The Annotated Nightstand: What Kendra Allen is Reading Now and Next

A New (at Lit Hub) Series by Diana Arterian

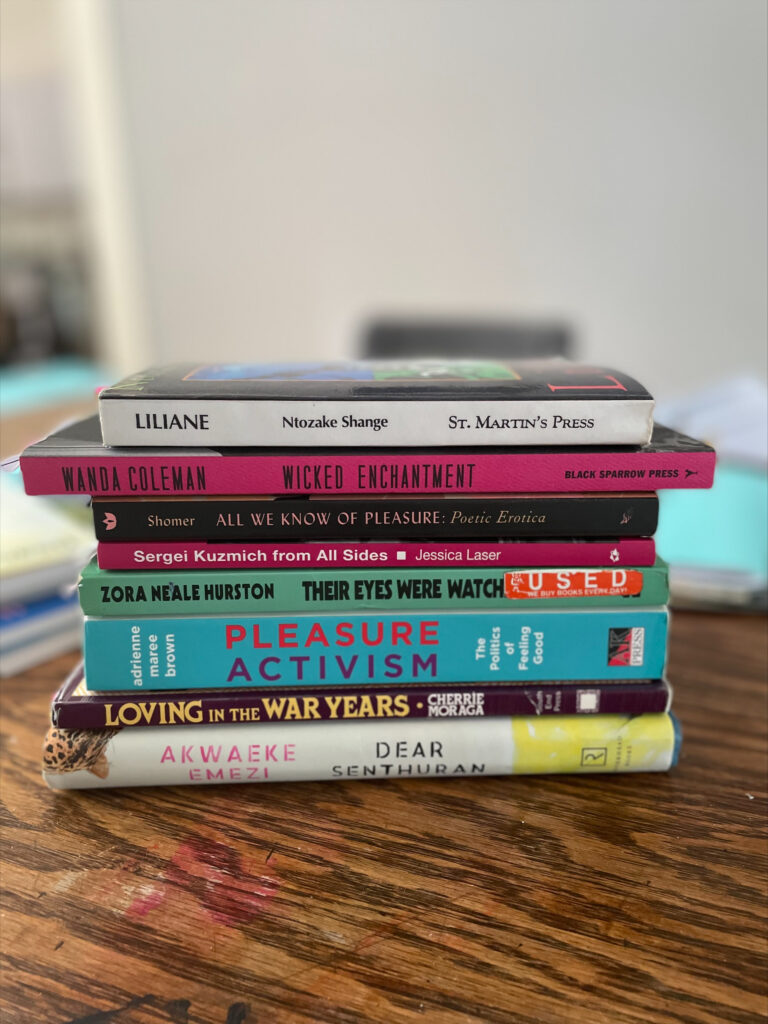

Kendra Allen is the kind of writer who can keep plates up and spinning. She’s a poet, essayist, and now, with her book Fruit Punch just out with Ecco, a memoirist. Her books have come out rapid fire over the last few years, with the recurrent themes of religion, family, trauma, Blackness, the South, growing up too fast. In her book of poetry, The Collection Plate, she writes: “I’m the queen bitch / up in here // and I love Our Father.”

While her essays and poetry circle around the different moments that have cultivated these concerns for her, Fruit Punch allows her the space to attend to them directly: growing up in Dallas, and in the family Southern Baptist church with the difficult requirements both of those entail for a Black girl in the 1990s. This along with the complication of her parents’ on again/off again relationship, and how that led to Allen’s codependence with her mother. While this seems like a bleak read (indeed, it begins with a friendly content warning from Allen herself), Allen is able to infuse the work with humor and periodic levity.

Beyond this, it’s clear on a line level she’s a poet—something I always love to see and feel in prose writers. Early in the book, she describes being a child under her favorite neighborhood pecan tree. “I use my baby teeth to pop the pecan shells perfectly,” Allen writes. “I learn how to do it so fast I obsess over keeping up with the rhythm. It go: Bite. Crack. Pull apart. Chew. Throw. Eat. Repeat.”

Allen says of her to-read pile: “I can turn to a random page in every single book here and be shown the necessity of accessing and entering want, and the freedom that follows desire when it’s done in consensual, critical, and creative ways; which is all I think I really care about writing and living at this point.”

Ntozake Shange, Liliane: Resurrection of a Daughter

It’s clear how Shange’s 1994 genre-bending novel connects with Allen’s interests. Prose poetry gives way to transcriptions of therapy sessions, which themselves give way to other voices giving monologues—through which we learn more about the titular character’s conflicts and desires. A visual artist, Liliane states at one point: “I’m not going to come out of my house until there are some hip black people in outer space.”

*

Wanda Coleman,Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems (ed. Terrance Hayes)

Coleman was generally considered the unofficial Poet Laureate of Los Angeles—her voice and work have left an indelible mark on the place, and the city is better for it. Hayes collected over a hundred poems of Coleman’s for this book, which is no small task considering she published over a dozen collections of poetry. “Words seem inadequate in expressing the anger and outrage I feel at the persistent racism that permeates every aspect of black American life,” Coleman wrote. “Since words are what I am best at, I concern myself with this as an urban actuality as best I can.”

*

Enid Shomer (ed.), All We Know of Pleasure: Poetic Erotica by Women

Shomer collected poetry from the last seventy-five years to illustrate the wide variety of eroticisms women poets can and do express. Lidia Yuknavitch says the book “is a breathtaking, eros driven, somatic poetic loveletter to women’s bodies. So many of the poets who changed my life and writing live inside this book, and isn’t that the truth of it, that poets give our desires and ecstasies back to us? I read it with my whole body, dripping with delight.” It includes work from Elizabeth Alexander, Adrienne Rich, Lucille Clifton, and many others.

*

Jessica Laser, Sergei Kuzmich from All Sides

In his review of Laser’s poetry collection, Cole Konopka writes, “Sergei Kuzmich from All Sides reflects multiple angles of a toxic relationship in which the partner is draining life from the speaker. Like most thoughtful works, Laser’s book complicates and diversifies rather than unifies its lyric thoughts, favoring the contradictory push-pull effect and affect in our lives. It’s a living book, or a book that lives in the real world through lyric. In its entirety, Laser’s collection is a reading experience that teaches about toxic love by example.”

*

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

I probably think about this book at least once a month since some brilliant professor assigned it to me in college. The ways in which Hurston interrogates the legacy of slavery in the United States, a woman’s sense of independence, access to love, agency, and pleasure. It was on TIME’s top-100 novels since 1923, and for good reason. If you don’t know the epic story of Alice Walker searching for and finding Hurston’s unmarked grave, give her 1975 essay “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston” a read.

*

adrienne maree brown, Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good

In her latest essay collection, brown attempts to answer the question, “How do we make social justice the most pleasurable human experience?” The jacket copy of the book reads, “Building on the success of her popular Emergent Strategy, adrienne launches a new series of the same name with this volume, bringing readers books that explore experimental, expansive, and innovative ways to meet the challenges that face our world today.”

*

Cherríe Moraga, Loving in the War Years

Originally published in 1983, Moraga wrote this collection of essays and poetry to provide a sense of her experience as a lesbian Chicana, and how growing up with these two identities provided particular complications in the political movements for what was generally regarded as isolated groups. This is a collection to address “lo que nunca pasó por sus labios,” she writes. I’m sad to see this book, even in its new expanded 2000 edition, is out of print. Some smart publisher will hopefully fix that for us all.

*

Akwaeke Emezi, Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir

Known for their best-selling 2020 novel The Death of Vivek Oji, Emezi is a writer for young adults and adults, who has earned a litany of awards and accolades for their work since it started to hit shelves in 2018. Emezi now turns their attention to their own life in Dear Senthuran. Kim Tran in the New York Times writes of the memoir, “It was not written for you or for me; Emezi is not concerned with such earthly things. This is a book about terms, and the agency we can afford ourselves by doing away with them altogether. It is also an audacious sojourn through the terror and beauty of refusing to explain yourself in the relentless pursuit of self-actualization.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.