The Annotated Nightstand: What Quiara Alegría Hudes Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Jamaica Kincaid, Toni Morrison, Elena Ferrante, and More

Quiara Alegría Hudes has earned serious accolades as a writer of plays, musicals, and memoir (Pulitzer, Tony, and Carnegie Medal longlist, respectively). With The White Hot, Hudes begins her foray into the novel.

The White Hot is a story within a story—it’s epistolary, a long letter from a mother who left a daughter behind eight years prior. We know the daughter, Noelle, is living with her father and stepmother, she’s about to graduate high school. This potent letter arrives for the abandoned Noelle to open upon her entry into adulthood: her eighteenth birthday. In the pages to Noelle that follow, April, the protagonist, gives a shabby portrait of the circumstances she ultimately left behind. Four generations of women shared a home in Philadelphia. April is in her mid-twenties, her daughter ten. April, like Noelle, is whip-smart and laden with “potential.”

But rage is the Achilles heel April passed along to her child. April names her anger “the white hot” of the title—what blurs her vision and lights up her body. The white hot is what ultimately sends April out the door after one too many clashes with an administrator over her daughter’s behavior, then her daughter and enabling mother and grandmother.

What follows is April’s journey that dilates from her original plan of eight days to eight years. In her letter to Noelle, we learn of April’s academic promise dashed when she became pregnant in high school, her ex who dipped during that pregnancy, the hushed traumatic secrets of their family, and what migration passes down.

“In The White Hot, Quiara Alegría Hudes has written the brown Latina modern-day Siddhartha that Hermann Hesse never saw coming,” writes Javier Zamora in his blurb. “Here is a necessary takedown of the patriarchy—a book written for everyone, but especially for those of us whose moms fled because escaping was the only option.”

Hudes writes about her to-read pile: “They’re all rereads for an essay I’m writing on what inspired my forthcoming debut novel, The White Hot. Here is my coven of women authors and their pariah creation—sometimes literal monsters, sometimes the monster of the desirous self. These books are deliciously, counterintuitively ethical—each one an instruction manual on a woman’s process of self-possession—many of them eschewing patriarchal morality and asserting a more dichotomous and sensual set of virtues. (If Frankenstein doesn’t seem to fit the bill, I read it as an allegory about motherhood and daughterhood.)”

*

Camila Sosa Villada, Bad Girls

Graciela Mochkofsky writes at the New Yorker how Bad Girls is “told by Camila, who is born poor and a boy in a town in the hills of Córdoba Province, and whose parents violently reject her when, as a teen-ager, she starts dressing as a girl.” Once Camila attends college, she turns to sex work to survive financially and is soon with people in similar circumstances but more experience “who teach and protect her, and with whom she shares daily doses of cruelty, pain, and humiliation but also of solidarity and joy.”

Jamaica Kincaid, The Autobiography of My Mother

“Kincaid’s third novel (after Annie John) is presented as the mesmerizing, harrowing, richly metaphorical autobiography of 70-year-old Xuela Claudette Richardson,” writes Publishers Weekly in its 1996 review. “Earthy, intractably antisocial, acridly introspective, morbidly obsessed with history and identity, conquest and colonialism, language and silence, Xuela recounts her life on the island of Dominica in the West Indies.”

Toni Morrison, Sula

Namwali Serpell writes about Sula, Morrison’s second novel, over at The Paris Review. “Sula is a real character, as we say. Sula is incomparable, matchless, singular. There is nobody like Sula. And yet. I’ve seen Sula in my days, in my sisters, my aunts, my friends, a stranger crossing the road.” Serpell continues, “The novel is named for a character whom we don’t really meet for thirty-odd pages. Sula begins instead with a fictional place—Medallion, Ohio.”

Elena Ferrante, The Lost Daughter

Joseph V. Tirella begins his review over at Works Without Borders with a quotation: “The hardest things to talk about are the ones we ourselves can’t understand.” Tirella goes on, “With that simple and unnerving sentence on the second page of this astonishingly economic novel, author Elena Ferrante is giving readers fair warning: brace yourselves, painful, discomforting truths are about to be revealed in this book about daughters and mothers and the women struggling to be both.”

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

David Naimon provides some powerful context for this 200-year-old novel in his recent interview with Olga Ravn, connecting it to Hudes’ reading of it as one about mother/daughterhood. “If you only see the movies, you don’t realize that in the book the monster is a deeply complex psychological figure with a depth of emotion and an intellectual life. I also think of how Shelley is writing this book while breastfeeding a second child, a child that would ultimately die three years later. She’s writing the book not long after losing her first child in its first days of life, a baby she has never named. She’s only 18 years old.”

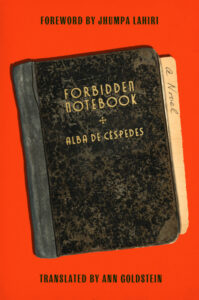

Alba de Céspedes, Forbidden Notebook

“Forbidden Notebook’s Valeria Cossati is a devoted mother of two adult children on the brink of independence,” writes Joy Castro at Los Angeles Review of Books. “She has always led a quiet, industrious life serving her family and dutifully fulfilling her various roles—until, one day in autumn, on a whim, she purchases a notebook and begins to chronicle her life…She does so stealthily, aware from the outset that to explore her own point of view can only trouble the smooth waters of domestic contentment.”

Magda Szabo, The Door

Emily Temple here at Lit Hub lists The Door on “The 10 Best Translated Novels of the Decade,” writing, “The plot is simple, even boring…Our narrator tells us a story from years before, when she, a writer whose career had been until recently held up for political reasons, hired a woman to help around the house. But she is no ordinary woman, and the novel is the story of their relationship, one which culminates in a truly extraordinary set piece.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.