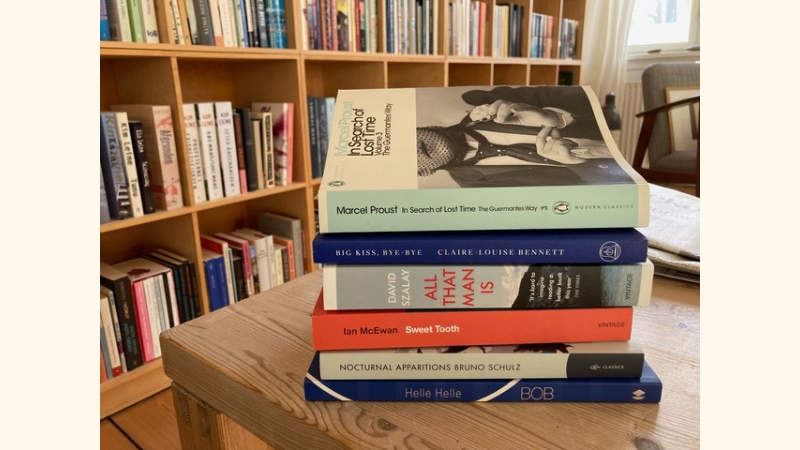

The Annotated Nightstand: What Martin Aitken is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Claire-Louise Bennet, David Szalay, Helle Helle, and More

I’m always happy to shine a light on a literary translator, and particularly thrilled to host this brilliant mind. Martin Aitken has already won my attention with his incredible translation of Olga Ravn’s otherworldly The Wax Child—hands-down one of my favorite books last year (and is a finalist for the NBCC Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize!). Now he has two more translation titles out in as many months: Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The School of Knight, and Helle Helle’s novel they (the focus of this column).

Set on the small island Danish of Lolland in the 1980s, they is a masterclass in how details and routine reveal the realities of a life. The “they” of the title are an unnamed teenaged daughter and mother pair. They are sweet with each other, deeply enmeshed, but easily so. Yet money is tight and they’re often forced to move house. There are rats in one place (“from now on they’ll sleep with shovels”), the sink that pulls off the wall in another, then another so damp it smells like wet wool. Despite, the daughter experiences some of the usual trappings of being sixteen—parties and boys, trying a high ponytail. She nods quietly when friends talk of Christmas trips and brie.

What sets the clock ticking is when the 41-year-old mother pronounces she feels pain in her chest in the novella’s early pages. Then someone mentions her trousers have become baggy. The daughter, clever, secretly calls the hospital and learns test results by pretending she’s someone else while her mother fixes dinner. “Six months, perhaps a year.” Then, immediately, the information from the phone bleeding into their home: “The dinner’s ready, they can eat now. They eat now.”

Despite the heart-wrenching plot, laughter is on almost every page of the book—but in plain description only. You’re on tenterhooks as you read, desperate to learn what the characters might reveal of their interiorities. Helle’s short declarative sentences are also defined by elisions, verbs, and juxtapositions. On frying a fish for dinner: “It’s eelpout, they muddy the pan. Her mother claps her hands together.” I don’t envy Aitkin, who must have had his work cut out for him—yet he manages it handily. His translations carry a music while also maintaining the sense that something is askew in a way that feels somehow fresh and enticing.

Aitken tells us about his to-read pile, as well as a tantalizing detail about a future translation: “All European. Re-reading Helle’s BOB before translating later in the year. Proust ongoing. And what a treat to realize there are still a couple of Ian McEwan’s books that I haven’t read.”

*

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time Volume 3: The Guermantes Way (tr. Mark Treharne)

The editor of this 2003 series, Christopher Prendergast, curated the seven translators of the epic works’ seven volumes—the first entirely new English translation of the work since the 1920s. Almost a quarter of a century later (be still my beating heart), people continue to bicker over whether this was a service to the text or a detriment. (Translated literature under more eyes is always a win, I think.) The aim was to make Proust more accessible, shaking off the purple prose in the earlier works. “For too long Proust has been ‘Proust’,” explains Prendergast, “held in an image bordering on idolatry.”

Claire-Louise Bennett, Big Kiss, Bye-Bye

Audrey Wollen reviews of Big Kiss, Bye-Bye at The Yale Review, saying the book is “about writing into and out of aging relationships, how sex hovers outside time,” and how this “felt like putting on a jacket you haven’t worn in a while, an old waxed jacket, and feeling around in its deep pockets, discovering a little pebble-like part of yourself: Oh, there’s that bit of yearning I’d lost track of. There’s that bit of yearning that’s tracked me like a dog after a fox.” And about the writing, “Bennett’s palindromish sentences thrum into the eternity of a single instance, holding the note, casting off false linearities.”

David Szalay, All That Man Is

“If David Szalay’s fourth book contains all that man is, as its title boldly declares, then pity the women,” writes Sam Jordinson at the Times Literary Supplement. “The males in these nine stories are variously introspective, drunk, violent, frazzled, over-heated, apathetic, even more drunk, suicidal and weepy.” Jordinson goes on: “Uncharitable readers may be tempted to dismiss Szalay as a misogynist. But this would be a mistake because his characters are so believable and his writing is so insightful.”

Ian McEwan, Sweet Tooth

Kirkus writes of this 2012 novel, “Both the title and the tone make this initially seem to be an uncharacteristically light and playful novel from McEwan…Its narrator is a woman recounting her early 20s, some four decades after the fact, when she was recruited by Britain’s MI5 intelligence service to surreptitiously fund a young novelist who has shown some promise. After the two fall in love, inevitably, she must negotiate her divided loyalties, between the agency she serves and the author who has no idea that his work is being funded as an anti-Communist tool in the ‘soft Cold War.’”

Bruno Schulz, Nocturnal Apparitions: Essential Stories (tr. Stanley Bill)

In 2019, the researcher Lesya Khomych discovered an unknown Schulz short story originally published in an oil industry newspaper. The translator of Nocturnal Apparitions, Stanley Bill, writes at Notes from Poland, saying the piece “is more frankly sexual than the later stories, which are mostly told from the perspective of a child. Here the adult narrator creates an atmosphere closer to Schulz’s erotic drawings, obsessively filled with images of the artist himself groveling at the feet of lithe young women. The new story almost forms a missing link between the graphical and literary phases of his creative life.” You can read more, and Bill’s translation of the story, here.

Helle Helle, BOB

A follow-up to they, BOB centers on the daughter of the pair, now shacked up with Bob, attending university. (Of all the young men circling her in they, I can only think, him?) The jacket copy explains, “She’s the novel’s narrator. But all she talks about is Bob’s life—especially the bits that don’t involve her.” “Helle Helle’s new novel is quite simply brilliant,” writes Marie Louise Wedel Bruun at Berlingske. “With her latest novel, BOB, Helle Helle shows that no one is as masterful at writing only what is necessary. With uncomplicated ingenuity, she shows us the difference between wanting to be free and being free.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.