The Annotated Nightstand: What Natalie Eilbert is Reading Now and Next

Monica Youn, Mary Gaitskill, Patrick Radden Keefe, and More

In the spirit of full disclosure, a few years ago I edited Natalie Eilbert’s second collection, Indictus, for Noemi Press (which we actually discussed here at Lit Hub). Indictus largely attended to Eilbert’s experiences of sexual violence, as well as notions of innocence, justice, family, Jewish identity, trauma. One of the thrilling things about being an editor is seeing where authors venture once you’re no longer acting as a guide of some shape.

In Overland, Eilbert is looking at some of the same themes in Indictus—trauma, sexual violence, family—but, in addition, she brings in the vital thread of the environmental landscape and its multitudinous harms as an element within the emotional landscape. Or, as Library Journal’s starred review states, Overland is “A fine exploration of nature and self in crisis.” Eilbert writes of the

optimism of the lake outside my window.

That it is blue. That it is blue phosphorus

runoff, blue algal blooms, blue-tumored

muskrats slick in blue chemical afterlife.

Then, later, “I see the lightyear ago when I raced to Dad / standing at the door, always the surprise of arms, his jacket’s chemical smell.” What we love—associate with safety, hope—can and does poison us. We can’t trust much. There is a quiet intensity to this book despite the siren-blaring urgency of what she describes in these pages. Eilbert’s verbs, in particular, keep me on the edge of my seat. “We see the moths // fried to the bottom of bulbs as a lesson in pleasure,” she writes.

When Eilbert asks, “is there any house so strong it couldn’t burn?” this is about the Earth, but also, potentially, the self. While she interrogates the impact of a poisoned landscape on the body (cancer, illness, chronic pain, anxiety), the undertones between powerlessness in the face of environmental emergency is subtly set against powerlessness of sexual violence, yearning, loneliness, suicidal ideation and attempts. In short: the complications of having a body—whether yours, or the world around you.

And what does it mean to “have” these things? In her descriptions of suicidal ideation and attempts, I meditated on what it is to kill something precious. The self, the landscape—instantly or by terror-inducing degrees. Both create deep pain in those touched by the loss. With the land, it is, essentially, everyone—even if they don’t know it. This is thus a more complicated circumstance, harder to pin down.

Eilbert, like many Millennials and now Gen Z-ers, describes the difficulty of imagining bringing a child into this world (“The swirl of my daughter’s hair is silken, not there”) alongside her newborn nephew’s existence. “It isn’t clear when it will happen, but the next generation / sounds like a fantasy doesn’t it,” she writes, “why I stare and stare / at my nephew… the paradox of firm, healthy glow.”

I want to continually quote from this collection, as my descriptions feel drab in comparison to Eilbert’s charged language. Throughout Overland, Eilbert provides an intimate and fierce look at the dread so many of us know all too well, its many precipitators, both internal and external, and illustrates just how tightly the inside and outside are bound.

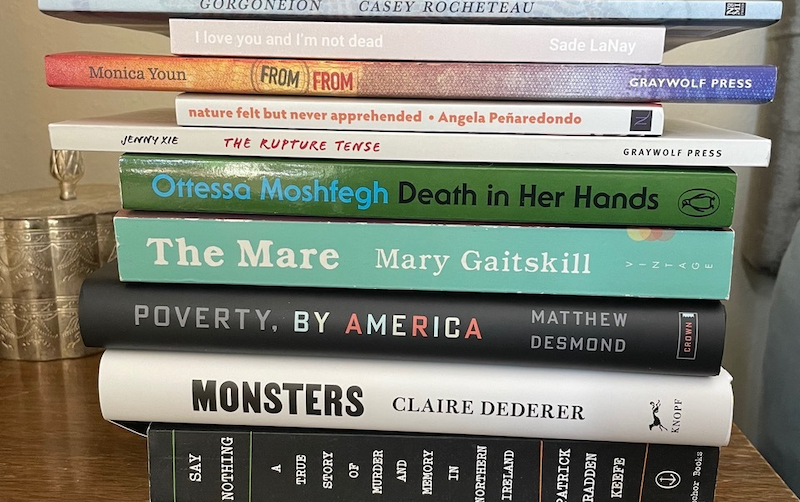

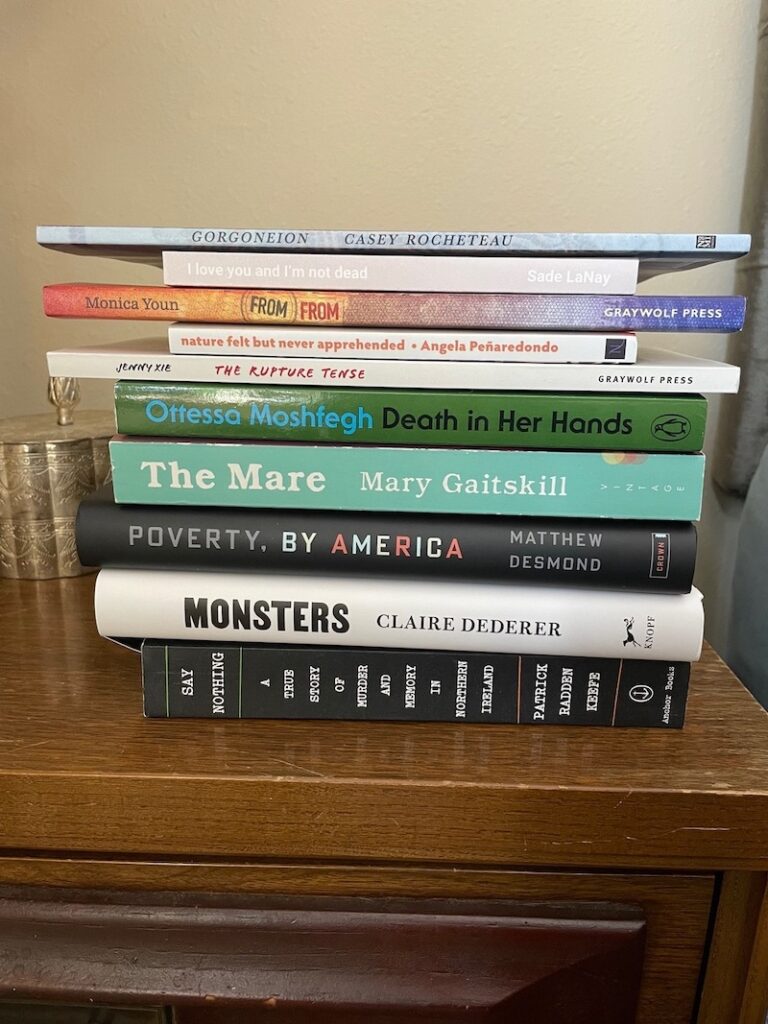

Eilbert says of her to-read pile, “I don’t know when it started, but I’ve always read three books from three genres at once. Call it the professionalism of the MFA that segments writing into fiction, nonfiction and poetry, or call it my utter dissatisfaction with singular focus. Why read in a way that runs counter to the mind? Above all things, I am interested in inquiry, that which wriggles and bends under our gaze. My books do not rest. The authors I adore mean to agitate and inoculate us to something new or novel or irrevocable. I want from a book what Clarice Lispector gives when she says, ‘To probe oneself is to recognize one is incomplete.’”

Casey Rocheteau, Gorgoneion

Another Noemi book, Rocheteau’s collection was a PEN American Open Book Award finalist this year. In an interview with Beth Maiden about their tarot deck, Rocheteau explains, “In most folklore, monsters are simply fears made manifest, and then in casual parlance we might do something that’s not in line with how we see our best selves and think ‘oh no, what kind of monster have I become?’ In order for that question to become anything useful it has to become something closer to ‘what fear do I have that caused this behavior, and how do I work with it so it doesn’t hurt other people or myself?’… I don’t want to vanquish the chaos or the darkness or my fear, all of that is actually necessary for universal and karmic balance and often comes from a hard-earned need to protect ourselves. To me, that’s probably a very queer idea, because the alternative is to suppress, ignore, sublimate and hide anything other than the okey-doke.” They explain, too, that Gorgoneion “started as an exploration of enemies and conflict as we were transitioning out of the Obama Era to the hellscape that has been Trump’s administration.”

Sade LaNay, I love you and I’m not dead

LaNay won the Lambda Literary Award for Transgender Poetry for this collection in 2021. The collection is largely prose poems, one of which includes the titular line: “Certain that you are not alone, even if you are lonely. As long as my words have the power to touch you, I love you and I’m not dead.” In her poem entitled “Entry 003 from I Love You and I’m Not Dead” LaNay writes, “New moon in midheaven, in Libra… Death rises to meet every face you meet. Ten wands whittled from prickly ash.” LaNay explains this poem “translates astrological data into images using correspondent and naturally-occurring magic and Tarot archetypes. The book where it’s included… is merrily mired in the denseness of language, reiterative layers of tone, register, and vernacular. Translation can be more elastic than a one-to-one exchange.”

Monica Youn, From From

It’s hard for me to do a post without referencing David Naimon and Between the Covers, and this is no exception. This is a book that’s also on my pile, and one of the elements that is exciting about it is Youn’s doubling between different figures/elements/themes. Two Youn and Naimon talk about for a while are Pasiphaë and Prince Sado. Pasiphaë (“from this family of witches out of Colchis… thought of as magical taboo and Asian”) was cursed by Poseidon to fall in love with a white bull, so she convinced Daedalus to craft a hollow cow so she could realize her desires. She gives birth to the Minotaur, which lives in a maze until it’s killed.

The 18th-century Korean Crown Prince Sado suffered from mental illness that manifested in brutal assaults of various shapes on those around him. In order to allow the succession of Sado’s son to remain intact, Sado couldn’t be tried for criminal behavior. Instead, his father ordered he go into a four-foot square rice chest, which was bound with rope and covered in grass until Sado dies. Her excellent poem “Study of Two Figures (Pasiphaë/Sado)” is long but accretes in the overlaps between these two figures. “The rice chest and the hollow cow are not the only containers in this poem. // Colchis and Korea are containers in this poem. // Asianness is a container in this poem. // Race is a container in this poem. // Each of these containers contains desire and its satisfaction. // Each of these containers contains discomfort and deterrence.”

Angela Peñaredondo, nature felt but never apprehended

This is the first time I annotate a book I edited—and it’s the most recent book I’ve worked on. I co-edited nature felt but never apprehended with Noemi’s co-publisher Suzi F. Garcia (we co- a lot at Noemi and it’s a wonderful thing). Years ago, I hosted Peñaredondo at a reading series in LA, and was captivated by the work she read. It was lyrical, complex, engaging with a wide variety of emotions including rage, quiet intimacy with family, diasporic ritual.

In her first poem, “[mercy ceremony],” we see a kind of spell cast over a figure that is the embodiment of the speaker’s subjugation. “what was stripped away from me is no longer an invisible assault buried under bladed tendrils of seaweed,” Peñaredondo writes. “there’s nothing holding me back from carving as one does when whittling wood… blow smoke into your one exposed ear so you can feel my life force / one last time.”

Jenny Xie, The Rupture Tense

In her poetry collection was National Book Award Finalist last year, Xie considers photographic negatives of Li Zhensheng—which number to almost 100,000—documenting the Cultural Revolution in China. Xie was born in China and immigrated to New Jersey at a very young age. This collection looks at the way the Cultural Revolution continues to impact. The wonderful poet and Srikanth Reddy in his New York Times review writes, “[Xie] prefaces ‘The Rupture Tense’ with a dedication to her grandmothers, ‘continuing, all tenses’; and she pointedly titles the book’s final section ‘Present Continuous.’ Here a poem, also called ‘Present Continuous,’ proposes that ‘the root of forgetting is the constant / rebuilding of the interior.’ It may very well be that the constant rebuilding we call identity depends on a kind of forgetting. The most resonant irony of ‘The Rupture Tense’ is that its author’s first language, Mandarin, makes no use of verb tenses at all. There are other, maybe countless, ways of giving shape to time.”

Ottessa Moshfegh, Death in Her Hands

Moshfegh is compelling and polarizing to many. What circumstances allow a writer get to be a model in a fashion show? And then there’s the i survived lapvona tote about her most recent book, Lapvona set in a medieval village ruled by a terrible lord. The tote creator writes, “Lapvona is a hard place to survive, but we did it! Let’s wear these as a badge of honor.”

In a profile in the New Yorker, she said something I do think about often: “The female genitalia—it’s so primordial, in a certain way. And I feel like, for us to get along and have codes of behavior, we can’t constantly be acknowledging that primordialness. We have adapted to a superficial environment, but I don’t know if the vagina has.” The inciting incident in Death in Her Hands is when a woman finds a note that states, “Her name was Magda. Nobody will ever know who killed her. It wasn’t me. Here is her dead body.”

Mary Gaitskill, The Mare

Gaitskill is the master of many things, predominantly the complex interiority of someone in crisis, or whose pains have accreted over time. The Mare is based in part on Gaitskill’s own experiences hosting children from NYC through the Fresh Air Fund. She describes this in an interview on NPR, and its conjunction with The Mare—a novel about a Dominican girl from Crown Heights who is upstate with an older Anglo couple. While there, she connects with a horse named Velvet (hence the title).

Gaitskill states, “I was just trying to think of how a child might feel in that situation… I can only imagine frightening for a 6-year-old to be put on a bus and go stay with a bunch of people that he doesn’t know. And whether they’re nice or not, it’s like why do I want to be here? Not to mention that they’re white as sheets and they’ve got more than anything you’ve ever had.”

Matthew Desmond, Poverty, by America

I wrote an annotation to this book in another “Annotated Nightstand” post. In 2016, Desmond won the Pulitzer Prize for his book Evicted, which followed eight families in Milwaukee through the wrenching experience of financial and subsequent housing precarity in the 2007-8 financial crisis.

In her review in the New Yorker, Margaret Talbot writes, “‘Evicted,’ which won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction, was almost universally acclaimed, praised especially for the vividness of its portraiture. So it’s brave, in a way, that Desmond has chosen such a different approach for his bracing new book. Books about the poor are vital, he says; they do the important work of ‘bearing witness.’ But ‘Poverty, by America,’ he explains, is a book about how and why the rest of us abide poverty and are complicit in it. Why do many of us seem to accept that the problem is one of scarcity—that there is simply not enough to go around in our very rich country? Where there is exploitation, there are exploiters, and this time Desmond sees many more of them, including most of his prospective readers.”

Claire Dederer, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma

An expansion of Dederer’s 2017 Paris Review Essay “What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men,” starts with a powerful list, the organizing principle of which becomes quickly apparent: “Roman Polanski, Woody Allen, Bill Cosby, William Burroughs, Richard Wagner, Sid Vicious.” Dederer attempts to parse, in the essay and the subsequent book, the complication that hounds us more and more regarding the artist/art split. When do we decide not to partake, and when do we think it’s fine? “They did or said something awful, and made something great. The awful thing disrupts the great work; we can’t watch or listen to or read the great work without remembering the awful thing,” she writes. “Flooded with knowledge of the maker’s monstrousness, we turn away, overcome by disgust. Or … we don’t. We continue watching, separating or trying to separate the artist from the art. Either way: disruption. They are monster geniuses, and I don’t know what to do about them.”

Patrick Radden Keefe, Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland

While I shrink from the phrase “a true story” in a subtitle—shrink further when “murder” is the word that follows next—it’s clear Keefe, author of Empire of Pain, is doing something more complex than a whodunit. Roddy Doyle’s review in the New York Times explains, “We follow people—victim, perpetrator, back to victim—leave them, forget about them, rejoin them decades later. It can be read as a detective story.” And yet, Doyle goes on, “It is about who owned the language, or got the most out of it… Violence joins injustice—it was the work of a marketing genius and the solid conviction of hundreds, thousands, of men and women: It was their war, their struggle.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.