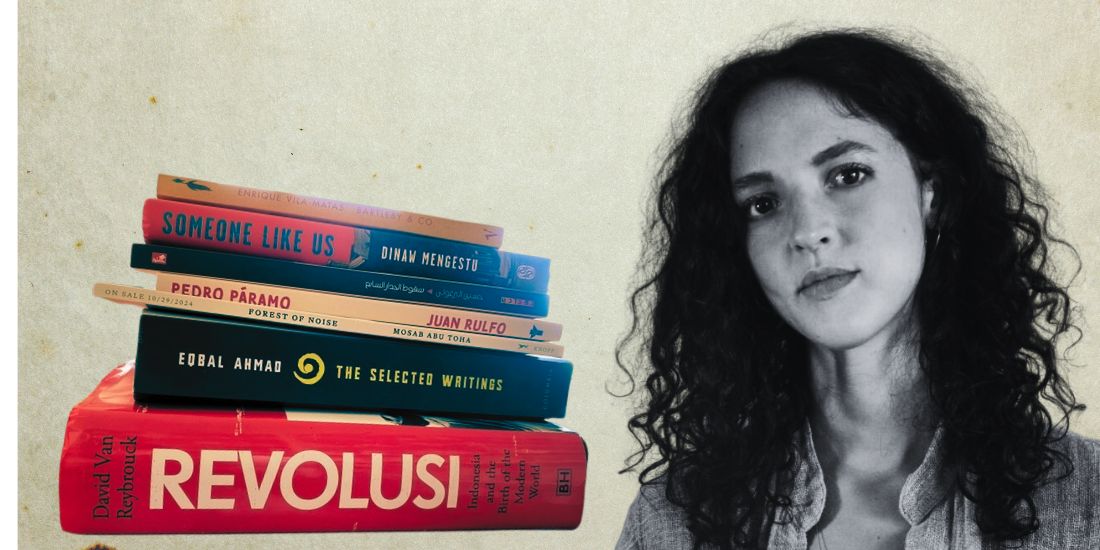

The Annotated Nightstand: What Isabella Hammad Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Enrique Vila-Matas, Dinaw Mengestu, Hussein Barghouthi, and Others

The beginning of Isabella Hammad’s Recognizing the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative begins with a stunning sentence in the frontmatter: “This lecture was originally delivered on September 28, 2023, as the Edward W. Said Memorial Lecture at Columbia University.” Just over two weeks later, Hamas exacted its attack on nearby Israelis, killing 1,139 and kidnapping 251.

Israel’s devastating and stunning military response has killed over 40,000 people in Gaza (including over 16,000 children), as the Israeli government carries out a genocide of the Palestinian people. Violence is escalating in the West Bank, leaving seven hundred Palestinians dead (including a hundred and fifty children).

Israel’s horrifying brutality toward innocent civilians has gripped the world, with powerful protests and a clarion call for Palestinian liberation the globe has never seen before. That all said, Hammad’s lecture is no more or less timely for publication—Palestinians have endured apartheid and violence for generations.

In Recognizing the Stranger, Hammad interrogates Aristotle’s notion of anagnorsis (“a movement from ignorance to knowledge”) and epiphany (two of its meanings, dawn and the emergence of enemy forces, “suggest something appearing beyond the horizon”). She expertly weaves between ancient and modern narratives like those of Oedipus and Odysseus to Ghassan Kanafani’s novel Returning to Haifa and Yasmin El-Rifae’s Radius.

Hammad also discusses her own writing and experiences—including a chance encounter with an IDF deserter named Daniel. His post was at the Gaza fence, given the instructions to escalate non-injuring warning shots at those who came too close to a shot in the leg if they didn’t stand down. After days with no one approaching, he saw a man coming his way.

The point at which he was supposed to shoot the man in the leg, “Daniel could see that he was entirely naked. And that he was holding something out before him,” writes Hammad. “And as he came still closer, Daniel could see he was holding a photograph, and that it was a photograph of a child. He did not shoot the man in the leg. He put down his gun and fled.”

While I don’t normally quote from guest’s titles extensively, these two instances in Hammad’s book merit it. “Empires have fallen, The Berlin Wall fell, political apartheid in South Africa did end,” she writes, “[These] are testaments to the fact that, under the force of coordinated international and local action, Israeli apartheid will also end. The question is, when and how? Where in the narrative do we now stand?”

In her extended afterword, penned in January of this year, Hammad reflects on the words we have just read.

I began the lecture claiming that we can only identify turning points in retrospect. Given the speed and violence with which the cogs are presently rotating, it does feel like we might be in a turning point now: still, we don’t know in which direction we are moving.

You can read Hammad’s initial lecture in the Paris Review.

Hammad tells us about her to-read pile, “A pile of books that I am either in the middle of reading and that I am about to read or would like to read soon. I’m not sure any of them are really bedtime reading, but they do sit in a pile by my bed.”

*

Enrique Vila-Matas, Bartleby & Co (trans. Jonathan Dunne)

One wonderful detail about the accoladed Spanish author of Bartleby & Co is he is a founding Knight of the Order of Finnegans—the beautiful nerds who meet on Bloomsday (aka June 16) in Dublin to read all of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

Vila-Matas speaks about the ritual in an interview :

I’ll meet up with the Knights of the Order in Dublin. At ten minutes to six on the sixteenth of June, we’ll climb the Martello Tower, and we don’t allow anyone outside of our society to be present for the ceremony of acceptance for the newly “ordained” member (the word we use is “recipient” instead of “ordained,” which also means “orderly” in Spanish, and as such is subject to misunderstandings). At exactly six o’clock, we’ll leave the tower and mingle with the rest of the world. I like to climb the tower, because from there I can see the Irish Sea. That sea lifts my spirits.

Dinaw Mengestu, Someone Like Us

Rebecca Makkai, in her review of Mengestu’s novel, writes for the New York Times,

The concrete facts of Someone Like Us: Mamush, a journalist in Paris, is supposed to fly to Washington, D.C., with his wife and young son to spend Christmas in the Virginia suburb where his Ethiopian immigrant mother lives…although Mamush makes it to the airport with plenty of time, he manages to miss his flight.

She goes on,

Those of us who love skewed narratives, slanted truths, destabilized fictions love them best not when they’re just tricks to yank the reader along, but when they speak to the instabilities of reality itself, or of a particular life. Mamush might be hapless, but this book is not; it’s meticulously constructed and its genius doesn’t falter even slightly under scrutiny. Its unreliability is earned, and central.

Hussein Barghouthi, Fall of the Seventh Wall: Psychological Struggle in Literature (سقوط الجدار السابع)

Barghouthi cuts and compelling figure. He was a poet, philosopher, essayist, and wrote many other genres. His childhood seesawed between Palestine, his birthplace and home of his mother, and Beirut, where his father was employed.

Barghouthi wrote poetry often enough as a child that he recited a poem in a contest in high school, only to have the judges express incredulity that he wrote it himself. He studied and earned degrees in Budapest, Birzeit University in Palestine, and University of Washington—Seattle. After receiving his PhD in Comparative Literature, Barghouthi returned to Palestine to teach at his alma mater.

According to Wikipedia, this extended essay attends to “psychological conflict.”

Starting from Brahmanism, the book goes on to include the development and diversification of psychological conflict through time and place, including that of many poets like Mudhafar Al-Nawab and Al-Mutanabbi, and various fictional characters of literature from writers such as Shakespeare and Dostoevsky. It tracks the origins of conflict in human life, cognition and society, and is considered the key to understanding one’s own difficulties, and understanding the rest of his books.

University of Chicago Press distributes two of his works in English translation, including the poetry collection The Blue Light translated by Fady Joudah.

Juan Rulfo, Pedro Páramo (trans. Douglas J. Weatherford)

The most recent translator of Rulfo’s novel, Douglas J. Weatehrford, wrote for our own LitHub about Rulfo and Pedro Páramo, calling the latter “Mexico’s most significant novel.” In his introduction, Gabriel García Márquez describes being uncertain about how to write the “novels in me.” A friend, Álvaro Mutis, brought him a book and said, “Read this shit and learn!”

It was Pedro Páramo. Márquez writes, “That night I couldn’t sleep until I had read it twice. Not since the awesome night I read Kafka’s Metamorphosis…had I been so overcome.” Márquez learned the whole book by heart.

I could recite the entire book front to back and vice versa without a single appreciable error, I could tell you on which page of my edition each scene could be found, and there wasn’t a single aspect of its characters’ personalities which I wasn’t deeply familiar with.

Mosab Abu Toha, Forest of Noise

Barbara Hoffert, in her starred review of Toha’s forthcoming poetry collection at Library Journal, writes,

“No need for radio: / We are the news” says Palestinian poet and librarian Abu Toha, author of the National Book Critics Circle finalist Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear and founder of the Edward Said Library, an English-language public library whose Gaza City branch was recently destroyed. More than any news reporting, this heartbreaking collection makes vividly real the suffering in Gaza and what it’s like to face huge, ongoing loss.

Life is really the “slow death of survival,” notes Abu Toha, adding “We no longer look for Palestine. / Our time is spent dying. / Soon, Palestine will search for us.” Abu Toha can be plainspoken, then turn around with a stark, horrific image that drops like hot coals: “In Jabalia Camp, a mother collects her daughter’s / flesh in a piggy bank, / hoping to buy her a plot / on a river in a faraway land.”

Yet what’s pervasive (and most disturbing) is not the constant thrum of death but the sense of loss—of family, place, memories, continuity, home, and village, with the loss of the past meaning the loss of the future.

Her poignant verdict: “One mourns with Abu Toha as he asks his dead brother, ‘Will my bones find you when I die?’ Highly recommended.” (As an aside, when verifying Hoffert’s pronouns, I found she is retiring from LJ. May she rest on her well-earned laurels after years of LJ criticism!)

Carollee Bengelsdorf (editor), Margaret Cerullo (editor), and Yogesh Chandrani (editor), The Selected Writings of Eqbal Ahmad

Ahmad was a Pakistani theorist and journalist, who engaged in activism during the Algerian Revolution and the American-Vietnam War once he moved to the United States. The jacket copy for this book states,

This work is the first to collect Ahmad’s writings in a single volume. It reflects his distinct understanding of world politics as well as his profound sense of empathy for those living in poverty and oppression. He was a fierce opponent of imperialism and corruption and advocated democratic transformations in postcolonial and third-world societies. A uniquely perceptive critic of colonialism and U.S. foreign policy, Ahmad was equally vigilant in his criticisms of third-world dictatorships.

Noam Chomsky penned the introduction. In a brief video tribute to Ahmad, calls Ahmad

a cherished friend, a leader of protest and resistance, a constant source of incisive, illuminating analysis. There are people who information and knowledge. There are very few who have wisdom, in addition. Eqbal was one of these. The least we can do is to work to expand the rich legacy that he left us.

David Van Reybrouck, Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World

“With 280 million people, [Indonesia] is the fourth most populous nation on Earth, after India, China and the US, and the largest Muslim-majority country. It’s also one of the most overlooked, by western eyes at least,” writes Charlie English in his review of Revolusi for The Guardian. “Relating the story of this place is, then, a mammoth task, requiring a monumental research effort. This is what the Belgian historian David Van Reybrouck has achieved in his superb history, Revolusi.”

English goes on,

The story of colonial greed that unfolds is familiar from British, French and Belgian exploits all over the world. The mercantile project soon became a territorial one, as the VOC [Dutch East India Company aka Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie] took possession of swathes of spice-growing terrain. Sometimes they swapped land with other colonial powers, as in 1667, when they traded the swampy patch of ground on America’s east coast that we now call Manhattan for the far more valuable British-controlled island of Run, a source of precious nutmeg….

Over the next half-century, through the efforts of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army, the Dutch seized the rest of the archipelago. By 1914, the small North Sea nation of less than 6 million controlled the third largest empire in the world.