The Annotated Nightstand: What Marci Vogel is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Joy Harjo, Myriam Gurba, Hua Hsu, and More

It’s that time of the year again when authors with titles that came out within the last twelve months hold their breath, bite their nails, look away, then pore over the end-of-the-year “best of” lists. (Perhaps it’s obvious—I’m among this group of poor souls this December. Be gentle with us!) At “The Annotated Nightstand” each turning of the Julian calendar year, I shine a light on a book that I feel deserved more attention. So many books got my heart going, were aesthetically fresh, rigorously made. A few: Roque Raqel Salas Rivera’s Algarabía, Shangyang Fang’s Study of Sorrow: Translations, Chris Santiago’s Small Wars Manual, Joni Murphy’s Barbara, Max Delsohn’s Crawl.

For this first of two posts on such books: Marci Vogel’s Xeno Glossia: An Illuminated Study of Christine de Pizan. Xeno Glossia is a profound and beautiful study of a woman who served as a court writer for the Medieval French King Charles VI. Christine de Pizan was first Cristina da Pizzano, an Italian girl born to a physician and astrologer. In one of the first big changes of fate for Cristina, her father became the astrologer to King Charles V, moving the family to Paris when Cristina was a girl. So Cristina became Christine, da Pizzano changed to de Pizan. The French royal court defined Christine’s life—she married a royal secretary, her daughter became a companion to one of the princesses. Yet Christine’s fate took a devastating turn when her father died, her husband was felled by the plague a year later. “Marking this devastating turn in a future codex,” writes Vogel, “Christine will inscribe a reproach: «Ah, Fortune, what a treasure you took from me!…You harmed the very character of my soul!»” Tangled legal issues denied Christine her husband’s backpay, and she soon realized she needed to find a way to support herself, her three children, mother, and niece.

Christine, whose father denied her his valuable knowledge when he lived (something she wrote about with disdain for this denial because of her gender—a remarkable expression, considering the time period), taught herself through the books in the king’s library. She began to write poetry, earning patrons and commissions from members of the royal court. Christine wrote through her dreams, referenced astrology and myth, and wasn’t afraid to comment on what she thought were the failings of political figures through allegory. Vogel quotes a bon mot of Christine, when a man “criticized my desire for knowledge by saying that it was not fitting for a woman to possess learning because there was so little of it; I replied that it was even less fitting for a man to possess ignorance because there was so much of it.”

All of this is plenty enough to keep you reading, as Christine is a compelling figure. That she survived financially by these means in such a time of political upheaval, and with writing alone, is remarkable. Yet Xeno Glossia throws us into the thrill of the archive, translation, and the Medieval world. Vogel gives us chronologies, scenes from Christine’s life in her own beautiful poems, prose about Vogel’s journey into the Medieval French royal court through treasured language dictionaries and rare books. Illuminated paintings grace many pages. Xeno Glossia operates in a range of registers to ultimately dimension to a woman and her life, connecting us over centuries. In these pages, Vogel thoughtfully probes, translates, and creates words left in Christine de Pizan’s shimmering wake.

Vogel shares a lot of wonderful thoughts about her to-read pile. She writes:

“California is my home state and I’m rarely outside of it, but for the last couple of months, I’ve been living in Cassis, France, as a fellow of the Camargo Foundation. I could’ve easily filled a suitcase with books just for the residency project, which includes translation of a long prose poem by Cairo-born francophone poet Andrée Chedid, but the weight limit is 50 pounds, so I took along a mini-iPad my mom gave me a few years back and use pretty much exclusively for reading, mostly because I’m all thumbs scrolling on its outsized onscreen keyboard. The Libby app allows free digital access to 30 books at any one time, and I’ve been stockpiling dozens of other titles in whatever notebook is handy. It’s crazy how many books I’m juggling just now, but beyond my current research and ongoing personal reading, I’m teaching three new courses next year—one on California authors, another on narrative forms, and another on environmental writing.

I did pack one physical book, Paul Ricœur’s On Translation (which, at 46 pages, barely registered on the luggage scale). One glitch in my travel reading strategy was the unexpected Book Soup inside the international terminal at LAX—with three hours before takeoff, who could resist? Luckily, Joy Harjo’s Catching the Light is small enough to be tucked into a pocket and large enough to contain multitudes. Whenever the news from home weighs heavy, I put down the iPad, turn off the cell phone, computer, and remote control, and hold fast to poetry.”

*

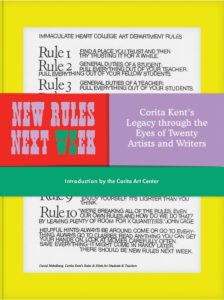

New Rules Next Week: Corita Kent’s Legacy through the Eyes of Twenty Artists and Writers

The jacket copy for this stunningly designed book states, “Known for her vibrant and powerful serigraphs, Corita Kent left an equally important legacy through her teaching. In the late 1960s, she and her students at the Immaculate Heart College developed their Art Department Rules… In this volume, ten writers and ten artists look back at the rules and show us how vital and resonant they remain today.”

John Freeman, California Rewritten: A Journey through the Golden State’s New Literature

“What else are we to do with a literature as capacious as California’s but keep the conversation going?” David Ulin asks at Alta on this book. “The writing of the Golden State is an expanding universe. To give it a shape and a structure, as well as to provoke new associations, to push the bounds of the conversation, Freeman has chosen to eschew chronology in favor of a set of thematically constructed sections. ‘The Suburbs,’ ‘Exploding Fantasias,’ ‘Who Is a Citizen?’: Each of these rubrics speaks to both what we think we know and what we need to know.”

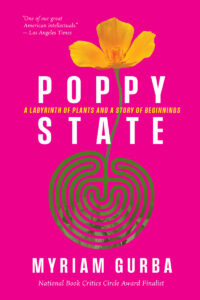

Myriam Gurba, Poppy State: A Labyrinth of Plants and a Story of Beginnings

Katie Lee Ellison writes at The Stranger, “Poppy State is Myriam Gurba’s labyrinthine creation through California’s plants, expansive markers and partners in her life, and the book itself, while it refuses the cliched delusion of catharsis so commonly found in American memoir, does offer a kind of return and a clearing. ‘California is many things to me,’ Gurba said, when we spoke. ‘Beyond this political entity with these arbitrary borders that we call a state that is governed by an asshole named Gavin Newsom. It’s a spiritual state, but it’s also the land.’”

Joy Harjo, Catching the Light

“The latest in the publisher’s Why I Write series,” Kirkus states, “Harjo, who previously chronicled her life in Crazy Brave and Poet Warrior, offers 50 vignettes that serve as signposts and steppingstones, showing how she began her artistic ‘venture…as an undergrad student at the University of New Mexico, a single mother with two children (and sometimes three), who went to school full-time, starting out as a pre-med major with a minor in dance, and changing the first year to studio art, my original career intent.’”

Lyn Hejinian, The Language of Inquiry

Susan Howe says of Hejinian’s touchstone book, “These essays, prefaces, lectures, aphorisms, portraits, and meditations, by one of America’s most innovative poets, passionately explore, as did the critical writings of Gertrude Stein, Marianne Moore, and Wallace Stevens, the philosophical foundations of contemporary American culture. [For Hejinian, the process of ‘theorizing is . . . a manner of vulnerable, inquisitive, worldly living . . . very closely bound to the poetic process.’]”

Brenda Hillman, In a Few Minutes Before Later

“This expansive text detects and forges vibrational fields in this unruly generation,” writes Susan McCabe at the Colorado Review, “addressing, as one poem articulates, our ‘unprecedented’ times with Northern California fires, the human impact on climate change, the grief and losses of the pandemic, complicit racism, the limits of activism…[and] captures the ‘thinginess’ of writing, refitted as a hymn to the unknown. Before writing there was song. The age speaks in fragments, as the book enacts.”

Hua Hsu, Stay True

The Pulitzer committee says of this winning memoir, “In the eyes of eighteen-year-old Hua Hsu, the problem with Ken—with his passion for Dave Matthews, Abercrombie & Fitch, and his fraternity—is that he is exactly like everyone else. Ken, whose Japanese American family has been in the United States for generations, is mainstream; for Hua, the son of Taiwanese immigrants, who makes ’zines and haunts Bay Area record shops, Ken represents all that he defines himself in opposition to.”

Harryette Mullen, Regaining Unconsciousness

“Regaining Unconsciousness recalls for me a previous book, Sleeping with the Dictionary,” says Mullen in an interview at The Brooklyn Rail, “which also explores embodied states of consciousness and unconsciousness in the mutual formation of self and other. Even (or especially) when contemplating abstract topics, poetry’s metaphors may default to the physical and conceptual body as common ground for understanding the world and how we inhabit it. I want my poems to be curious beyond my own life, inquisitive about the experience of others.”

Paul Ricœur, On Translation (tr. Eileen Brennan)

David Pellauer writes at Philosophical Reviews (which I love as a periodical title):“Translation as an issue was hinted at for a long time in Ricœur’s work on hermeneutics since it so obviously overlaps with questions about the nature of interpretation…He concedes that once translation begins, it will always include segments of untranslatability. By this, he means those inevitable failures or losses in transferring what is said in one language to another.”

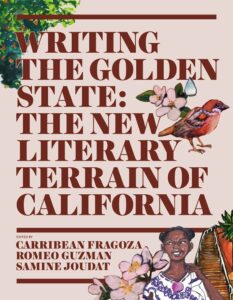

Writing the Golden State: The New Literary Terrain of California, eds Carribean Fragoza, Romeo Guzmán, Samine Joudat

At Latinx Pop Magazine, Cristina Herrera writes, “Rather than reinforce the hella problematic myth of California as the last vestige of a wide frontier begging to be ‘discovered,’ the essays in this volume explore those tucked away communities that would appear to be light years away from everything the iconic Hollywood sign represents. Who or what gets to be presented on a map? What and who does a map erase and bury? How can we (re)map a place and people into existence? These and more are just some of the questions the essays explore.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.