The Annotated Nightstand: What Elisabeth Houston is Reading Now and Next

A New (at Lit Hub) Series by Diana Arterian

For some time, I ran a series at Entropy in which I would post my own to-read pile along with a guest’s. Entropy folded last year, and Lit Hub has graciously agreed to host this funky little project. Below, you’ll find a writer’s TBR stack, followed by my own commentary on the titles.

*

I first encountered the poet and interdisciplinary artist Elisabeth Houston’s work the way she generally prefers one does: through her performances. In each, Houston assumed the persona of Baby. She had tape over her mouth and wrote a series of questions for the audience on blank pages.

Many years ago, I watched her write who here is racist? on a page. Her eyes scanned as everyone sat, silent, with their hands down—myself included. no one????? she wrote. These engagements pointed to issues of racism, society, and our own complicity so directly (shouldn’t we all have raised our hands?), I was haunted by them for days. When Houston-as-Baby removed the tape and did speak, it was stilted, slow, and deep. Houston read aloud poems that often described the cruelties the character Baby endured in this otherworldly tone. Her poetry about Baby hung on the walls for us to read, which were from third person or Baby’s perspective.

They scrutinized situations regarding trauma, feminism, class, racism, Blackness, sexuality, family, and so much more in powerful verse. While the poems were more urgent in the space Houston had created with her performances, it was clear they operated so singularly that they could and should also be available as a book.

In one poem, Houston writes, “between [baby’s] lips, / there was a heaving universe / which a lion, a goat, or ship could fall into and be lost forever.” So I was thrilled to learn that the collection of these poems, entitled Standard American English, was published by Litmus Press earlier this month.

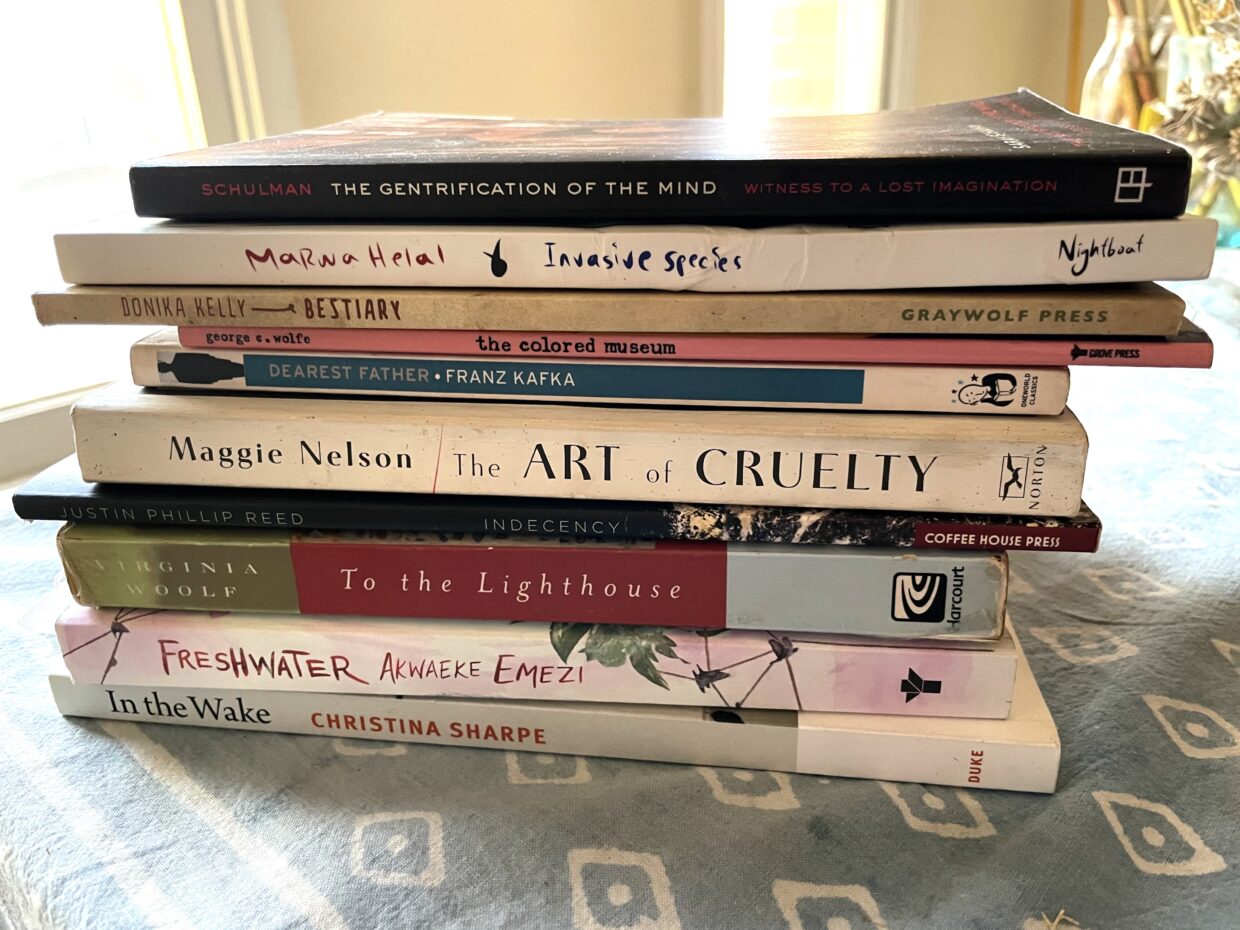

Houston writes on her to-read pile, “It is hard to come up with a universal description of this pile of books, except to say simply and plainly—I love them. Each describes a kind of rupture, a kind of split—between body and mind, child and family, self and nation—and there is a profound ecstasy that comes when literature confronts contradictions and divisions within us and around us.”

Sarah Schulman, The Gentrification of the Mind

The inimitable Schulman provides us with her experiences during the AIDS crisis in the Lower East Side in her memoir. The gritty, queer, interconnected moment between people of all stripes went through a terrible transformation toward uniformity and drive toward traditionalism in the years that followed. In their review in New Statesman, the critic pins it down well: “To her mind, the undigested, unacknowledged trauma of AIDS has brought about a kind of cultural gentrification, a return to conservatism and conformity evident in everything from the decline of small presses to the shift of focus in the gay rights movement towards marriage equality.”

Marwa Helal, Invasive Species

Tyehimba Jess says of Helal’s poetry collection, “Marwa Helal voyages across borders of genre, form, and faith to deliver us beyond simple citizenship and into a higher understanding of our leaving note dreams. These poems are travelin’ papers—inventive, hard fought, sweat swollen passports into an America that bristles with hope through the same mouth that curses it’s home-grown.” The collection moves between verse, prose poems, memoir, reportage, word games, and immigration paperwork with Helal’s own interventions to illustrate the terrible realities that often define migration.

Donika Kelly, Bestiary

Selected by Nikky Finney for the Cave Canem Prize and longlisted for the National Poet Award in Poetry in 2016, Kelly’s first book of poems is known for its descriptions of sexual violence, mythological beasts, love, family, and so much more. In her review, Claire Schwartz writes, “Here, there is no sole patriarchal source. Instead, the generic conventions of the western movie, the cityscape of Los Angeles during the uprising in the wake of four LAPD officers beating Rodney King, the beasts of Greek mythology, the mating rituals of the bowerbird, the tender guardianship of dogs, nineteenth-century poetry, and the erotic connections of gay porn are all absorbed by the poet and remixed as resource.”

George C. Wolfe, The Colored Museum

This mid-1980s play is comprised of eleven brief and sardonic sketches that comment on elements of Black American experiences. These are titled “Cooking with Aunt Ethel,” “The Hairpiece.” One entitled “The Party” has a character envision a party in which “Nat Turner sips champagne out of Eartha Kitt’s slipper.” The New York Times review at the time states, “George C. Wolfe says the unthinkable, says it with uncompromising wit and leaves the audience, as well as a sacred target, in ruins…Mr. Wolfe is the kind of satirist, almost unheard of in today’s timid theater, who takes no prisoners.”

Franz Kafka, trans. Hannah and Richard Stokes, Dearest Father

I am amazed this is the first instance I am learning of this book. It is a letter Kafka wrote to his father in 1919, laying out Hermann Kafka’s emotional abuse. It was forty-five pages long, typed, with a few handwritten pages included. The title comes from Kafka’s salutation: “Dearest Father,” he starts. “You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you. As usual, I was unable to think of any answer to your question, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you.” Kafka apparently gave this letter to his mother to pass along to his father, but she ultimately never delivered it and instead gave it back to Kafka.

Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty

I think of one of Nelson’s pithy quotes from this book often when I write personal nonfiction about “the unsolvable ethical mess that is autobiographical writing.” In the book, Nelson takes on the different ways in which art employs violence, harm, in other words “cruelty,” and its implications in the larger social context. In the rave New York Times review, Laura Kipnis writes, “By reframing the history of the avant-garde in terms of cruelty, and contesting the smugness and didacticism of artist-clinicians…Nelson is taking on modernism’s (and postmodernism’s) most cherished tenets. After all, aesthetic shock has underwritten most of our cultural innovation for over a century.”

Justin Phillip Reed, Indecency

Reed famously won the National Book Award for this first collection of poems that attends to concerns of Black identity, queerness, and the innumerable complications those identities bear up in a country defined by white supremacy and heteronormativity. In an interview, Reed states, “One thing that I would not deny myself while writing this book was to dive deeply into those moments in which I felt my rage and felt somehow betrayed or generally that I had just mismanaged my relationships with people that I was invested in.”

Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

A far dreamier of Woolf’s novels that focuses on a particular family, the Ramsays, and the landscape of their summer home on the water (near a lighthouse). This is of course supremely reductive—I may as well say Mrs. Dalloway is about a day in London after the war. It’s also about creative production, how time invariably brings loss and change. I didn’t realize, however, that this novel actually very much drew from Woolf’s experience as a child and family, and their family’s visits to St. Ives. Woolf called To the Lighthouse “easily the best of my books,” and sold well enough for her and her husband buy a car.

Akwaeke Emezi, Freshwater

Emezi’s debut novel put them on many lists for how remarkable the book is. It follows a character, Ada, from childhood in Nigeria through life in the London and the US. Ada contains many spirits, which ultimately provide the majority of the voices throughout the book. The New Yorker review states, “‘Freshwater’ is alive to the tension between the affirmation of owning a single identity and the freedom and mutability of being multiple. There is something self-defeating about trying to trace a self that is defined by indefinability; one achievement of Emezi’s book is to make that paradox feel generously fertile.”

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake

This is a book I have been meaning to read off and on for years. Every time it surfaces (a friend’s recommendation, a list like this one), I think, I must read this. The book’s chapters, entitled “The Wake,” “The Ship,” “The Hold,” “The Weather,” interrogate the many ways in which enslavement continues to haunt Black diasporic communities. I love that I can quote Sarah Schulman, the first book in Houston’s pile, on Sharpe’s book: “This could have been a one thousand page book, filled with ‘evidence,’ citations and systematic ‘proof,’ but instead it is an earned, slim volume of poetic, intellectual and, in fact, spiritual enactment of struggle.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.