“Bitterness Incarnate:” Douglas J. Weatherford on Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo

"The text vacillates between presence and absence, between reality and irreality, and even between life and death."

In 1953, the relatively unknown Juan Rulfo (Mexico, 1917-1986) published The Burning Plain (El Llano en llamas), a collection of short stories set in rural Mexico during the first half of the twentieth century. The novel Pedro Páramo (1955) appeared two years later. These innovative works challenged traditional narrative forms, altered the course of Mexican and Latin American fiction, and helped usher in the so-called Boom of Latin American literature that would include renowned figures such as Carlos Fuentes and Rosario Castellanos, from Mexico; and Nobel laureates Mario Vargas Llosa and Gabriel García Márquez, from Peru and Colombia, respectively. A second novel, The Golden Cockerel (El gallo de oro), although penned around 1956, would follow in 1980. Despite this relatively small corpus, Juan Rulfo, with his somber vision of Mexico, captured the imagination of readers to become one of the most celebrated authors in his home country as well as throughout Latin America.

Often considered Mexico’s most significant novel, Pedro Páramo is also that nation’s most translated work of fiction. The already mentioned García Márquez would famously praise the work, proclaiming that it was upon reading Pedro Páramo in the mid-1960s that he finally felt prepared to pen his own masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967, Cien años de soledad). Coincidentally, both Pedro Páramo and One Hundred Years of Solitude will appear soon in highly anticipated Netflix productions, and enthusiasts of both novels are hoping for strong showings. Currently in post-production, Pedro Páramo features three-time Oscar-nominated cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto in his feature-length directorial debut, with Manuel García-Rulfo—a distant relative of the author and star of The Lincoln Lawyer—in the eponymous title role.

*

Juan Rulfo was born in 1917 in southern Jalisco, a region acutely affected by the brutality of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) and the Cristero Revolt (1926-1929). This turbulent period gave birth to modern Mexico and continues to shape the nation’s contemporary society, politics, and culture. Rulfo’s early years were deeply influenced by this period of violence including in 1923, his father was killed in a senseless dispute. Rulfo was six years old. His mother never recovered from the loss and died in 1927 at 32 years of age. As an orphan, Rulfo lived in a boarding school in Guadalajara, the capital of the state of Jalisco, until late adolescence when he moved to Mexico City. Although he would move between these two large cities before settling in the nation’s capital, Rulfo remained deeply attracted to the small towns and countryside of rural Mexico in general and of his home state in particular, and it is this landscape with its often-callous history that so defined his narrative.

*

Despite the significance of Pedro Páramo, most critics would likely agree that the novel has failed to gain the following among English-speaking readers that it deserves. Juan Rulfo is not the only Spanish-language writer to be neglected by English-language readerships, of course, and Rulfo’s relative anonymity among these groups may be attributed, in part, to a crisis of reading in translation in their countries. Beyond this general malaise toward the literatures of other cultures, many observers have wondered if lackluster translations of Pedro Páramo might have contributed to Rulfo’s struggle to secure a loftier position among English-language readers.

Rulfo’s writing is defined by a faith in the ability of diligent readers to discover interpretive possibilities hidden within the disintegration of the novel.Pedro Páramo has appeared in print in English twice before, translated in 1959 by Lysander Kemp (Grove) and in 1994 by Margaret Sayers Peden (Grove and Serpent’s Tail). It is not my intention to disparage previous attempts to make Juan Rulfo’s narrative talents available to English-speaking readers. Indeed, I admire the professional accomplishments of my two predecessors, and I prefer to see my efforts as building upon the work of these earlier individuals. Lysander Kemp (1920-1992), who served as head editor of the University of Texas Press from 1966 to 1975, was a prolific translator whose work on Nobel laureate Octavio Paz is particularly notable. For her part, Margaret Sayers Peden (1927-2020) is one of the most well-known translators of Latin American literature, having worked on such significant figures as Carlos Fuentes and Isabel Allende, among many others. Kemp and Peden deserve praise for their role in making Rulfo available outside of Mexico, and each has moments where their solutions to this author’s challenging text seem inspired.

My favorite example of inventiveness in previous English-language versions of Pedro Páramo comes from Peden. Shortly after the novel opens, one of Pedro Páramo’s estranged sons—not yet named—is led toward Comala, the town that his ruthless father dominated and the one that his pregnant mother abandoned shortly before his birth. This son—now an adult—asks his guide about Pedro Páramo: “Who is he?” The response, in the Spanish-language original, is memorable: “Un rencor vivo.” Peden renders this phrase masterfully as: “Living bile.” Her option, while not fully literal, captures the poetry of Rulfo’s evocation as well as its striking contradiction: Páramo who, although dead at this point in the narrative, lives on in a region still deeply traumatized by his legacy of abuse and loathing.

After completing two drafts of my own translation of Pedro Páramo, I read back through Peden’s version. I was stirred by her reaction to “Un rencor vivo” and realized that my early attempt to capture the beauty and weight of Rulfo’s original was inadequate. I came back to this phrase often over the next several weeks and pondered about two dozen alternatives. I never considered adopting Peden’s words in this instance, however. Not only had I not come up with this possibility on my own, but it seemed clear that her variation was the result of a reading that was very personal. Ultimately, I landed on a solution that I hope readers will find nearly as powerful: “Bitterness incarnate.”

Notwithstanding my appreciation for the efforts of Kemp and Peden, I can say with confidence that Pedro Páramo deserved a new translation. Let me offer here only one example. Rulfo’s novel constantly challenges the reader. It defies comprehension, with confusion and fragmentation central to what seems an unstable fictional world. The text vacillates between presence and absence, between reality and irreality, and even between life and death. At the same time, Rulfo’s writing is defined by a faith in the ability of diligent readers to discover interpretive possibilities hidden within the disintegration of the novel. Facing such a rich fictional source, the successful translator, I believe, must safeguard those elements of the original, no matter how subtle, that are embedded with meaning. Surprisingly, Kemp elided words, phrases, and even whole sentences in his version. Meanwhile, a misstep in the first line of Peden’s translation has undermined that work since it was released nearly thirty years ago. As the novel opens, Páramo’s son (yet unnamed, as mentioned above) explains why he came to Comala. As readers will eventually understand, the place from where this speaker tells his story is essential. In one of the most iconic opening lines of any Latin American novel, this first-person narrator declares: “Vine a Comala porque me dijeron que acá vivía mi padre, un tal Pedro Páramo” (emphasis added). In Peden’s translation, the adverb “here” (acá) is replaced with the adverb “there,” erroneously placing the act of storytelling somewhere outside the anguished town of Comala. My corrected version of this line reads: “I came to Comala because I was told my father lived here, a man named Pedro Páramo” (emphasis added).

Ultimately, the desire to accurately reflect both the letter and the spirit of Rulfo’s fictional universe was fundamental in my efforts to translate one of the seminal texts of Latin America. It has been my pleasure to render this novel into a new English translation, and it is my hope that I have done justice to an author whose enduring literary legacy I admire beyond measure.

__________________________________

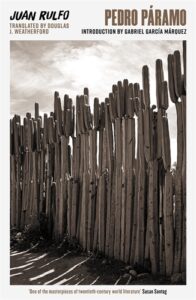

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo, translated by Douglas J. Weatherford, is available from Serpent’s Tail and Grove Press. Translator’s note © 2023 by Douglas J. Weatherford. The book will be available from Grove Press on November 14, 2023.