The Annotated Nightstand: What Rachel Zucker is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Mary Ruefle, Nicole Sealey, Joy Harjo, and More

During the often-dread-inducing/dreadful time of year when publications are putting out there “best of the year” lists, I’m glad to shine a light on a book I loved and deserved more attention than it seemed to receive. This is always a hard task, especially for small press books. I would have loved to see the to-read piles of these authors and written about their books: Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s Negative Money, Brandon Shimoda’s Hydra Medusa, Azo Vauguy’s Zakwato & Loglêdou’s Peril (tr. Todd Fredson), Amanda Montei’s Touched Out: Motherhood, Misogyny, Consent, and Control, Daphne Kalotay’s The Archivists: Stories.

I’m happy to have an opportunity to write about the poet Rachel Zucker’s The Poetics of Wrongness, a series of pieces she wrote as a Bagley Wright Lecturer in 2016 and was published by Wave Books this year as well as selected prose. Lectures are a relatively ancient form (dating to medieval times at least), and one we associate with instruction—a person with intellectual authority imparting their genius on their audience in a way that might change them.

For someone like Zucker for whom taking up power isn’t a comfortable experience, this wasn’t an easy task. At one point in The Poetics of Wrongness she writes, “In order to write [poetry] ethically… I need to think about who I am as maker and what I gain by my writing—understanding, money, notoriety, pleasure, power?” In her podcast Commonplace, Zucker spoke with fellow poet and Bagley Wright Lecturer Douglas Kearney (who won the Pegasus Award for Poetry Criticism for his own amazing published lectures Optic Subwoof!) about many things—including their experiences writing lectures on craft. For Zucker, it was deeply fraught.

At one point, she tells Kearney, “Part of my drama was about authority. For sure, that comes from being a woman, being an only child, coming out of a very patriarchal religion, coming out of a heterosexual marriage, having only male children, having a male editor—wanting to prove myself and get the gold ring. At the same time I knew that my deepest most authentic work in life was about trying—you know, I can’t live outside of capitalism, but can I, instead of going after this power that I think will protect me or, I dunno, make me a man! Can I dismantle this within myself—the need for it, the addiction to it, the desire for it—and still speak?”

These inquiries are emblematic of Zucker’s approach to writing—she will point directly to the part of herself most would do much to hide from themselves and, failing that, likely the world. The rigor and expansiveness of her lectures and prose surprised me again and again. The ways in which she adheres to lectures in the format we know and generally accept—and then pushes back, breaks, flees from it. The vulnerability of the process and her thinking throughout was radically generous.

In her lectures and prose pieces (“An Anatomy of the Long Poem,” “Why She Could Not Write a Lecture on the Poetics of Motherhood”), she references poets from past and present while simultaneously interrogating her experiences as a poet and person. Throughout, Zucker interrogates what “confessional” means, writing about yourself entails, what one’s limits should be (or not). These pieces stirred up so much inside me regarding power, the lecture form, writing, teaching, feminism, the ethics of writing about the self and those in your life. Anyone who is touched by these concerns should read Zucker’s work in all its forms.

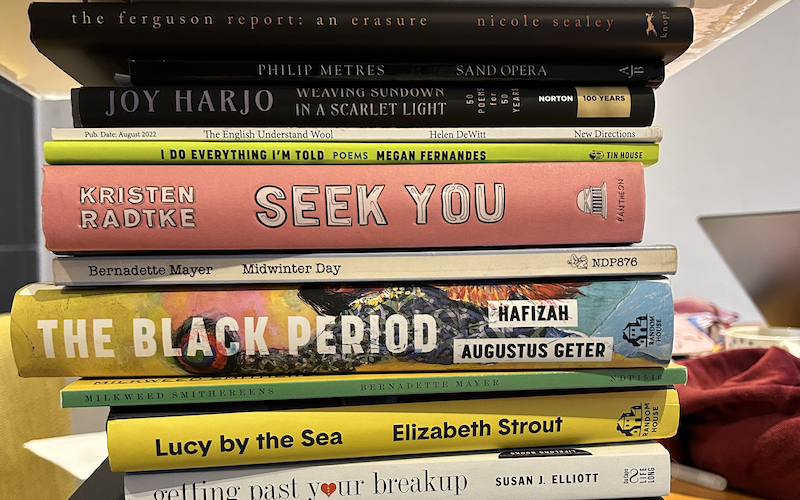

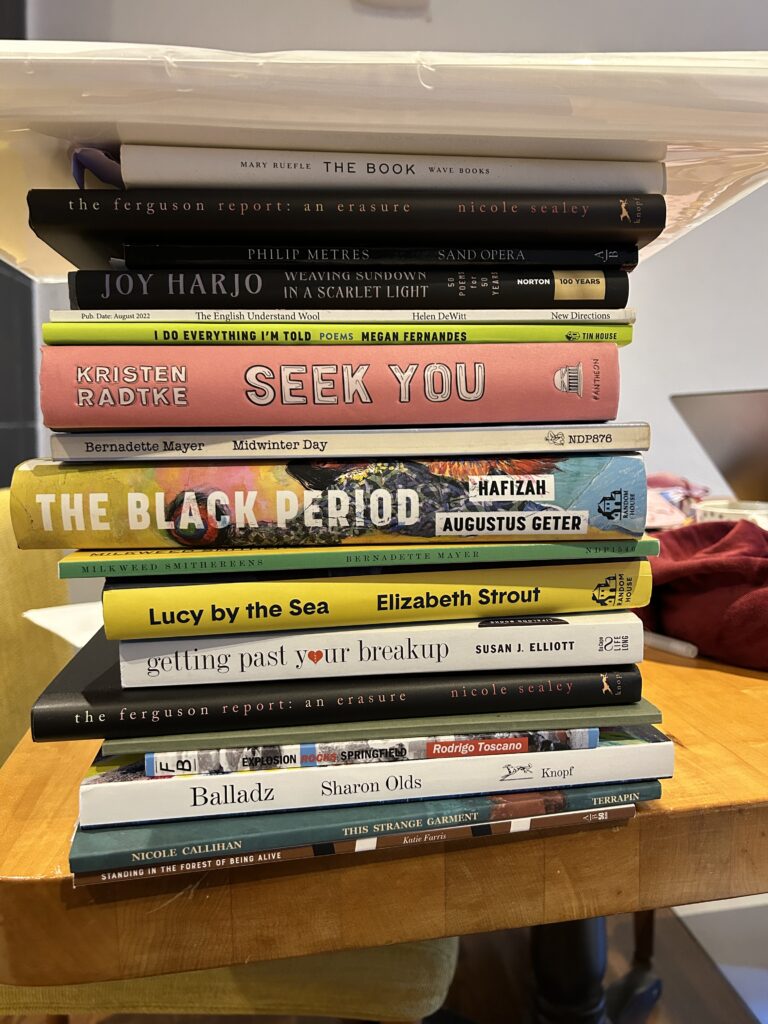

Zucker tells us about her to-read pile, “My real to-read pile is actually many piles (all over the house) and includes pdfs books in a folder on my computer called ‘Books to Consider’ (I’m currently reading a pdf of Tanya by Brenda Shaughnessey) and audio files of books and lectures I’m listening to (recently finished Smile at Fear by Pema Chodron, Also A Poet by Ada Calhoun) or am about to listen to (Fully Alive by Pema Chodron). The pictured pile contains an unpublished manuscript by my father, Benjamin Zucker, several books I’m reading with a group as part of ‘Reading with Rachel,’ a live-virtual book group, books I’m reading but haven’t finished, books I haven’t started yet and a few that I’m re-reading.”

Mary Ruefle, The Book

Every time Ruefle puts out another book it’s hard not to get excited. I recommend watching her reading with Rae Armantrout. If you want a real treat in less than 5 minutes, one of the most amazing portions is an old letter she found and from which she read aloud—a wild mind-dump on anxiety surrounding gift giving. Publishers Weekly says of The Book, “The generic title of this beguiling compendium of prose from poet Ruefle (Dunce) belies the richness and variety within. The fragmentary entries touch on an eclectic array of topics and range in length from a few lines to several pages, but they all demonstrate a poet’s eye for brevity and language. The title piece celebrates the intimacy of reading books that feel as if they were ‘written especially for me.’ In ‘The Photograph,’ Ruefle describes a photo of an anonymous ancestor of hers from unknown generations past and rhapsodizes about the bond that photos enable between viewer and subject. Ruefle turns from amusement to melancholy on a dime, best exemplified in ‘The Perk,’ in which the author describes throwing her 50-year-old husband a ‘child’s birthday party,’ complete with a clown who later, after losing his job as an entertainer and trying to kill himself, turns up at the hospital where her husband, a doctor, works.”

Nicole Sealey, The Ferguson Report: An Erasure

Kevin Young writes of Sealey’s work in the New Yorker: “Nicole Sealey’s breathtaking sequence ‘The Ferguson Report: An Erasure’ reimagines the Department of Justice’s investigation of the Ferguson Police Department following the tragic and galvanizing events that occurred in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Redacting the report line by line, word by word, letter by letter, Sealey excavates larger and deeper insights from its account of systemic racism and violence. These are declarations of a different sort, telling a tale, if not of two cities—Ferguson and St. Louis—then of what can feel like two nations. Sealey identifies a ‘they’ and a ‘we,’ divided along lines of power: ‘They say stand in line, / so we stand in line.’ Obedience, conflict, contradiction: all lead to the kinds of conflagrations that Ferguson saw in response to the killing of the unarmed teen-ager Michael Brown by a police officer who saw Brown’s very body as a weapon…‘There’s a pause between wails / in which you hear your shut / eyes dilate,’ Sealey’s transformed poem declares. ‘The Ferguson Report: An Erasure’ at once illuminates truths of our fraught time and seeks radical possibilities within all-too-familiar narratives. As the poem implores us: ‘Listen.’”

Philip Metres, Sand Opera

“Philip Metres’s poetry collection Sand Opera is complex, an untamable polyvocal array of clipped narratives in post-9/11 (if we are to believe such historical markers) America,” writes Solmaz Sharif in The Kenyon Review. She goes on, “The book explores classified redactions, erased testimony, and US-controlled secret prisons, or ‘black sites,’ renderings of which are included in the book. And like state-sponsored erasures, the silences in Sand Opera are multiple in source and purpose. An unpredictable structure of white spaces, grayscale, and black bars interrupt a multiplicity of speech. A series of vellum pages superimposed over lyrics, diagrams of Mohamed Farag Ahmad Bashmilah’s renderings of cells he was held in, a curious facsimile of Saddam Hussein’s fingerprints, and pages of complete black also disrupt the narrative, preventing closure or easy cohesion. There is not only one sort of palimpsest, not only one kind of haunting here. The visual experience makes the reading synesthetic—I kept thinking of the turning cylinder in a music box, the visual floods and silences as musical braille, my eyes the instrument.”

Joy Harjo, Weaving Sundown in a Scarlet Light: Fifty Poems for Fifty Years

Half a century of writing is a feat so remarkable that it fights language. May we all aim to be so dogged and capable (even a drop) as Harjo. The starred review of Weaving Sundown in a Scarlet Light in Library Review by Herman Sutter states, “Powerful, personal, and deeply spiritual, these are the poems of a prophet, and as with the words of the greatest prophets, they transcend both category and culture, speaking with an awe-inspiring authority as they draw on Harjo’s heritage as a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. ‘i want to go back / to New Mexico// it is the only way i know how to breathe’ says the opening poem, while the closing poem observes ‘We will find each other again in a timeless weave of breathing.’ Here are poems that have inspired readers and poets to see the world anew and listen to the unheard stories all around them.” And in its (to me) stressful “verdict” section? “Harjo is a national treasure, perhaps even a national resource, and this important book is an essential addition to contemporary poetry collections everywhere.”

Helen DeWitt, The English Understand Wool

The jacket copy of DeWitt’s novella states, “Raised in Marrakech by a French mother and English father, a 17-year-old girl has learned above all to avoid mauvais ton (‘bad taste’ loses something in the translation)…[T]his and much more she has learned, governed by a parent of ferociously lofty standards. But at 17, during the annual Ramadan travels, she finds all assumptions overturned. Will she be able to fend for herself? Will the dictates of good taste suffice when she must deal, singlehanded, with the sharks of New York?” John Domini in The Brooklyn Rail writes, “The English Understand Wool offers another spin snowball of a narrative, gathering weight as it slaloms the hills of Dewitt’s imagination. That trick gave us most of the brainy, bonkers collection Some Trick, in 2018, also delicious reading, by and large. Still, this new story delivers a deeper thrill, barbed yet sweet.”

Megan Fernandes, I Do Everything I’m Told

A book I feel I have seen everywhere and have yet to get my mitts on! A nudge to go out and get it. Rebecca Morgan Frank writes here in LitHub of I Do Everything I’m Told, “Megan Fernandes sets the tone for her third collection by opening with a love poem titled ‘Tired of Love Sonnets.’ Whether the speaker is having an ‘ugly cry’ before ‘hopping along’ at a K-pop dance class in Shanghai or asking a grocery store clerk whether they sell dignity, the conversational, playful movement of these poems bounces successfully off a formal control that extends to a ‘Fuckboy Villanelle’ in which ‘Eurydice’s tomb / was lousy with my amours.’ These aren’t simply poems about fisting films and exes–breast lump ‘debris,’ toxic masculinity, and ‘[losing] a job at a woman’s college to a dude’ bring different kinds of mourning center stage. As the speaker says, ‘One must look for signs / to believe in them.’”

Kristen Radtke, Seek You: A Journey Through American Loneliness

Named one of the best books of the year by over half a dozen venues such as Kirkus and the New York Public Library, Radtke’s graphic novel interrogates loneliness in a series of its manifestations. “Loneliness is a silent epidemic in America,” writes Gabino Iglesias at NPR. “It affects people in variety of ways and has adverse effects on our physical and mental health, but we collectively refuse to talk about it — and our understanding of its consequences is not as complete as it should be. Now, the lockdowns brought by the pandemic have made it worse. In Seek You, Radtke’s cuts to the marrow of our inner lives as well as our online lives and public selves to explore the ways in which community, interaction, and even touch affect us, especially when these elements are missing. Looking at everything from technology and social media to art and her own past, Radtke draws on a plethora of stories and personal experiences as well as scientific studies, writers, and philosophers to investigate how we interact with each other and what those interactions ultimately mean for our emotional, physical, and psychological wellbeing…The beauty of Seek You is that it feels like a communal experience. Reading this book is reading about ourselves and our lives.”

Bernadette Mayer, Midwinter Day

What new thing can I say about this incredible feminist, maternal, epic text? (Also, sidebar, how does this book not have its own Wikipedia page?) For the uninitiated, Mayer decided to write a long poem chronicling a single day—December 22, 1978—when her then-husband, Lewis Warsh, was being interviewed regarding his poetry. Their children were crawling all over Mayer when the interviewer turned to the remarkable poet and asked in a patronizing way, “So what do you do?” Or maybe it was “So you watch the children?” (Perhaps this is apocryphal—I can’t find it anywhere online—but a professor I trust told me this chronicle during my MFA.) Appropriately galled, Mayer decided to write something simultaneously ancient (an epic poem) and novel (about a single day in the life of a mother of small children). Mayer and Warsh had left New York for Western Massachusetts. The fact it was about family, the quotidian, in a relatively rural area made the work radical and enduring. Fanny Howe interviewed Mayer in 2019 about Midwinter Day in which Mayer stated, “So now it’s become for a lot of people, I think, a replacement for Christmas. So they don’t celebrate Christmas, you just have a gala reading of Midwinter Day, it’s so great. I love it, I never realized that it would be popular in that particular way.”

Hafizah Augustus Geter, The Black Period: On Personhood, Race, and Origin

A winner of the PEN Open Book Award and the Lambda Literary Award and with glowing words from Hanif Abdurraqib, Meghan O’Rourke, Alexander Chee, I’m wondering why The Black Period isn’t in my to-read pile. In its starred review, Kirkus writes, “In this elegiac text, a Nigerian American poet pays homage to her family while considering Black origin stories. ‘I’d been living inside the story begotten by white America,’ writes Geter, ‘but I’d been born into something else—what was it?’ She names this the Black Period, in which ‘we were the default.’ Born in Nigeria, the author grew up in Ohio and South Carolina. Having parents who ‘centered Blackness and art,’ she explains, ‘meant my sister and I were reared in a world that reflected our image—a world where Blackness was a world of possibility.’ Geter grapples with chronic pain and history (‘that thing that white people had gotten to write, but we had to live’) and culture in the U.S., ‘where I had so much in common with the enemy’s face America painted—African/Black, queer, a woman, child of a Muslim mother.’”

Bernadette Mayer, Milkweed Smithereens

Zucker conversed with Mayer in 2016 for her amazing podcast Commonplace and you can feel Zucker’s anxious energy while meeting a living legend who has had an enormous impact on her writing. At one point, she asks a question Mayer doesn’t like (“What is it like to be a crone?”). Zucker is feminist and reclaiming in her intention, but Mayer doesn’t feel it that way. As I listened, all I could think was a sympathetic “Oh no. Oh no oh no” as Zucker tries to clarify, save face, be honest with the last person perhaps on the planet she wanted to insult. The fact that Zucker kept the exchange in the episode illustrates her remarkable impulse to share moments most of us would hide from the world. Without artists like her—and Mayer who cut many of the paths Zucker follows—we would all be in trouble. Published just a few weeks prior to Mayer’s death, Milkweed Smithereens is the last poetry collection published during Mayer’s life. Mandana Chaffa at NBCC writes that Milkweed Smithereens “offers further proof of her importance in the contemporary American poetry landscape. Mayer’s poetry has always been an exuberant embrace of quotidian life—from the justly celebrated Midwinter Day to decidedly unstuffy sonnets, trenchant commentaries on politics, and gorgeous chronicles of nature—in ways lyric, funny, arch, multitudinous, and always true. There’s no loftiness in Mayer’s work and world.”

Elizabeth Strout, Lucy by the Sea

Lucy Barton, a recurring narrator of Strout’s work, makes a quick move from New York City to Maine because of the pandemic. Hamilton Cain reviews Lucy by the Sea for the New York Times, stating, “In Strout’s delicate, elliptical new novel, ‘Lucy by the Sea,’ Barton struggles with disbelief as SARS-CoV-2 vectors into the city, infecting — and in some cases killing — acquaintances. She’s mourning her second husband, David, a Philharmonic cellist who’d died a year earlier, when her first husband and close friend, William Gerhardt, a scientist, evacuates her to a rented house on the wind-cradled, sea-bitten New England coast…Strout writes in a conversational voice, evoking those early weeks and months of the pandemic with immediacy and candor. These halting rhythms resonate: Physically and emotionally Lucy is all over the map. Her feelings swing, pendulum-like, stirring up discord. When she upbraids William about a petty offense, he confesses that he had prostate cancer, sparking anguish and self-recrimination. Lucy begins to worry that she’s out of sync, a tension that Strout mines subtly. There’s no escape from the claustrophobia of Covid or family.”

Susan J. Elliott, Getting Past Your Breakup: How to Turn a Devastating Loss into the Best Thing That Ever Happened to You

Elliott’s book has landed on a handful of “What to Get Divorcées for Christmas” and “The Best Breakup Books.” It seems the book is built from her blog giving advice on the topic that makes up about 90% of all music, literature, and, it seems, general angst. Kathryn Schulz wrote in New York Magazine on the self-help genre, providing some history, “The expression ‘self-help’ comes from a book of that name, published in 1859 by the great-grandfather of the modern movement, one Samuel Smiles. (I kid you not.) These days, the phrase is so commonplace that we no longer hear the ideology implicit in it. But there is one: We are here to help ourselves, not to get help from others nor lend it to them. Unlike his contemporary Charles Dickens, Smiles was unmoved by appalling social conditions; on the contrary, he regarded them as a convenient whetstone on which to hone one’s character. As a corollary, he did not believe that altering the structure of society would improve anyone’s lot. ‘No laws, however stringent, can make the idle industrious, the thriftless provident, or the drunken sober,’ he wrote. ‘Such reforms can only be effected by means of individual action, economy, and self-denial; by better habits, rather than by greater rights.’ Smiles was Scottish, but it makes sense that his ideas received their most enthusiastic and enduring reception in the United States: a nation founded on faith in self-governance, belief in the physics-defying power of bootstraps, and the cheery but historically anomalous conviction that we all have the right to try to be happy.”

Rodrigo Toscano, Explosion Rocks Springfield

An excerpt of Explosion Rocks Springfield was in PEN Poetry Series. Brian Blanchfield, the guest editor, “Rodrigo Toscano’s forthcoming Explosion Rocks Springfield consists of eighty iterations of a kind of book-length system, a machine—as I read it—that runs class and labor and collective anxiety and grief through a single disastrous urban American incident, an event frequent enough to be generic, a lesser item in any news cycle. ‘The Friday evening gas explosion in Springfield leveled a strip club next to a day care,’ the journalistic title of each poem, resets the operations of an inquiry that moves in and around the news of a violent blast. These are five of the books’ poems, continually combustible at the limits of our untenable pressure.”

Sharon Olds, Balladz

In an interview Olds explains how, just after earning her PhD in literature, she yearned to return to writing poetry. “I said to free will, or the pagan god of making things, or whoever, let me write my own stuff. I’ll give up everything I’ve learned, anything, if you’ll let me write my poems. They don’t have to be any good, but just mine. And that is when my weird line came about. What happened was enjambment. Writing over the end of the line and having a noun starting each line—it had some psychological meaning to me, like I was protecting things by hiding them. Poems started pouring out of me and Satan was in a lot of them. Also, toilets. An emphasis on the earth being shit, the body being shit, the human being being worthless shit unless they’re one of the elect.”

Nicole Callihan, This Strange Garment

Nadia Colburn in Harvard Review writes of the recently published collection by Callihan, “This Strange Garment is written from the perspective of someone navigating breast cancer through the pandemic, and there are poems about tests, treatments, a mastectomy. But it is not a book about cancer; it’s a book about being alive… For Callihan, a poem becomes the space to hold all the strange contradictions of life, including, perhaps most importantly, the contradictions of the body itself, which is also ‘temporary.’ The book is ultimately a tribute to the female body, a body with breasts, even those that have been cut off, with nipples, even those resewn, with a belly button, and menstrual blood—all of which are described with a mix of specificity, respect, beauty, and humor.”

Katie Farris, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive

“In the face of medical vulnerabilities and the march of sudden illness, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive (Katie Farris’ full-length debut) embraces grief and wit, counters beauty with cruelty, and pairs eroticism with nostalgia,” writes Elisa Rowe in The Massachusetts Review. “Farris is a poet, translator, fiction writer, and Pushcart prize recipient. Her piece ‘An Untitled Collection of Generalizations that Mobilize the Eye’ was published in volume 60 number 3 of the Massachusetts Review and is included in the collection under the title ‘I Wake to Find You Wandering the Museum of My Body.’ A self-titled memoir in poems, the collection travels through the milestones of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, moments of pause, episodes of wonder, the concept of a corrupt country, and a global pandemic. Farris’ breast cancer is a seemingly central theme in the collection, but what propels the book forward are her body’s yearnings and her mind’s questions.”

Abigail Thomas, Safekeeping: Some True Stories from a Life

A BOMB Editor’s Choice, Suzan Sherman writes for the magazine of Thomas’ third-person memoir: “This is the story of Thomas’s life: she married at 18, had three children, and divorced eight years later. Then she moved home and lived in her parents’ basement. She explains, ‘It was 1968, but she was a child of the fifties, she needed a man. And not just any man, a husband. A husband who would provide her with a center. She has none of her own.’ So what does she do? She marries again, has another child, divorces, and marries the man whom today she is still married to. Thomas is now a grandmother and a teacher; she bakes apple cakes and chickens; she feeds. I gobbled this book down, all in one sitting. And then I did it again, wishing there were more of it. Thomas’s life, riddled as it is with complexities, births and deaths, promiscuities and regrets, swells on the page with warmth and authenticity.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.