The Annotated Nightstand: What Douglas Manuel is Reading Now and Next

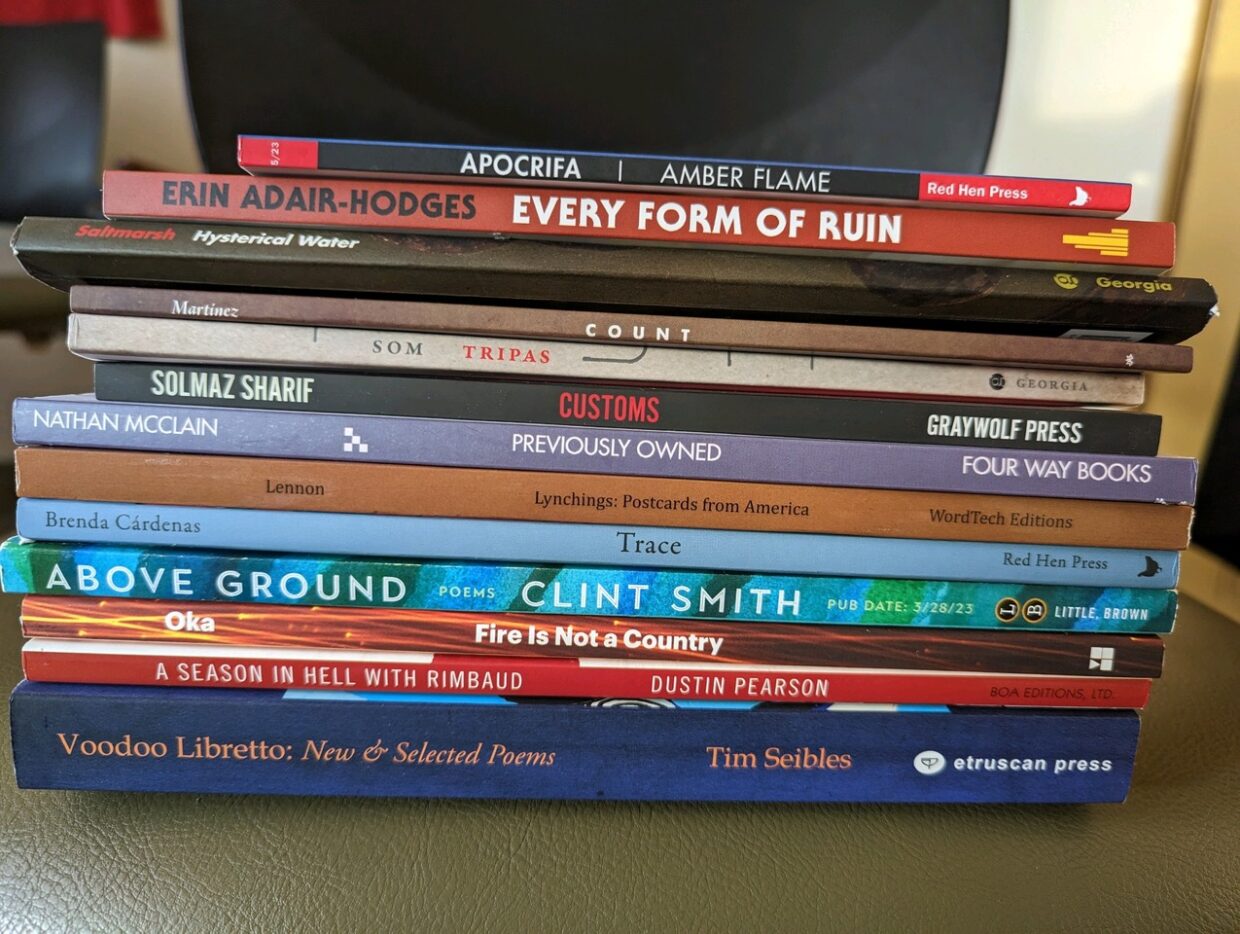

Solmaz Sharif, Amber Flame, Clint Smith and More.

The poet Douglas Manuel’s debut poetry collection Testify follows the topic so many of us (this poet included) attend to first: family. Testify attended to the stark realities of Manuel’s childhood in Anderson, Indiana, a place that once had a burgeoning Black middle class—until the General Motors factory shut down. Anderson was subsequently a community depressed both in finances and morale, and then struck particularly hard by the crack epidemic.

Manuel’s poems in Testify show through first-person lyrical poems what it was like to grow up in such circumstances in which those who used crack were criminals (only later to see those who are addicted to meth and opioids as “sick” or “victims”). Much of this is grounded in the difficult realities of his family, with a father and brother who both did prison bids for selling the drug, and a mother who died depressingly young from MS.

Trouble Funk is a kind of prequel to Testify, and focuses entirely on Manuel’s mother and father. As it describes events prior to Manuel’s birth, Manuel has shed the lyrical “I” entirely, instead approaching scenes as an omniscient god or fly on the wall. The titles of each poem are a nod to his father, a successful DJ in his youth, with titles of songs he loved to spin. We are also given the date of the moment the poem describes (no, “Let’s Get Small” did not come out in 1986).

The dates are vital, for they give us a chronology as we whip between the tender beginnings of Damon and Denise as a couple to Damon’s infidelities and the toxic exchanges that tear them apart. “The song is perfect because he plays / it for her, plays it right then, shines / a light on her” is also part of the life that contains “She screams. He screams. Their scream // the same scream they began with.” Manuel follows this with an accretive list of screams “since the Middle Passage” and ends with “since Civil Rights. // So many screams slicing love.”

Interspersed between the couple’s moments together, we have a sense of menacing police, seeing Roots for the first time, the AIDS epidemic—in short, the environment in which these two people connected. As NewPages states in its review, “Trouble Funk exposes ways Black Love is thwarted but never destroyed by racism, classism, and sexism.” Manuel has taken two people who would otherwise find themselves flattened into caricature by the media and given them room to be living breathing subjects. In his tender poems, they search for love and meaning in a world that tells them again and again they deserve neither. Now and then, blessedly, they find it.

Manuel generously gives quick annotations to each book here, so my own will be largely blurbs and praise. Manuel tells us:

“Considering I’m a new father as well, Clint Smith’s Above Ground has really been resonating with me, and the great Tim Seibles’s expansive Voodoo Libretto: New & Selected Poems has been nourishing and teaching me all year.

Besides these gems, my list this year is compiled of some AWP grabs, Erin Adair-Hodges’ Every Form of Ruin, Nathan McClain’s Previously Owned, Brandon Som’s Tripas, Brenda Cárdenas’ Trace, and Amber Flame’s gorgeous celebration of Black joy and love, Apocrifa. The other books presented here prop up and represent for marginalized communities and sing songs that worm my ears.

Valerie Martínez’s Count is an ecopoetic epic of water; Lester Lennon creates a new poetic form and reminds us of the horrors of lynchings; Hannah Baker Saltmarsh places the maternal body in historical context by exploring the term hysteria; Solmaz Sharif teaches America about itself as only she can, with incisive wit, critique, and restorative lyrics; Dustin Pearson’s speaker searches for his brother with Rimbaud’s aid, and Cynthia Dewi Oka’s Fire is Not a Country is one of my favorite texts from last year. I just want everyone to pick it up, learn from it, and delight in the heights of blazing harangue and symphony.”

Amber Flame, Apocrifa

Publishers Weekly says, “The expansive and formally inventive second collection from Flame (Ordinary Cruelty) considers the cornerstones of romance—doubt, surrender, grief, resolution—through poems about hunger, exploration, and forbidden fruit… The strength of this collection lies in the structural ingenuity of its poems; Flame uses poetic license to preface each with translated definitions of love-adjacent words from dozens of languages. Her source languages span the globe and time itself, from Inuit, Tshiluba, and Urdu to the extinct Latin and Yagan. The varied forms here, from sonnets, epistles, sestinas, and cinquains, allow for dual interpretations and narrative fluidity. These entries need to be consumed slowly to be best appreciated.”

Erin Adair-Hodges, Every Form of Ruin

Shara McCallum says of this collection, “Cast often through fairytale and myth, Erin Adair-Hodges’s new collection audaciously examines a contemporary experience of womanhood. Every Form of Ruin is a scalpel, exposing various forms of gendered violence, the vicissitudes and joys of wifedom and motherhood (‘momming’ as the poet brilliantly neologizes), and the power of sisterhood and of claiming the self in all its multitudes.

There is so much in the craft of these poems equally to admire and revel in, including Adair-Hodges’s seemingly effortlessly inventive turns of image, line, and phrase. Her tone and the voice of these poems is also a wonder, at once irreverent, funny, biting, and downright sad. While the poems square themselves against ruin, they are actually resplendent, coming to us as they do, from ‘a country in which the poet is the only citizen so, also, its queen.’”

Hannah Baker Saltmarsh, Hysterical Water

I’m reveling in the length and generosity of poets blurbing other poets. This is a recurring theme in this post. Here is Elizabeth Arnold’s blurb for this debut: “Many poems from Hannah Baker Saltmarsh’s stunning first book, Hysterical Water, are documentary. The facts and found language that make up these poems are fascinating by themselves, and there are plenty.

But as you keep reading, it becomes clear rather quickly that these facts and found language are largely meant to concentrate the lyrical language that, strung across the breadth of the book, acts as its spine. Saltmarsh’s personal experience, as a mother, as a woman in the world, drives everything. Moments of profound change, of visionary transport, lift the weight of political, historical, sociological detail. In a poem about where a mother can and cannot nurse, Saltmarsh’s own baby nursing—earlier described as a jigsaw of ‘stopping and starting, intermittent dreaming, sleeping, demanding, the spastic calm, the fringes of lashes like flapper bangs’—suddenly metamorphoses into ‘a sapling, latched to the infrastructure of my leafy breasts.’ Such astonishing swerves into transformative perception are the product of ‘merging the confessional with the archival.’ It’s a winning combination.”

Valerie Martínez, Count

“I cannot think of a timelier book than Count,” Rigoberto Gonzaléz writes. “And I wouldn’t trust such a book from a poet who’s not as attuned as Valerie Martínez to the urgencies of environmental issues and their inextricable bond to social justice. Martínez has shaped a poetics that weaves the ecological with the mythical with the personal.” Juliana Spahr says Count is “a book that stuns with its attentions and its wisdoms as Valerie Martínez captures so much that is beautiful in this world, as she notices so much that is at risk.”

Brandon Som, Tripas

Som was the winner of the 2015 Kate Tufts Discovery Award for his book The Tribute Horse, which the committee describes as “riotously alliterative and full of assonance… We can hear the hiss of the waves through the soft consonant repetition. Irresistibly, the poetic line stows away in the procedural memory—which is the part of our brains that remembers music no matter how old we become.”

Because I always love to see when people blurb books in the same pile, here are Rigoberto Gonzaléz’s words on Som’s latest collection: “Brandon Som celebrates his Chinese and Mexican ancestries by amplifying not collision but coalition—a cultural partnership that’s existed in the Americas for generations, though seldomly encountered in poetry. At this vibrant intersection of language, ethnicity, and identity, inventive imagery is borne and so too a surprising lens that leaves us awestruck by Som’s rich poetic landscape and multivalent story.”

Solmaz Sharif, Customs

Library Journal in its starred review of Customs writes, “Following the National Book Award finalist Look, Sharif’s second collection is alternately scathing, funny, resigned, and transcendent. Her poems interrogate the bonds of social performance and the bureaucratic language of power… The poems grapple with belonging, what it means to exist inside and outside—of a nation, language, place, or time.” I love how LJ gives a “verdict,” not shielding the fact that reviews are, generally, grounded in judgment (like a jury in a courtroom, even). It states, in all caps: “VERDICT Blistering in its clear-sightedness (‘No crueler word than return./ No greater lie’), this collection offers a fierce, beautiful closing that dares to imagine ‘a beckoning, a way.’ A bold and uncompromising book with virtuosic emotional range; highly recommended.”

Nathan McClain, Previously Owned

Anything praised by Diane Seuss is going to turn my head. Her words on this collection: “The opening poem of Nathan McClain’s Previously Owned operates like the legend of a map, a key to the book’s existential topography. The poem’s presenting subject is a Roman sculpture of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot, or ‘not pulling / rather, about to pull.’ McClain addresses the self via the second person, and draws in the reader, too, as observer: ‘and here you / are, looking,’ witness to the boy’s ‘insistent grief.’ ‘And what // have you learned from / standing here so long examining pain?’ Previously Owned exists in this incremental space—the about to pull, the almost, the grief, the tenderness, the examination, and the distance.

It’s a masterstroke in a masterful collection, in which a speaker of a nuanced intelligence and lush interiority reflects upon the American landscape, its pastoral and judicial and historical duplicity entwined with racial alienation and violence. McClain has written a collection of sculptural artfulness—through which the thorn of grief thrums still.”

Lester Graves Lennon, Lynchings: Postcards from America

David Mason says of Lennon’s collection, “From his first lines about survival in black churches, Lester Graves Lennon casts a cold and passionate eye on American violence. His poems are richly textured and raw and real with enduring music. The ‘postcards,’ a profound and terrifying sequence about lynchings in America, become an undeniable record, beautifully written, horribly real. But the generous, unflinching work gathered in ‘Postcards from America’ also reminds us of the joys of family, and the hope that the arc of history does indeed bend toward justice. These are poems by a man who has lived and thought and felt with abiding grace.”

Brenda Cárdenas, Trace

Manuel’s pressmate also has a book out this month! Valerie Martínez, whose collection Count is also in this pile, says of Cárdenas’ collection, “This remarkable collection migrates from outward to inward–ekphrastic poems charged with ars resistencia to biographical poems of childhood wonder, teen rebelliousness, middle age dreams. Throughout, we are immersed in the ‘morphology of dream, the moonmilk of words.’ Cárdenas loves language–each turn of phrase radiates the power of the word to mean, resonate, and transcend. These poems, like a ‘flatbed full of cempazuchil,’ light the way.”

Clint Smith, Above Ground

Smith was a guest on this column in March for this very collection. I wrote, “As June Jordan states in her brilliant essay on Phillis Wheatley ‘The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America,’ ‘America has long been tolerant of Black children, compared to its reception of independent Black men and Black women.” This was published almost a decade before the murders of Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, the many Black children who are victims of police violence and whose names have made it into the national news. But Jordan’s notion that there is greater tolerance of Black children than Black adults in this country still stands. This is the humming terror behind many of the poems in Above Ground—what will happen to Smith’s children through their childhoods, adulthoods, and how, above all else, to illustrate they are loved.”

Cynthia Dewi Oka, Fire Is Not a Country

Jenny Zhang, the beloved poet and fiction writer, says of Oka’s collection, “Reading Cynthia Dewi Oka is an EXPERIENCE. In Fire Is Not a Country, the devotional is alive and freed from those who have abused it. Reverence is as honorable as irreverence. Sorrow is subterranean and always fighting valiantly to come to the surface. Ghosts live vicariously through the living. The ancestors are calling and calling and calling. Sometimes images precede meaning and sometimes meaning creates images. Memory ‘is long / and bendy.’

This book is full of prisms to behold and textures to touch and so the rewards are manifold and delicious. How to describe something that is best experienced in the bodies we are in? ‘I have just begun to love / the little knives of which I’m made.’ I kept this book by my pillow for weeks. Night after night, I returned, wanting to experience it again.”

Dustin Pearson, A Season in Hell with Rimbaud

The remarkable poet Raymond Antrobus says of Pearson’s latest collection, “‘You can lose your brother to Hell/ and still be happy inside your house,’ begins one of Pearson’s striking and unforgettable poems. Pearson is at once metaphysical and allegorical. While summoning Rimbaud’s symbolism poetics, he creates a voice uniquely his own, with questions of brotherhood, performative masculinity, and the horrors and vulnerabilities of our mortal bodies. There are many rooms to open in each of Pearson’s poems.

A Season in Hell with Rimbaud is a rich and thorough collection. Each time the speaker’s brother is addressed, a history of violence and traumas that the brother has been subjected to in Hell is simultaneously summoned. But is hell another dimension, an internal space, an external space, or is it right here on earth? Pearson keeps reminding us that, ‘The house has many rooms,’ and we find meaning inside and out of each real, imagined and metaphysical space. What a poetic accomplishment this is!”

Tim Seibles, Voodoo Libretto: New & Selected Poems

Cherise A. Pollard writes in her review of Seibles’ collection, “In Voodoo Libretto, play is kaleidoscopic. There are so many ways that Seibles indulges in serious play — child’s play, sports, word play, imagination, dreamtime and flirtation. For Seibles, play pushes the boundaries of our expectations, challenges us to reconsider our beliefs. From self-proclaimed class clown to adult trickster, Seibles’ imagination invites the reader into investigative distraction. In several poems, playing football and basketball is a way for the speaker to connect with his buddies, and a pathway to masculinity.”