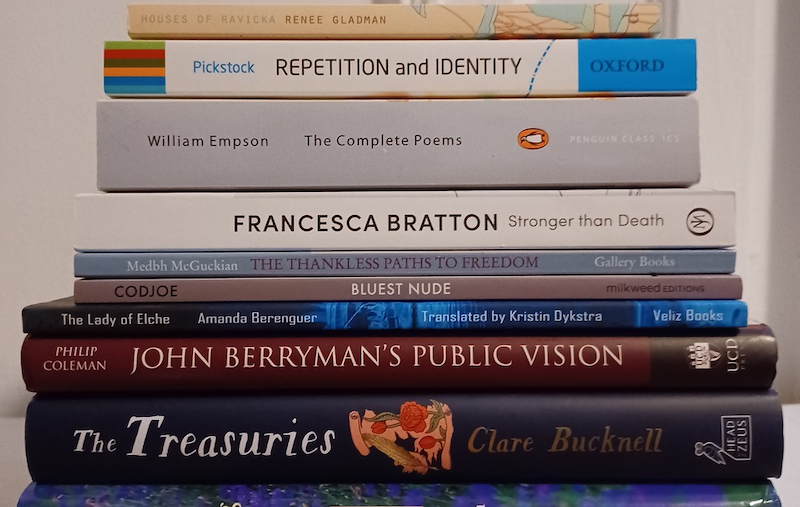

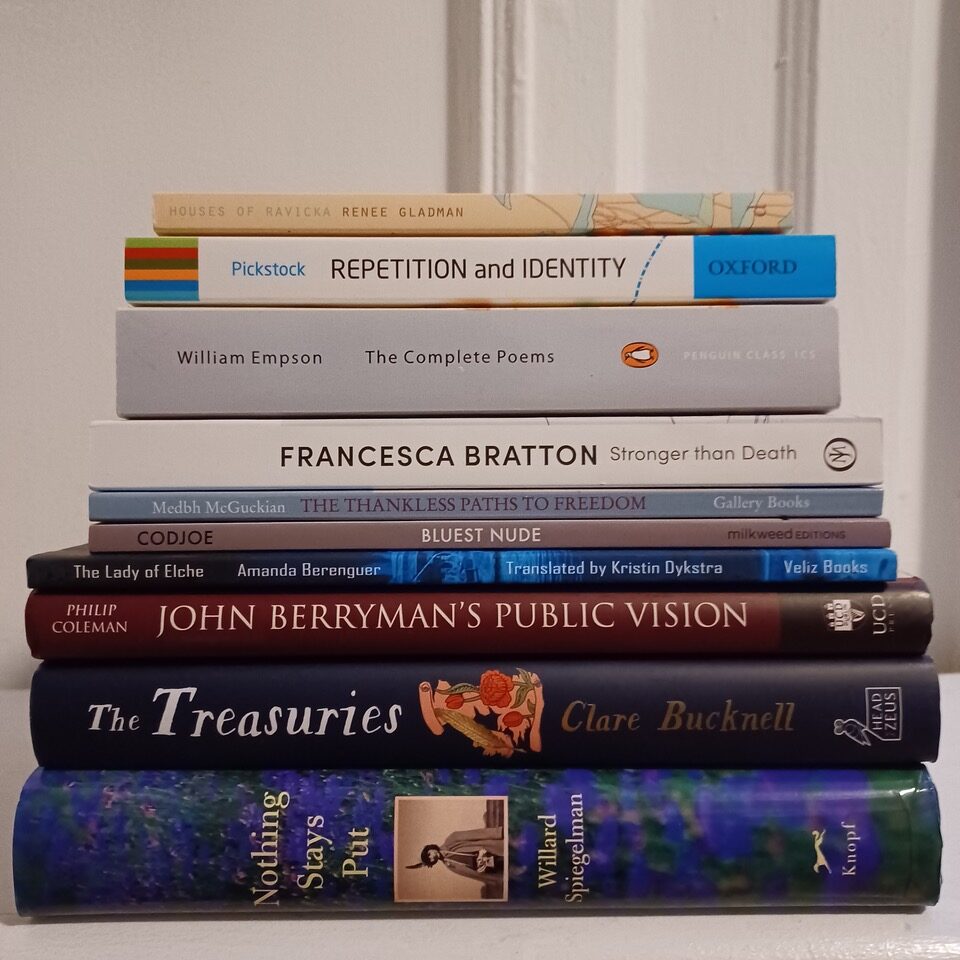

Regarding his to-read pile, McCrae (generously) shares the following:

As you can see, every one of these books is either by a poet (yes, Catherine Pickstock writes poems—quite good poems, actually, and I wish she would collect them), or about a poet (or poets, as in the case of The Treasuries). Here’s why I chose the books: Houses of Ravicka because Gladman is one of my favorite living writers; Repetition and Identity because Pickstock is one of my favorite thinkers about God; Empson’s Complete Poems because the book is more notes than poems, and because the poems themselves are wonderful, some of the best poems of the 20th century; Stronger Than Death because Bratton is a brilliant writer on Hart Crane; The Thankless Paths to Freedom because it includes “Poem on the Landscape Behind the Mona Lisa,” the poem I’ve most loved this year; Bluest Nude because Codjoe is an exciting poet; The Lady of Elche because the little bit I’ve so far read of it struck me as revelatory; John Berryman’s Public Vision because I love Berryman’s work and I’m working on a thing; The Treasuries because its subject, the influence of poetry anthologies on British culture, is fascinating; Nothing Stays Put because Amy Clampitt’s poems are so, so good and everyone ought to read them.

*

Renee Gladman, Houses of Ravicka

Houses of Ravicka is the fourth installment of poet and novelist Renee Gladman’s fantastical series set in the city-state of that name. If you’ve read Calamities or Prose Architectures (nonfiction and visual work, respectively), Ravicka lives in these collections too.

In Phoebe Clark’s review at The White Review, she writes,

Little can prepare you for the experience of reading Renee Gladman’s Ravickian quartet and encountering the oddity, humour, and singular intelligence of her mind….[T]hese novels remind me of little else I have encountered in contemporary literature. Ravicka has textual predecessors—Gladman overtly nods to Samuel Beckett, Anne Carson, and Julio Cortázar—but immersion in Ravicka feels, somehow, more like watching contemporary dance or experimental film than reading a novel. Absurdity abounds, non-sequitur is employed liberally, and syntax seems more significant than setting or plot. Nonetheless—and herein lies Gladman’s achievement—these novels are provocative and profound.

Catherine Pickstock, Repetition and Identity: The Literary Agenda

I appreciate how this undeniably heady work has bullet points about what it contains, including: “A new linking of recapitulation and restoration in the Church Fathers to repetition, along with a related account of the relationship of the formation of orthodoxy and Gnosticism.” Pickstock also expands on Kiekergaard’s notion of “repetition.”

The jacket copy states, “The category of ‘the literary’ has always been contentious. What is clear, however, is how increasingly it is dismissed or is unrecognized as a way of thinking or an arena for thought. It is skeptically challenged from within, for example, by the sometimes rival claims of cultural history, contextualized explanation, or media studies.”

William Empson, The Complete Poems

Empson was a bit of a wunderkind as a critic, writing Seven Types of Ambiguity when he was twenty-one at Cambridge in the 1920s—a work that has its own Wikipedia page, as it is a foundational text for New Criticism. He clearly had a compelling life that involved living and teaching in China for amounts of time, teaching at Kent State at the same time as Robert Lowell and Delmore Schwartz, being knighted.

The thing that most compels me, however, is how his scholarship was revoked from Cambridge and he was even expelled from the school. The cause? His “bedmaker” (a kind of collegiate servant of the time) discovered condoms in his nightstand. For this terrible infraction, Empson not only was expelled, but banished from Cambridge entirely!

Fifty years later, after a slew of accolades and accomplishments, his college awarded him an honorary degree the same year he was knighted. May we all have such epic years as Empson at the age of sixty-three.

Francesca Bratton, Stronger than Death: Hart Crane’s Last Year in Mexico

The poet Hart Crane, the center of Bratton’s hybrid work, is largely known for his long poem The Bridge—a kind of hopeful response to Eliot’s The Wasteland. He was inspired by life in Manhattan after ditching his small town in Ohio. (A wild sidenote: his dad invented Life Savers candy.)

Unfortunately, as a gay man in the 1920s, even New York wasn’t big enough to spare him. Mental illness and alcohol abuse plagued Crane, especially after The Bridge was panned. He got a Guggenheim to live and work in Mexico, and never made it back.

As the jacket copy of Stronger than Death explains, “Bratton tracks Hart’s year among the vibrant artistic and political communities of Mexico City. His story is interwoven with that of his mother [Grace Crane], exploring Grace’s lifelong frustrated creativity and, after [Crane’s] death, debilitating grief. Finally the book explores Hart’s legacy as a queer man and as a poet, informed by Francesca’s responses to his work during her own periods of struggling with mental illness.”

Medbh McGuckian, The Thankless Paths to Freedom

Seán Hewitt’s review of McGuckian’s most recent collection in The Irish Times states,

As with all of McGuckian’s intricate work, there is real texture to the form of these poems—a propulsive alliteration, an attention to internal rhyme, to rhythm – that allows the poems to flow and communicate a sense beyond literal meaning. They become, also, vehicles of affect, of sensation, of music. “Time’s hand / touching, after time has flown, hangs the dated / death by a blue heavenly, a reckless / blossoming.” Present, too, are crystalline images that hint at the political, at social change, without ever fully giving up their secrets. This is a glinting and ornamented world that slips in and out of the real and the dream, the past and the present, delivering its message through the subconscious, though hinting always at real critique. The curve of the streets, in the poem Star Patient, for example, is “like a jewel box tormenting / the altar steps.”

Ama Codjoe, The Bluest Nude

Codjoe’s latest poetry collection is also in my to-read pile—and it’ll be in yours too once you read/listen to the interview she did with David Naimon on Between the Covers. She talks about many things, including how Lorraine O’Grady’s essay “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity” inspired her and the book.

She tells Naimon,

[W]hat do I see when I look at myself and my naked body in the mirror? And even alone, am I ever alone? I guess it’s about what are the things that are shaping my sight and what have I internalized, how can I use my eyes, in a way that’s a tool, and then even when I’m looking at myself, am I also seeing myself as other people see me? It just feels like a hall of mirrors really and this intimate space of a bedroom and/or a hotel and a lover like who else is in the space with us? I think that one of the many centers of the book is these unanswerable questions because there’s something about the feeling or idea of nakedness that is about stripping bare and yet there are so many layers left even on that naked flesh and particularly thinking about that as a racialized body.

Amanda Berenguer, The Lady of Elche (trans. Kristin Dykstra)

Berenguer was a Uruguayan poet and member of the Generación del 45/Generation ’45, named as such because their careers took off around that year. They had enormous influence on the literary world in Uruguay. The sculpture of Berenguer’s title, Lady of Elche, is incredible to look at, and a rich text. An Iberian bust from the fourth century B. C. E. She has enormous coils around her ears that look like massive wheels, and apparently was used as an urn. (Apparently she even made an appearance in a recent Thor movie.)

Edwin Torres says of this collection, “Over the course of these pages, in a mounting inevitability of humanity, Berenguer positions the embodied self as a new self—a ravenous becoming towards a breathless forage into the temporal, ‘a limitless birthing between silence and voice.’ Kristin Dykstra’s sensuous translation reveals an essential prophecy of ownership within witness and cadence.”

Philip Coleman, John Berryman’s Public Vision: Relocating the Scene of Disorder

John Berryman strikes, at best, a complicated figure for his racially charged imagery (Tyehimba Jess breaks it down powerfully in this interview), but he is also one who looms large in American literature as one who did a great deal in a confessional mode along with the accolades he received. The cover of Coleman’s book surprised me, as it has a young, clean-shaven Berryman looking directly at the camera. The only images I had seen of the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet where later, when he bore a notably enormous beard with shocks of white in it.

The thing that bewilders me when looking at Berryman’s biography is how frequently his mother changed her name, or used a different name. Her birth name was Martha, but she went by Peggy (usually short for Margaret). After she remarried, she began going by Jill—and this after marrying a man who had the same name as Berryman’s father and Berryman himself (who was John, Jr.). Swirling eyes emoji, etc.

Clare Bucknell, The Treasuries: Poetry Anthologies and the Making of British Culture

A really compelling-sounding book regarding the impact of anthologies of poetry.

The jacket copy reads,

From the court of King Charles II to the Mersey Sound, this surprising, definitive history reveals the poetry anthology to have had a pivotal effect on the course of British culture over the centuries…[A]nthologies aren’t just part of literary history. Over the centuries, they have shaped British society and culture, creating new reading publics and generating conversations around politics, national identity, morality, class, gender and sex. The Treasuries, by the literary scholar and journalist Clare Bucknell, is the story of the poetry anthology in English: an accessible social history that explores the impact of a handful of widely read books across four centuries.

Willard Spiegelman, Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt

Amy Clampitt, the focus of this biography, is something those of us who haven’t accumulated accolades with enormous cultural capital can look to as a guide for one who didn’t hit those marks when young. That said, she was someone who has some notable accomplishments at the beginning of her career. After living in New York City for about twenty years, once she was in her forties, Clampitt started writing poetry. She published her first poem at the age of fifty-eight—in the New Yorker. She was sixty-three when her first full-length book of poems came out with Knopf. She got a Guggenheim at sixty-two, a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship at seventy-two (!).

Sigrid Nunes says of this book, “What joy: hours and hours in the thrilling company of the extraordinarily gifted, large-souled, inspiring poet Amy Clampitt—thanks to her superb and devoted biographer. Willard Spiegelman’s Nothing Stays Put is a triumph of literary scholarship and imagination.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.