The Annotated Nightstand: What Nicole Chung is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Lydia Davis, Thao Thai, Rebecca Makkai and more

Nicole Chung’s breakout bestselling memoir All You Can Ever Know, which earned her starred reviews in Publishers Weekly and Library Journal, described her experiences as a transracial adoptee from Korea, raised by white parents in a white community in Oregon. Chung dispels the usual clean narrative usually sold to the parents who adopt, the children who are adopted, considering her experiences of racism, birth family’s circumstances (which she uncovers). Her new memoir, A Living Remedy, focuses on her adoptive parents and other systems that impact her and their lives: healthcare, class, and capitalism.

As Chung enters adulthood, she gains perspective on what middle class living in the US often entails—a bit of money beyond monthly expenses, health insurance. Both of these realities were not the circumstances in her childhood home, where paychecks needed to be stretched to the limit. Chung’s surprise illustrates her parents’ hope to shield her from the fact of their poverty.

So, as an adult, Chung finds herself in a place depressingly quotidian but no less galling as a person who has more money and security than her parents, but is still far from comfortable. She is desperate to help them, but without the financial resources. Like so many Americans, she has student debt that is large enough it feels she can never pay it off. Soon both her parents are unemployed, uninsured, without a safety net. Her father cannot afford treatment for his diabetes or kidney disease.

Both kill him at the age of 67. Months later, during the height of the pandemic, her mother is diagnosed and dies of ovarian cancer. While the book is about undeniably about loss, Chung’s overall aim is to create a polemic against the healthcare system in this country, and illustrate how class difference exacerbates the terrifying vulnerability of the ill. She writes, “Sickness and grief throw wealthy and poor families alike into upheaval, but they do not transcend the gulfs between us, as some claim—if anything, they often magnify them.”

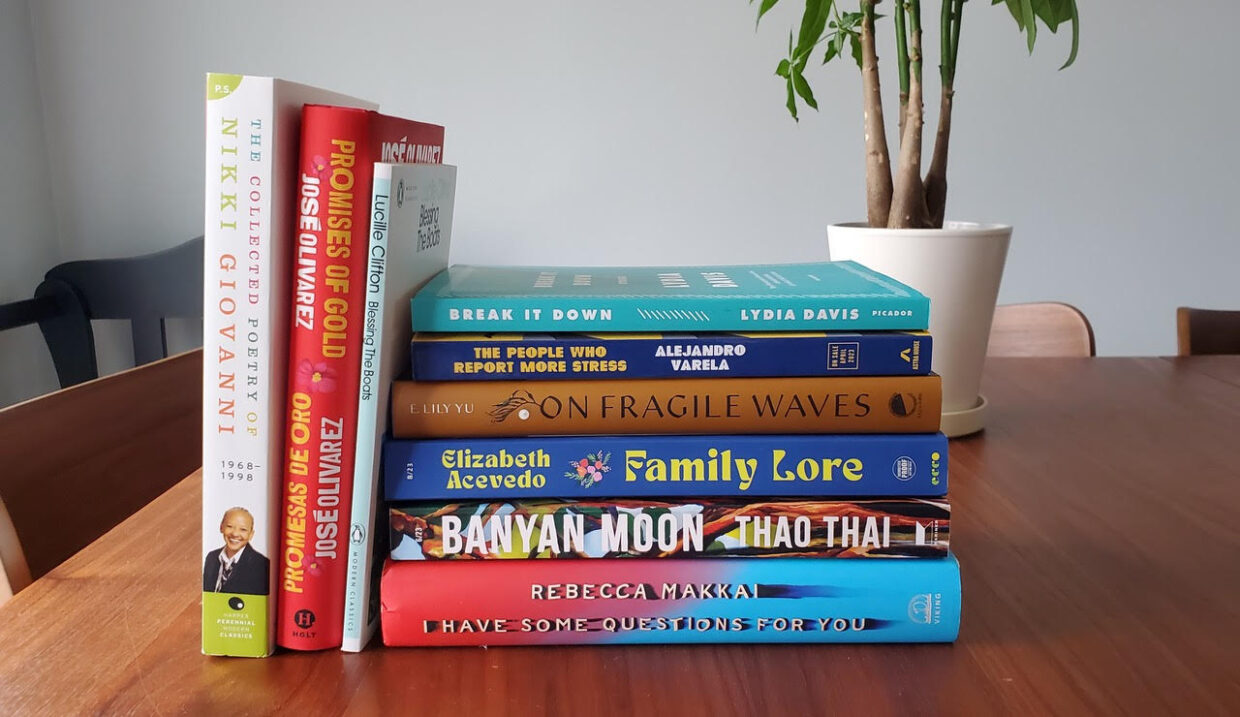

Chung tells us about her to-read pile, “These are the books keeping me company right now, a mix of books I’m reading and those I’m planning to tackle next—all for the pleasure or joy of it, not for work. (I purposely left out the titles I’m reading for work.)”

Nikki Giovanni, Collected Poetry 1968-1998

I love this insight into the inimitable Giovanni as a child in an interview: “I am a space freak. As a little girl, I shared a bedroom with my sister. And I got to sleep on the side of the bed facing the outside wall, so there was a window, and I would look out at the stars. I thought if I ran into a Martian and the Martian said, ‘Who are you?’ what would my answer be? The only answer could be ‘I am an Earthling.’ I realized — and have continued to realize — that it would be illogical if I were to tell the Martian I’m a Black woman. That’s because a Martian doesn’t know what Black is, and they don’t know what a woman is. So we know that race is illogical. It is a construct that is destructive… And if I could start Earth all over again, I would always make sure that if you had to answer the question, ‘Who are you?’ then you’d have to say, ‘I’m an Earthling.’ That way you don’t get trapped in what somebody thinks is your gender and your race. If Earth survives—there’s a good chance we’ll blow ourselves up—gender and race are going to go.”

José Olivarez, Promises of Gold/Promesas de Oro (translated into Spanish by David Ruano)

Olivarez was a guest just the other month! In its starred review, Publishers Weekly states, “‘[M]aybe we could redefine kin,’ Olivarez proposes, and these poems make a strong case for that redefinition, revealing how close bonds are an antidote to the world’s hardships. In one poem, the speaker details how their lover ‘kisses me on the cheek in a language/ that needs no translation.’ The poet’s sensitive and insightful voice allows these stirring poems to successfully explore the forces acting on love in a complex world, and the unshakable promise of understanding and belonging.”

Lydia Davis, Break It Down: Stories

What to say about an author who has changed the game regarding how short story writers think about economy, power, and character? Perhaps nothing novel, but I love the 1986 Michiko Kakutani review of Break It Down in the New York Times, with a photo of the young Davis. Kakutani appreciates Davis’ translation work and its impact on her fiction when Kakutani writes, “In addition to writing stories, Ms. Davis has worked as a French translator; and her stories not only demonstrate a cool, controlled use of language, but her heroes and heroines also share her awareness of words and inflection. Indeed they seem especially attuned to the ways in which language can betray you, its vagueness, inadequacy and susceptibility to misinterpretation.”

Alejandro Varela, The People Who Report More Stress: Stories

Varela was a recent finalist for the National Book Award for his first novel The Town of Babylon. He’s quickly back with a book of short stories. The titular short story was in Boston Review, and starts with our protagonist meditating on how he is terrible at catching cabs. The second paragraph reads: “The evening is tepid and sunlit, typical of August in New York City, but the cold in my bones is late winter. I’m on my way to buy a new phone, too weak from weeks of radiation treatment to walk the remaining twelve blocks. Three empty taxis zoom past, their on-duty lights taunting me. I wait for a familiar, neurochemical heat in my chest and face that doesn’t come. Even the audience of restaurant-goers dawdling across the street does nothing to me. Some of my composure is an unintended side effect of being an enervate survivor; some of it is calculated. Cancer reoccurrences are likelier in people who report more stress. I force a smile that I hope will dupe my body into thinking I’m happy, or at least keep the cortisol at bay. I don’t give up. I step further into the street and throw both arms in the air—a dare.”

Lily Yu, On Fragile Waves: A Novel

After great success in sci-fi and fantasy short fiction, Yu’s debut novel has received starred reviews in Library Journal, Publishers Weekly, and Booklist. Sheila Regan in Los Angeles Review of Books writes of On Fragile Waves, “The glimmers of joy experienced by the asylum seekers—who include young Firuzeh Daizangi, a 10-year-old when she arrives in Australia; her little brother Nour; and their Abay and Atay (mom and dad)—are often upstaged by the traumatic experiences of the family’s triumphant and tragic journey. Fleeing wartorn Kabul, Afghanistan, the Daizangis endure deadly ocean squalls, inhumane treatment in a detention center off the coast of Australia, and further degradation once they reach Melbourne, as the children attend school and the parents seek work. Amid horrific displays of mistreatment, disastrous run-ins with nature, and a sadness that threatens to swallow them whole, the book offers depictions of tenderness and the fierce love a family has for one another.”

Elizabeth Acevedo, Family Lore

Acevedo was the 2022 Poetry Foundation Young People’s Poet Laureate (a position for those who exert remarkable effort for children’s poetry in this country). Acevedo was an eighth-grade public schoolteacher for some years, and continues to work with incarcerated women and teens in Washington, D.C. In a brief profile of Acevedo, she states, “Being around teenagers all the time makes me aware of the emotional scale that they’re on and how they’re responding to things… If nothing else, it’s a reminder of how brilliant they are… Some adults write down to young people, but, if you listen to them, they’ll tell you what they need. Oftentimes, I think they’re more able to handle difficult subjects than we give them credit for.”

Thao Thai, Banyan Moon

Thai’s debut novel Banyan Moon is an follows three generations of women in a family. The Library Journal’s starred review says of Banyan Moon, “Successful Michigan-based artist Ann Tran has always felt a stronger connection to her grandmother Minh than to her mother, Huong. But when Minh dies and leaves Banyan House, the decaying home where Ann grew up, to Ann and her mother, Ann begins to question her beloved grandmother’s motives, lies, and nastiness to others. The novel’s three viewpoints and constantly changing time periods require some worthwhile concentration. Evocative descriptions of each locale add atmosphere and realism. Scenes of life during the Vietnam War add insight, and cameo appearances by the family’s deceased men are surprisingly moving and provide additional glimpses into the women’s lives.”

Rebecca Makkai, I Have Some Questions for You

Already a bestseller, Makkai’s 2023 novel is billed as a thriller, a whodunnit that circles around a dead high schooler the protagonist knew way back when. Katy Waldman in the New Yorker gives the book more dimension when she states it “joins a growing number of critiques of true crime, with Makkai charging the genre on three counts: exploiting real people for entertainment, chasing gore rather than studying systemic problems, and objectifying victims, most of whom are pretty, white, rich, and ‘young, as we prefer our sacrificial lambs.’ This last allegation evokes what Alice Bolin, in her essay collection ‘Dead Girls’ (2018), calls the Dead Girl Show, a modern-day myth in which an investigator develops a ‘haunted, semi-sexual obsession’ with ‘the highest sacrifice, the virgin martyr.’ Makkai ironizes a group of true-crime addicts, integrating criticism of the Dead Girl Show into her dead-girl show.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.