The Annotated Nightstand: What Maira Kalman is Reading Now and Next

A Series by Diana Arterian

Like many, I have adored the work of Maira Kalman for years. When I read “And the Pursuit of Happiness” in 2009 about her visit to Thomas Jefferson’s opulent home, Monticello, I immediately sent it to all my friends. I think about it at least a couple of times a year. In her simultaneously whimsical and artistic script, Kalman writes, “If you want to understand this country and its people and what it means to be optimistic and complex and tragic and wrong and courageous, you need to go to his home in Virginia.”

Recently out of college, this visual essay planted the potent seed that to understand the difficulties of our present, we must often look to the past. (Indeed, I took this even further to heart than most—on Inauguration Day, the day before the Women’s March in D.C., I listened to Kalman. My friends and I went to Monticello.) Her new book, Women Holding Things, is an expansion of a booklet Kalman made of just that, along with her own insights into what this means in its variety of forms (the historically famous and those unknown to us, physical objects and emotional states). The booklet came out in spring 2021, all proceeds going to organizations that help attend to food scarcity. It came along with a red balloon. The balloon had the words hold on written on it.

The prospect of reading and looking at Kalman’s work gets my heart moving like a squirmy animal. This is not a hyperbole. The excitement, I think, is in how she is able to locate the elusive sweet spot of poignant and funny, along with the often-dark complexities behind these emotions. I feel like I will learn something new about people, myself. Throughout her work, there is a desire to express everything and its wild excesses—how a person as violently, damnably flawed as Jefferson can also have held lofty beliefs and even executed some of them. Through her work, we see the humanity of people on the street, beloved pets, spousal grief, visits with performers and artists, extinct animals, family portraits. Her home of NYC is a recurring character. Colors and figures are lush and varied, and her desire to convey the tactile beyond her paintings (scanned journals pages, photographs, a dried leaf) gives it all more texture. In short: her work does something that feels, often, impossible. It conveys life. This piece, “The Optimism of Breakfast,” gives a good sense of what I mean.

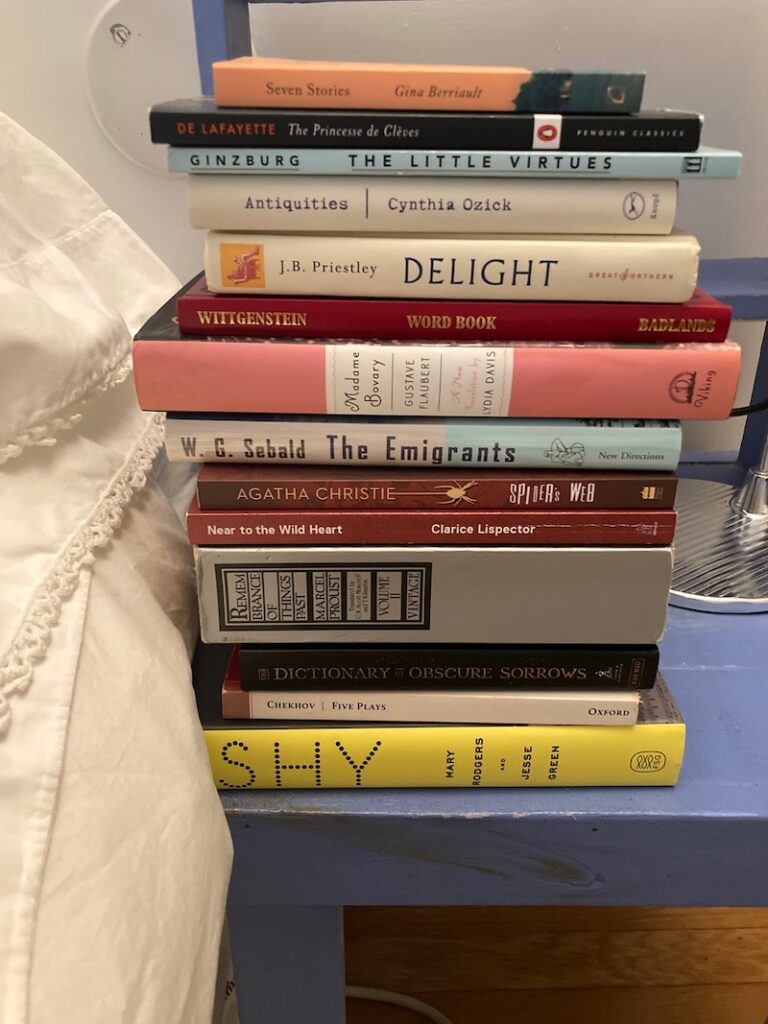

Optimism also makes an appearance in Kalman’s words about her to-read pile: “What can I say? That I believe I have all the time in the world. That I am optimistic that I will read everything there is to read. Something like that. I have stacks and stacks and stacks of books. I read before I go to sleep. I read in the morning. I read in the afternoon before a nap. I veer from the tragic and the lyrical to a nice crisp murder mystery. My favorites are always near. Proust. Chekhov. Sebald. Ginzburg. They keep me safe.”

Gina Berriault, Seven Stories

Berriault is a known master of the short story who subsequently earned many accolades during her lifetime. In “The Overcoat,” she tells of a son reuniting with his father after well over a decade. I can’t get over the description of the man seeing his father for the first time: “Granite, his father had turned to granite. The man sitting on the bunk was gray, face gray, skimpy hair gray, the red net of broken capillaries become black flecks, and he didn’t move. The years had chiseled him down to nowhere near the size he’d been.”

Madame de La Fayette, The Princesse de Clèves (trans. Robin Buss)

This novel is considered the first modern French novel, published in 1678 with no attribution. It’s set over a century earlier, in Henry II’s royal court. A sixteen-year-old girl marries a tepid suitor, only to meet her heartmate just after the wedding. She remains faithful to her husband, but intrigue ensues. Yet I find myself most drawn to author, a French noblewoman who pursued writing despite her anonymity. She was friends with François de La Rochefoucauld, met Racine and Boileau. She wrote and published three novels in her lifetime; three titles were published after her death in 1693.

Natalia Ginzburg, The Little Virtues (trans. Dick Davis)

This brief essay collection by the author covers a wide array of topics, best pinned down by Belle Bogs: “Some of the essays chronicle Ginzburg’s time in exile with her family during the Second World War; others compare the life she experienced in Italy with life in England, or the particular differences of preference and temperament between Ginzburg and her second husband…The title essay considers what we should teach children—’not the little virtues but the great ones,’ according to Ginzburg. ‘Not thrift but generosity and an indifference to money; not caution but courage and a contempt for danger; not shrewdness but frankness and a love of truth; not tact but love for one’s neighbor and self-denial; not a desire for success but a desire to be and to know.’”

Cynthia Ozick, Antiquities

In the prolific nonagenarian’s most recent book, Ozick places seven surviving classmates of a British-style boarding school-cum-retirement home together. They continue their callow attacks and postures that so often define youth, and is stereotypically endemic in elite prep schools. All seven are WASPs, yet our protagonist, Lloyd, returns time and again in his writing to his classmate Ben-Zion Elefantin. Lloyd was drawn to and infatuated with this red-haired boy who, Ben later tells Lloyd, is a Jew from the ancient Jewish community on Elaphantine Island in Egypt. Ozick attends to concerns of Jewishness, difference, and othering in this novel.

J.B. Priestley, Delight

I had not heard of this book prior to this to-read pile, but it’s so clear how Priestley and Kalman are speaking to one another through time. In 1949, a time largely marked by darkness after WWII, Priestly penned and illustrated this book of over one-hundred brief essays which describe that which delighted him. It captures a certain era and place, but also approach to life, as Priestley muses on the joys of “The Sound of a Football,” “Fountains,” “Trying New Blends of Tobacco.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Word Book (trans. Bettina Funcke)

In her review in BOMB, Corina Copp breaks down the philosopher’s book for us: “Inside this dictionary, meant for his elementary-school students, Wittgenstein places emphasis on the pedagogical need for regional usages, dialect, and colloquial expressions over the standard German they’d rarely encounter in the village of Otterthal, Austria, where Wittgenstein had moved to become a (by all accounts, quite intense) schoolteacher following his military service in World War I.” Yet this particular edition is special, as “a new, marbled edition from Badlands Unlimited features a translation by art historian Bettina Funcke, accompanied by Sharpie-delightful illustrations by Paul Chan, and an introduction from the Wittgenstein scholar Désirée Weber. A collaborative effort without question.”

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary (trans. Lydia Davis)

In the translator Lucina Schell’s review of Davis’ translation of Flaubert’s most famous novel, she writes, “Recognized by many critics as the first masterpiece of realist fiction, Davis’ translation feels absolutely contemporary, and takes nothing away from the radical innovation of Flaubert’s text…Flaubert was famously convinced that the style of this novel in particular, concerning such banal, psychological realities, would be critical to its success. This is clearly not as much the case as he believed, since generations of English readers have enjoyed the novel in translations that fail to adhere to Flaubert’s own stylistic strictures. However, we are fortunate now to have a translation that allows us to appreciate Flaubert’s style along with the entertaining story.”

W.G. Sebald, The Emigrants (trans. Michael Hulse)

At this point in the pile, I’m just thrilled by how much work near Kalman’s hand is in translation. It is something I know I aim for, and often fail to maintain. It’s vital we read work from all over the world, and from a variety of languages. Sebald is an author who, when I have read him, feel I am falling into a hole, the bottom of which I do not see. I am disoriented, but thrilled. His use of photographs, too, draw me in. To link it to another book in Kalman’s pile, Ozick reviewed this translation of The Emigrants, stating, “we are indebted to Michael Hulse, Sebald’s translator (himself a poet), for allowing us to see, through the stained glass of his consummate Englishing, what must surely be the most delicately powerful German prose since Thomas Mann.”

Agatha Christie, Spider’s Web

While largely known for her dozens of detective novels, this is a play by the prolific author. I did not realize Christie is the most successful best-selling author of all time, having sold more than 2 billion copies of her books. She is also the most translated writer in the world. Whatever snobs may think of detective fiction, these stories have undeniable reach! Spider’s Web is second only to The Mousetrap in terms of length of runs for Christie—and the latter holds a record for the longest initial run for a play (over 27,000 performances, essentially non-stop, since 1952). Christie described her likes and dislikes by her mid-fifties thusly: “My chief dislikes are crowds, loud noises, gramophones and cinemas. I dislike the taste of alcohol and do not like smoking. I do like sun, sea, flowers, traveling, strange foods, sports, concerts, theatres, pianos, and doing embroidery.”

Clarice Lispector, Near to the Wild Heart (trans. Alison Entrekin)

At 23, Lispector gave this first book its title from a quotation from James Joyce: “He was alone, unheeded, near to the wild heart of life.” Her translator, Entrekin, says of this Lispector, “Her turns of phrase are often peculiar, her word choices unconventional… There are places in her books where she is entirely idiomatic and makes perfect sense and places where every reader understands something different, because her sentences are open-ended, with words that contain a range of nuances, allowing for several different readings.”

Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past (trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin)

I remember reading that Anne Carson read a little bit of Remembrance of Things Past aka In Search of Lost Time every morning in the original French, and I pined to do something similar (I haven’t). It’s a lovely idea. It took her years to finish. In his 1981 review of Moncrieff and Kilmartin’s translation of Proust, Richard Howard (the amazing translator of Roland Barthes), writes, “Finished but incomplete, Proust’s work requires of us—readers and translators alike—an attention to details of linguistic creation we never granted to narrative prose, to ”the novel,” before (an attention we find similarly required of us in works of Joyce and Beckett, however): a sign of literary transformation to which the translator must dutifully, must drastically attend.”

John Koenig, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

The jacket copy for this compelling book reads: “Have you ever wondered about the lives of each person you pass on the street, realizing that everyone is the main character in their own story, each living a life as vivid and complex as your own? That feeling has a name: ‘sonder.’ Or maybe you’ve watched a thunderstorm roll in and felt a primal hunger for disaster, hoping it would shake up your life. That’s called ‘lachesism.’ Or you were looking through old photos and felt a pang of nostalgia for a time you’ve never actually experienced. That’s ‘anemoia.’ If you’ve never heard of these terms before, that’s because they didn’t exist until John Koenig set out to fill the gaps in our language of emotion.”

Anton Chekhov, Five Plays (trans. Ronald Hingley)

What more can be said about Chekov that hasn’t already been said? At the very least I’ll share what perhaps is not much known. A child of a tyrannically abusive father and storytelling mother, the family had terrible debts by the time Chekov was 16. In order to pay for his education, Chekov sketched for newspapers, tutored, and, my favorite detail, captured and sold goldfinches. At the beginning of his life as a physician, he often made extra money writing brief pieces that captured quotidian Russian life. Part of the reason he made so little is he never charged impoverished patients for treatment.

Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green, Shy: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers

The creator of the musical comedy Once Upon a Mattress, Rodgers in many ways lived under the shadow of her father, the musical theater composer who, with Oscar Hammerstein wrote South Pacific, The Sound of Music, The King and I (the list goes on and on). In the New York Times Book Review, this anecdote captures Rodgers’ voice and spirit: “As Mary used to say to friends as she reached for the check in a restaurant, ‘When your father writes “Oklahoma!” you can pay for dinner.’ Green notes it was a line she used frequently ‘because it acknowledged the awkwardness of the situation and swiftly walked straight through it.’”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.