The Annotated Nightstand: What Jennifer Hope Choi Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Ross Gay, Isabella Hammad, Chet’la Sebree, and Others

Choi, a senior editor at Bon Appétit has written about her family, inherited experiences, and those that trail her from childhood in her essay “No Vacation Is Complete Without a Cooler Full of Gimbap.” The cooler filled with gimbap—”laver seaweed (gim) wrapped around a rainbow of vegetables and rice (bap)”—was painstakingly prepared by Choi’s grandmother, providing the family with sustenance for days as they drove from California to the Midwest.

“I wanted the American food that matched an American vacation,” Choi writes. “If left to my own devices, I could’ve mainlined ranch dressing all the way to South Dakota and back. As a nine-year-old, I didn’t understand yet the sacredness of our homemade food.”

Choi’s new book, The Wanderer’s Curse, attends to similar concerns, though from a different valence. Through the memoir’s pages, Choi traces her growing understanding of herself through her twenties and thirties alongside understanding her mother—the origin of so much of Choi’s sense of self.

Though mother and daughter were once close when Choi was a child, they drifted apart by the time she was a teen. “I suppose she had grown to despise me the way I despised her,” Choi writes, “because we came from each other.”

“I never should have raised you American,” her mother tells her at one point. “If you were a real Korean daughter, you would just sit there and listen. Like a wall.”

Unsurprisingly, Choi flees her home in California for college and a wayward-adjacent life many in their twenties in New York savor. Then her mother, the cornerstone of Choi’s family, undergoes a wild transformation. In the wake of Choi’s father’s infidelities and the dissolution of their marriage, her mother “dyed her grey hair orange, teased and pinned it up with glitter-spangled butterfly clips.” Her staid outfits that befitted her personality are swapped for a bolero covered in sequins and flared jeans.

Though Choi’s mother moved the family with undeniable abandon throughout Choi’s childhood, she begins to send herself further and further afield, traveling through Europe and moving, on a whim, to Alaska. Then Choi herself becomes uprooted, pulled into the itinerant life her mother has put into practice for so long. At one point her mother texts, “We r so much alike it is scary.”

For a few months, mother and daughter live together in South Carolina after Choi can’t make ends meet in New York. This time helps mend much of what generational and cultural differences, not to mention the battlefield of adolescence, had rent.

Later, when visiting Korea with her mother, Choi undergoes two saju readings (a Korean divination practice). Both confirm that Choi has yeokmasal or “the wanderer’s curse.” At a more formal reading, with Choi’s mother acting as a translator, Choi learns she and her mother both definitively have yeokmasal. “We’re similar, aren’t we?” Choi’s mother asks. But—“I have more yeokmasal than you.”

Choi tells us about her to-read pile,

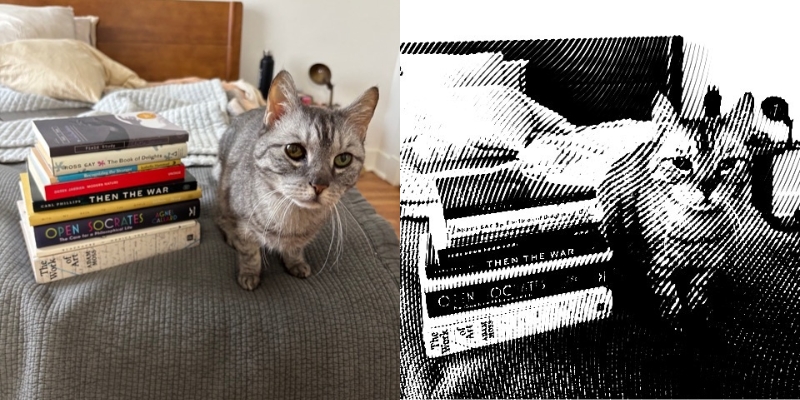

I’m a bed writer (where my bed writers at?!) which means I have embarrassing posture and a nightstand that acts as a desk area of sorts. My book, The Wanderer’s Curse, took roughly fourteen years to write, and many of the pieces in it ostensibly function as long essays.

Everyone wants short material these days, but I decided that the only place you can write a long-ass essay is in a book, so I leaned into that, which allowed me to connect seemingly disparate ideas and themes with a kind of distilled nature but with a lot of room to breathe life into the material. Now, I want the opposite—experimentation, brevity, bitsy-ness.

I’m beginning to circle around a potential new project, so my pile (which is often strewn beside me in bed) is focused on shorter story forms or topics that intrigue, challenge, and maybe even confuse me: diary, lecture, process, and always poetry.

*

Chet’la Sebree, Field Study

Jay Gao at The Poetry Foundation states in his review of Field Study,

Addressed to a white man Sebree once dated, Field Study uses this scrutinized timeline to form the wounded attachment as a means to explore Black sexuality and desire, interracial relationships and misogynoir, vulnerability and joy. As Sebree walks us through a history of psychoanalytical “harmful intimacies,” we encounter a fieldwork that is inflected—or invaded—by its unstinting array of references and quotations, ranging from Mean Girls to Audre Lorde.

Unravelling “between love and decimation,” Sebree’s open field carries us from psychic site to site, from a bed to a bar to a school, asking us what it means to unapologetically survey, to revisit.

Ross Gay, Book of Delights

This book which, to me, was a vital buoy during the height of the pandemic, gives dimension to joy, delight, and beauty. Gay, as always, doesn’t come at something superficially, but in a way that bolsters as it challenges. “One of the projects of the book is allowing oneself to be moved,” Gay says in an interview at NPR.

And I think one of the studies in the book is that to be moved is to be connected. To be moved is to be alive. I think for any number of reasons, I have wanted to participate in the brutal fantasy of not being movable. I’ve wanted to imagine myself as a discrete creature that is not movable. You know, I grew up playing college football, and a lot of my training was about how to be unmovable.

But to be moved, it’s all kinds of things. It’s tears, and it’s shock and it’s flabbergasting. And it feels like a profound sorrow when I am reluctant to say, I love this, I love this. I’ve never seen anything as beautiful in my life; that flower gives me a reason to be alive.

Isabella Hammad, Recognizing the Stranger

This vital book is in a lot of to read piles (as it should be—and you can look at Hammad’s own TBR pile for this column here). Again, I point to the excellent interview with David Naimon on Between the Covers, in which Hammad says,

We don’t know what that endpoint’s going to look like. We also know it won’t actually be the end in some ways. Liberation always is followed by many complications and state building and all of these things and everything else; we know from other anti-colonial movements and their afterlives….

I guess part of the reason I ended up writing the lecture about [turning points] is I was wondering why am I so interested in it, why am I so interested in people’s capacity or not for change. I always ask people what texts did they read, what experiences did they have that changed their attitudes to things.

What I’m really usually asking about is what changed their attitude to Palestine. I’m always interested in the development of political consciousness, how it forms, how we understand ourselves, not only as individuals but as part of groups, as part of something larger, as part of an epoch, and that makes its way into my writing. I unpacked that and realized it was because of Palestine quite specifically.

Derek Jarman, Modern Nature

It’s always exciting for me to learn about new artists and writers for this column (as hard as it is to own my ignorance about such towering figures as Jarman). For the uninitiated like myself, Jarman was an artist and filmmaker whose work is as varied as the meditative 1986 film Caravaggio about the Baroque painter and Sebastiane about the saint’s death to a short film for The Smiths and another for The Sex Pistols. His work and interests were a composite of the modern and historic, working with Judi Dench, Tilda Swinton, and The Pet Shop Boys.

Just as importantly, Jarman was openly gay at a time when there was more explicit hostility to queerness than today, and a powerful advocate for gay rights. He also was public about his AIDS diagnosis and the impact on his health up to the end of his life, at the age of fifty-two. The Village Voice writes of Modern Nature,

Epiphanies infuse Modern Nature, Derek Jarman’s diaries from 1989 to 1990, with their ebullient evocations of gardening. For Jarman, planting flowers at his wind- and sea-blasted cottage and then reciting their names (endlessly, passionately) becomes sex, becomes the fullness he’s on his way to leaving as he grows sicker from AIDS.

You can watch a video about Jarman’s super-8 films over at the Tate.

Victoria Chang, With My Back to the World: Poems

If you attend AWP, you inevitably miss things you wish you had made. I was hoofing it to “Eyes Wide: Exploring the Extended Ekphrastic,” and just missed Chang’s talk that attended to With My Back to the World. This was her description, and I still curse myself for not getting there on time!

In my talk, I’ll be discussing how the ekphrastic and the artwork and writings of Agnes Martin and On Kawara allowed me to get at difficult emotions that I was feeling related to sadness, the inadequacies of language, being seen and seeing—and on this last one, I had to look at something in order to explore perception. Some of my poems explore the nature of seeing and being seen in a digital world.

My artistic practice in these poems seems committed to rethinking our relationship to what is diminished—which is the personal, which is privacy, and bearing witness to that diminishment. Maybe some of us need both art and writing when we sense that neither is enough. Or that the interaction of the two can create something else, something larger.

Agnes Callard, Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life

Jennifer Szalai writes of Open Socrates in the New York Times,

This is a book that is charming, intelligent and occasionally annoying. The irritation is wholly appropriate: Socrates, whom Callard affectionately calls a “wet blanket,” was known for challenging his interlocutors to the point of exasperation, pushing them to think harder about whether what they had just said was what they truly meant.

“I realized, to my sorrow and alarm, that I was getting unpopular,” Socrates ruefully reflected, after having alienated a number of powerful politicians in Athens and before being sentenced to death. Callard was so enthralled by Socratic philosophy as a college student that she wanted to “be Socrates” and set out to hound strangers at an art museum with big questions about the meaning of life.

“They felt trapped,” she recalls now, “and I felt not at all like Socrates.”

Monica Youn, Blackacre: Poems

In an interview with Kaveh Akbar at Divedapper, Youn says of this collection,

a big question in the book is “How deeply rooted are these stories and archetypes?” If I think about what the method of the book is, or what the argument of the book is, it’s something like “We have to live somewhere.” We’re always already situated. Each of us inhabits a body and we can examine that body and we can dismantle some of the assumptions we’ve used throughout our lives with regard to that body.

We can tell ourselves that those stories we were told were wrong, invidious. Those desires and ambitions that we had were externally constructed and based on terrible values. Those understandings were false and damaging. But at the end of that, you are still in that same body. So, what is left of the self once you take apart the organizing assumptions of the self?

We live in a society, in a social structure, in a nation and we can criticize the historical foundations and the founding assumptions of that and we can start taking that apart and diagnosing its pathologies. That’s work we can and should do, but at the end of that, what are we left with? If the disease goes bone-deep, how can you continue to survive in a body without its skeleton? We still have to live in that same body, that same acre. It’s all we’ve been allotted.

Adam Moss, The Work of Art: How Something Comes from Nothing

The “Briefly Noted” in the New Yorker says,

This collection of interviews, by a former editor of New York, aims to illuminate artists’ processes through conversation. The novelist Michael Cunningham describes writing first thing in the morning to avoid getting ‘lost in the realness of the real world’; the visual artist Kara Walker recounts beginning one project by drawing with her feet (“I can’t trust this hand not to make something very obvious”). Moss’s footnotes flag common themes, including tenacious work ethics, mentorship, and iterative revisions. His subjects’ accounts are enriched by color images of works in progress: the outline of a concerto (Nico Muhly), a line of poetry scribbled in a faculty meeting (Louise Glück).

The Work of Art includes interviews with Kara Walker, Tony Kushner, Roz Chast, Michael Cunningham, Marie Howe, Gay Talese, Cheryl Pope, Samin Nosrat, Ira Glass, Simphiwe Ndzube, Will Shortz, Sheila Heti, Gerald Lovell, Jody Williams & Rita Sodi, David Simon, George Saunders, Suzan-Lori Parks (among many others).

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.