The Annotated Nightstand: What Kate Briggs Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Mónica de la Torre, Roy Claire Potter, Ella Frears, and Others

“We all have mothers, but we don’t all break our lives for their sakes,” an early lover of the eponymous Lili of Lili Is Crying tells her, both of them in tears. While this man sums up the situation in a single sentence, others, including Lili herself, are not so discerning. Set in the pre-then-ensuing WWII Provence, we see many ways in which a young woman can be chewed up by life (heartbreak, small-minded friends, a botched abortion).

Yet the figure with the sharpest teeth is Lili’s mother, Charlotte, who is hellbent on keeping her daughter to herself. Lili should stay away from men, who are good for nothing anyway, she thinks. The instances in which Lili throws herself toward independence are doomed from the start. Nevertheless, she strains toward optimism and “enjoys daydreaming about happiness, for fear of never experiencing it in real life. Like a child.”

When Lili manages to flee and marry a man from Eastern Europe who loves her, they move down the road from Charlotte. When the man is hauled to Dachau, Charlotte considers this a stroke of luck—a moment that most reveals the ghastly darkness of Charlotte’s heart, but not the last. (She moves Lili back home along with the couple’s things.)

The setting of Lili Is Crying is on the heels of a period in which marriage was the primary way for a woman to flee the home of childhood—that leap from one place of domesticity (parents’) to another (husband’s). As the translator Kate Briggs writes in her afterword, “This is a novel all about interrogating what counts as ‘natural’ and ‘natural behavior’—between mother and daughter, between female and friends, between husband and wife, between hosts and guests, between nation states and their citizens.”

Bessette cannily illustrates the ways in which such moments of transition leave people lost—in this case between a woman’s life circumscribed by the home to a time of more liberty in the post-WWII boom. As social ideas evolve, wavering in the face of these changes, remaining fixed in uncertainty in how to behave, can be a trap.

Like her Modernist compatriots, Bessette focuses on the strangeness of time, in this case with interactions defined by the circular conversations and thinking. Lines repeat. What thoughts remain within the character’s head or makes it to their lips is purposefully unclear. This gives Lili Is Crying dreamlike, uncanny effect.

“The following scenes took place simultaneously,” Bessette writes at one point. “You have to be able to follow the one with your left eye, the other with your right.” This captures it. Her words light up with Briggs’ translation. When describing one of Lili’s (many) crying jags, she “is shaking, like a mouse caught in a trap.” Or a love affair defined by “Brief, brutal, burning couplings on hot dry rocks at the foot of the glaring ruins.”

What brought me (and many others) to Kate Briggs is her iconic book This Little Art. Through her descriptions of translating Roland Barthes’ lecture notes, Briggs gives a breathless intensity about falling in love with literature and its endless possibilities through translation. This Little Art has become a cult hit, and you can read an excerpt right here at Lit Hub.

(As an aside, This Little Art received a misogynist-driven hatchet job of a review—and then a blistering letter to the editor in response. If a bully comes at you and Emily Wilson, John Keene, Lydia Davis, Susan Bernofsky, Katrina Dodson, and other greats flock to your aid, it’s telling.)

Almost four years ago, Briggs published the first pages of Lili Is Crying online and, in what captures her aim to reveal more than conceal about the translation process, left all the English words about which she was uncertain underlined: “A flurry of wind,” Bessette-via-Briggs writes, “A block of stone crumbles.” (This ultimately became “A block of wall.”)

Briggs tells us about her to-read pile,

The thick book at the base of this pile (grubby from being carried about at the bottom of my bag), L’Attentat poétique, is a collection of papers given at the first conference dedicated to Hélène Bessette’s work at Cérisy-la-Salle in 2018, published in 2024 by Le Nouvel Attila, who are slowly republishing her complete works. It has been fascinating to translate a writer so committed to brevity, as well as to discontinuity, and even simultaneity.

Bessette’s thirteen “poetic novels” (in 1956 she co-founded “The Gang of the Poetic Novel” with her son) are all very short—novella-length. Recently, I have been seeking out or rereading books by contemporary writers who seem to be doing something powerful and similar: actively exploring what happens when poetry structures, enters or otherwise collaborates with the possibilities of prose (and vice versa). This is the reason for several of the books on the pile.

My hope is that Lili Is Crying will position Bessette as their newfound ancestor; a bold and persistent innovator to keep learning from. Other books have gathered here for different reasons. But looking at them as a collection I can see how they all connect in some way to what I am working on. Together they are both teaching me and making me think about the line and lineation, about place, about translation (always), about opacities, colors, color-action and the great light-source of the imagination.

*

Mónica de la Torre, Pause the Document

De la Torre was a recent guest in this column, where I wrote about this collection’s focus on the confusion of words (among other things). I wrote there,

Few periods of time seemed more apt for this description than the height of the pandemic, when time bent for so many of us it felt like it would snap (not to mention our minds or spirits). Throughout the poems that are in a variety of shapes and modes, De la Torre chronicles a series of moments from this period. Through our shared vulnerability of that time, the quotidian can be flush with meaning.

Roy Claire Potter, The Wastes

Phoebe Thomas writes in Stat,

Roy Claire Potter’s The Wastes maps topographies of grief and belonging on urban landscapes and rural land. Potter’s artistic practice, particularly their work with sound art, found text, and oral histories, shines through this narrative. It weaves offhand conversations, grocery receipts…into an honest tapestry that spans across the east and west regions of the North [England].

Nina Leger, Mémoires Sauvées de l’Eau [Memories Saved from the River]

This novel won the 2024 Prix du Roman Historique (Historical Novel Prize) and, though penned in French, its locale is California. In the novel, Leger attends to the very beginnings of the state’s gold rush in 1848 on the Feather River.

Its impact on the modern environment is made plain when the geologist protagonist must flee terrible wildfires there.

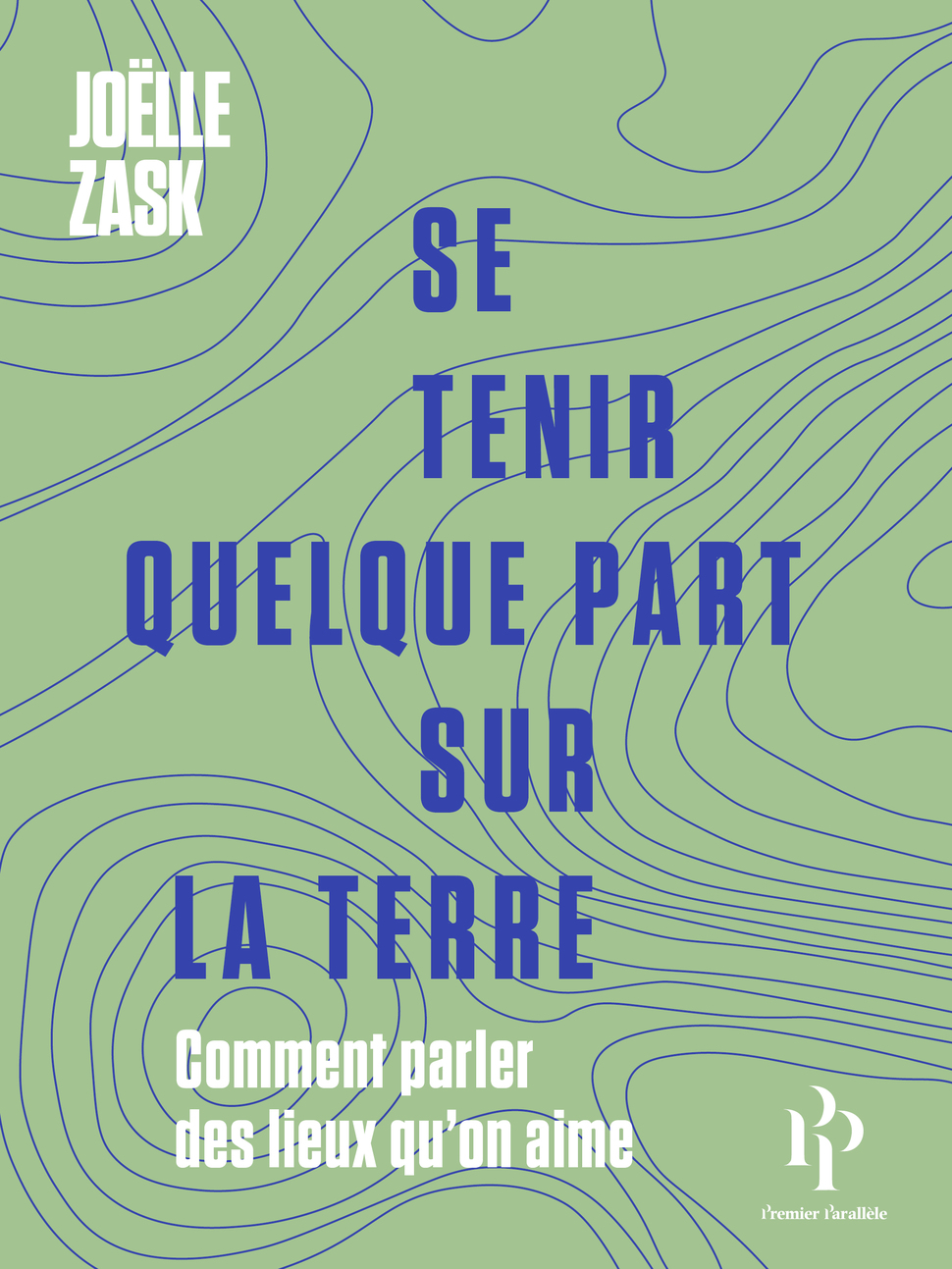

Zask is a contemporary French philosopher known for, among other things, translating the works of the American philosopher John Dewey. There is a reason Zask has done so much to bring Dewey’s writing into French: she, too, focuses on democracy in her work.

With this book, Zask attends to notions of personal geography, belonging, and politics.

Duncan Wiese, Tityrus: A Pastoral (trans. Max Minden Ribeiro and Sam Riviere)

In a blurb, Denise Newman says of this translation from the original Danish,

Duncan Wiese’s subversive pastoral Tityrus shows how fraught life has become for the Arcadian shepherds among us. Refusing to sugarcoat Tityrus’s experience of our fetid and worn-out world, Wiese uncovers the daily pathos and absurdities of contemporary life. This spare yet encompassing verse narrative, deftly translated by Max Minden Ribeiro and Sam Riviere, provides an insightful and haunting portrait of our time.

A.S. Byatt, Ignês Sodré, Imagining Characters: Six Conversations about Women Writers: Jane Austin, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, Willa Cather, Iris Murdoch, and Toni Morrison

“Bestselling novelist Byatt and psychoanalyst Sodre cultivate the art of literary conversation,” writes Kirkus. “The underlying premise is that literature in general, and the novel in particular, is a unique and important form of knowledge that calls upon its readers to carry on its imaginary world in conversation and discussion. Both Sodre and Byatt are shrewd readers, as well as voluble conversationalists.”

Ella Frears, Goodlord: An Email

“When I tell you that poet Ella Frears’s new ‘novelistic text’ takes the form of one long email to a landlord, you might balk,” writes Holly Williams at The Guardian. “You shouldn’t.” She goes on, “We’re whisked through the narrator’s life, from wincingly recognizable schooldays and bad jobs in bars to brilliantly eerie artist residency. Her hunger for a home…is repeatedly thwarted, the grinding inequalities entrenched by the housing market exposed with a frustration that’s laced with wit.”

Marion Milner, On Not Being Able to Paint

In none other than Anna Freud’s foreword to this book, she writes, “The amateur painter, first puts pencil or brush to paper, seems to be in much the same mood as the patient during his initial period on the analytic couch….Marion Milner’s book is written throughout from an eminently practical aspect of self-observation and expression.”

Yoko Tawada, Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel (trans. Susan Bernofsky)

Sylee Gore writes of Tawada’s book in Words Without Borders,

this book revolves largely around character and experience. We are treated to meditations on subjects ranging from populism, warfare, nationalism, and migration to memory, multilingualism, and the twentieth-century Jewish poet Paul Celan, all filtered through [the protagonist] Patrik’s eccentric consciousness and moving at furious velocity.

Julien Doussinault (editor), Claudine Hunault (editor), Cédric Juillon (editor), Hélène Bessette: L’Attentat poétique

As Briggs mentioned above, this is a volume of papers presented on Bessette as a conference in 2018. A wild thought considering, as Briggs puts it, Bessette “died in poverty, in poor mental health, in 2000, her body of work (thirteen novels in total) out of print, her singular articulation of what, with specific intent, she called ‘the poetic novel’ under-recognized and, until recently, forgotten.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.