The Annotated Nightstand: What Diane Seuss is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Frank O'Hara, Evie Shockley, Monica Rico, and More

I start this post with the confession that I’m relatively late to the Diane Seuss party—it was only after she won the Pulitzer Prize and NBCC in Poetry for frank: sonnets that I opened the door with the thumping bassline behind it. The ways in which the collection was wonderfully stunning was twofold. First, that the poems were incredible—like some inner voice I had never met but knew well was finally speaking up.

Second, that such a compellingly weird collection (deservedly) won such illustrious prizes. If you follow literary Twitter (why call it the other thing?), you may have seen the recent kerfuffle in which someone posted a screenshot from frank and questioned not only if the poem was a sonnet but argued that perhaps it wasn’t even a poem. Many many many writers came to Seuss’ (and poetry’s) defense. As one user put it: “I hate how easy it is to troll poetry Twitter, but it’s also v cute how much we all clearly love Diane Seuss.”

Seuss eventually responded with remarkable grace by locating poems by the person who posted the invective and replied, “we are very different writers, but I read you with openness and admiration for your own grief and struggles.” A couple of weeks later, Seuss wrote a generous thread on sonnets as a living form and the lineage she drew upon for the collection. She writes,

The foldout in the center of [frank], about my son’s addiction, is a visual and even physical representation of what fourteen lines can, and must, hold. I couldn’t have written [frank]without the sonnet, whose origins and endless variations I respect and love beyond measure.

So we have a new collection from this American treasure—Modern Poetry, just out from Graywolf. As I read Modern Poetry, I mostly asked myself, “Can this woman write a bad book?” Or, really, “Can this woman write anything other than a stunner?” Seuss continues to approach her art with rigor blended with a rare wildness. While the format of the poems may look relatively staid, it provides a sort of tabula rasa upon which Seuss piles powerful images that are difficult to dismiss. In short: the book is very hard to put down.

It’s challenging to quote these poems, as they generally involve an extended emotional ride. But, luckily, Seuss’ prowess at simile and metaphor is equally undeniable. We have a bloody tampon left in the woods “like the scat of a wild animal.” Or when she imagines running into her father who died when she was a child, his apparent disappointment at seeing Seuss now: “It was as if God looked upon creation and wondered / at its atrocities. How, God thinks, could I / have fucked up so badly, but keeps it to himself.”

But what makes Seuss’ work remarkable is she moves on from provocative images in ways that are just as surprising. In one poem, a “famous lounge singer” brought out of a hotel in Vegas “on a stretcher with a broken / lightbulb in his ass.” Her call after this visual: “Be that guy. / Don’t be Jesus, be the Shroud. / Don’t be the savior, be the stain.” The way in which Seuss interrogates longing, nostalgia, memory, loss, relationships makes plain she is someone who has been around the block enough times that we should pay attention.

Her gift to her readers is she delivers her poetry with an appropriate urgency considering that these are often the experiences that define a life. “My stories are caskets filled with black feathers, // the lids pounded shut with railway spikes,” she writes. As long as she continues to share these stories, we should all consider ourselves lucky.

Seuss tells us about her to-read pile,

There are books in my stack that I’ve read before, even books for which I’ve written blurbs, books I’ve partly read, and books I’ve wanted to get to for years. I rounded-up these ten because in the reading and re-reading, all will teach me about experimentation with language, which will help me, I hope, with the project on which I’m now working, tentatively called Althea, of short poems that experiment with language in new ways (for me). I’d like to have e.e. cummings in there, but I don’t have one of his books. I stuck the old textbook, Modern Poetry, in there because it’s the first book of poems I ever saw, and I was too young to read it. Maybe I still am. It ended up titling my next book, Modern Poetry, a shout-out to the book’s origin story. The candy cigarettes on top are a wink at my previous book, frank: sonnets, as is the wonderfully tattered copy of O’Hara’s Lunch: Poems. If you know you know.

*

Frank O’Hara, Lunch: Poems

In 2014, it was the fiftieth anniversary of arguably the most famous collection by the New York School poet during his lifetime. Dwight Garner wrote on the half-century mark for the book in the New York Times, writing,

America in 1964 was straining to break out of black and white and into color, and ‘Lunch Poems’ was part of the brewing social drama. The directness of O’Hara’s voice was a tonic. Taxis are preferable to subways, he declared in one poem, because “subways are only fun when you’re feeling sexy”….This is a book worth imbibing again, especially if you live in Manhattan, but really if you’re awake and curious anywhere. O’Hara speaks directly across the decades to our hopes and fears and especially our delights; his lines are as intimate as a telephone call. Few books of his era show less age.

Maynard Mack, Leonard Dean, and William Frost (editors), Modern Poetry

In this 1950 volume, the editors write an introduction with several subtitles. Under “A Philosophic Problem,” they write,

Modern poetry in general has the reputation of being esoteric and obscure; but the human problem which is at the heart of much of the best of it is not at all hard to understand. Stated in its broadest general terms, this problem might be said to be the contrast or conflict or disparity felt by any intelligent, sensitive person today between experience measurable or describable in the terms of physical science, and that immeasurable meaning—of whatever sort—which permeates experience in the form of value. For modern man, this problem is necessarily acute: we can split the atom—that is a physical, scientific matter; but splitting it merely faces us with the question of what to do about the bomb—which is a political or social or moral or ethical or even metaphysical matter, and much less easy for us to handle. Yet both matters are tied up inseparably in the same atom—the scientifically graspable world on the one hand, and on the other hand the same world as it exists in terms of esthetics or ethics or religion or psychology.

(As an aside, I’m kind of obsessed with the font in this edition.)

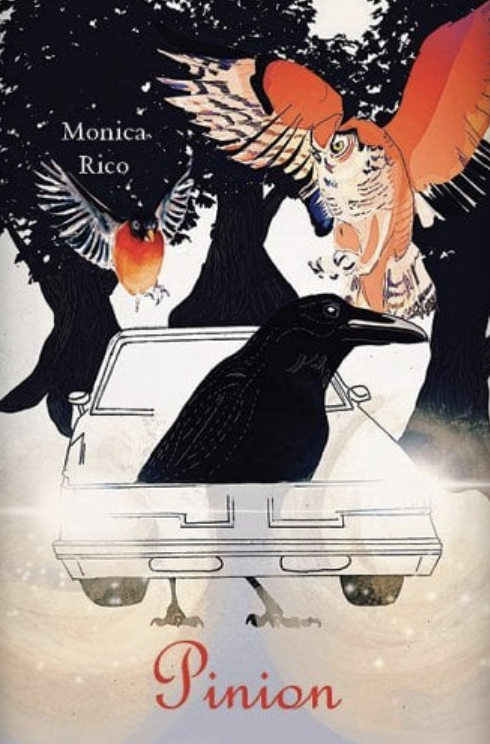

Monica Rico, Pinion

This forthcoming poetry collection is reviewed by Steven Leyva in the Washington Independent, where he writes,

Even as the extraordinary tensions of quotidian lives are highlighted by attending to the lives of Mexican Americans in Michigan, none of the possibilities of spell-making or the miraculous are lost in syntax….The lines bring to mind the kind of working-class attention that Philip Levine brought to his poems about Detroit, but with a different attention to synthesis. Here, everything that feels so physical, present, and muscular in the syntax also makes us see the weariness of something constructed to be shipped or driven somewhere else.

Rico won the 2021 Levis Prize in Poetry, and judge Kaveh Akbar states, “Inside Monica Rico’s Pinion, centuries grind together inside a pinch of yeast, across slain soldiers and a pigeon dusted with coal. It’s such a dazzling braid, illuminating (and complicating) civic histories with familial mythologies.”

Evie Shockley, semiautomatic

Christopher Spaide writes in his LA Review of Books review of semiautomatic,

If Shockley has a Muse, it’s Prince, the chameleonic musician she invoked in earlier books and mourns in her new book’s first poem: “{Prince, U R Forever In My Life}.” Shockley’s virtuosity, like Prince’s, is less a gift of making from scratch than a genius for making it new. Amid her wardrobe changes and hairpin stylistic turns, Shockley’s “I” can seem slithery, impossible to pin down: her most consistent figure (again, like Prince’s) is her “you” (or “U”), insistently questioned, refused, seduced, decried, defended. Shockley trains her perfect ear not only on past traditions but on her own writing, in real time: phrase by phrase, even phoneme by phoneme, you can catch her listening for every rhyme, accidental allusion, and double entendre.

Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing (trans. Susan Sellers)

In a recent interview with David Naimon on Between the Covers, Cixous spoke in a way that’s akin to her written word. At one point, she stated,

When we’re afraid, we’re afraid of death always. I’m afraid of water, I’m afraid of being drowned, etc. It’s very strong… Montaigne, our great philosopher writer who used to say that que philosopher c’est apprendre à mourir, to think in philosophical ways is the only way to learn how to die. He was terrified by death. He would think about it all the time. When you read the essays, as Shakespeare has done, because he read Montaigne, during the two-thirds of his fantastic unique work and way of reflecting on all human faith, suddenly he thought no, maybe it’s not really learning to die, maybe it’s learning to live. He realized that they were both the faces of the same approach to life-death. You cannot think of one without the other. Of course, there’s another influence that suddenly permeates life, because when you start aging, which starts very, very, very—I’m hesitating, should I say “early” or “late?” I want the truth.—Then gradually, death comes nearer and nearer and nearer, and you will realize that death isn’t only death, we have nothing to say about this, it doesn’t exist. What we have to say is about what do we do with life with what is given, with time, how do we transform time in creation?

Bianca Stone (editor), The Essential Ruth Stone

For years poet and artist Bianca Stone, along with her brother, husband, and small staff, have acted as stewards of Ruth Stone’s legacy. They created the Ruth Stone House nonprofit to restore the late poet’s house and making it a Vermont landmark as well as develop programming such as letterpress book arts, workshops, a podcast, the journal Iterant. In an interview with the independent Vermont weekly Seven Days, Stone states, “Ruth Stone was someone steeped in what [Harold] Bloom called ‘the art of memory.’ She was melding history and metaphysics in her writing. She was (ironically) sincere in her irreverence towards sincerity — which you can see in such lines as the opening to ‘The Excuse’: ‘Do they write poems when they have something to say, / Something to think about, / Rubbed from the world’s hard rubbing in the excess of every day?’ She pulls apart emotion like unweaving a basket. It’s horrifying and amazing to witness in a poem. What I wanted to expose in this collection was her almost violent dry wit, that supernatural honesty. That was her way in to grief and suffering.”

Courtney Faye Taylor, Concentrate

“Taylor’s arresting and powerful debut excavates and commemorates the life of Latasha Harlins, a Black teenager killed by a Korean shop owner following a false accusation of theft—a killing that served as a catalyst for the 1992 uprising in Los Angeles,” writes Amy Dickinson in her starred review for Library Journal,

Taylor’s collection explores, in part, the tension between Asian American and Black communities in the United States, as well as the country’s complex interplay among race, sexual violence, and erasure. The collection also memorializes a young life, foregrounds tremendous care between elders and children (as in the brilliantly moving opening poem, “Arizona?”), and employs an inventive fractured style.

Can we all pause for this remarkable “verdict” though? “Simply put, one of the best books this reviewer has read in the last twelve months.

Dora Malech and Laura T. Smith (eds.), The American Sonnet: An Anthology of Poems and Essays

In the Times Literary Supplement, Anahid Nersessian writes for her review of this anthology,

If the sonnet is, as Jonson said, a “tyrant’s bed,” it is also a lectern, and here is what it wants you to learn: small freedoms are possible within a situation of constraint, but they are probably trivial or doomed (death will be proud). Because it is relatively rule-bound (it should have about fourteen lines, a solid metre and reliable rhymes, a change of tone or heart just past its middle, and a kick of eloquence at the end), the sonnet offers itself as the ideal forum in which to explore those freedoms and materialize that constraint. It is a swiftly self-annotating exercise that presents itself as both instance and elucidation, a little song (from the Italian sonetto) that never fails to drive home what it means to sing.

William Carlos Williams, Selected Poems

In her lecture “Dr. Williams’ Heiresses,” poet Alice Notley gives a playful mythological ramble of her literary progenitors. She states, “Poe was the first one, he mated with a goddess. His children were Emily Dickinson & Walt Whitman—out of wedlock.” Eventually Notley gets to her generation of women writers: “They came to indulge in a kind of ancestor worship—that is they each fell in love with a not too distant ancestor… the one named Alice Notley fell in love with her grandfather, William Carlos Williams.”

Eventually Notley begins to talk about what, exactly, made Williams her poetic “grandfather.” She writes,

[Williams] made it so I could write about the kids, or not always about, but just include the kids. It’s because of Williams that you can include everything….We still haven’t caught up with what Williams meant by the variable foot, which has to do with scoring for tone of voice, which is part of your music & your breath, but maybe even more. Variable foot is maybe about the dominance of tone of voice over other considerations—I do my poems this way ’cause I talk from here—haven’t you ever talked to anyone? I’m not an oracle or a musical instrument or a tradition or a stethoscope or a bellows or even a typewriter: I am a tone of voice.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, Selected Poetry (ed. Catherine Phillips)

It’s always a treat to have a long-dead, established writer in a stack. Diving into the Wikipedia wormhole of Hopkins’ life, I learned that the future Jesuit priest grew up in a high-church Anglican household. Thus perhaps it is unsurprised that, as a teen, Manley Hopkins dabbled in asceticism. In one case, he claimed people didn’t need nearly as much fluids as was generally believed. To test his theory, Manley Hopkins tried to go without for a week. His tongue eventually turned black and he passed out at school.

Manley Hopkins wrote his first (known) poem at the age of sixteen. I was equally amazed to learn his brother, Lionel, was British Consul at Yantai, became an renowned expert on Chinese language (both archaic and colloquial), and had a remarkable collection of oracle bones now housed at Cambridge University Library.

Gertrude Stein, Selected Writings

In her introduction to her own edited collection of Stein’s work Every Day Is To-Day: Essential Writings, Francesca Wade writes about Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and its overnight success for the nearly hexagenarian author that precipitated a lecture tour in the US:

This was, [Stein] decided, a chance for doubting readers to learn how to read Stein from Stein herself; to turn attention away from the gossipy Autobiography and back to her older, notoriously “difficult” work, and make the case for its importance and, crucially, for its pleasure. “If you understand a thing you enjoy it,” she told a bemused reporter, “and if you enjoy a thing you understand it.” Over the course of six lectures, repeated in packed halls at universities, clubs and galleries in thirty-seven cities, she set out to challenge prevailing assumptions and convince readers that her work required no prior knowledge or intellectual framework; that there was no secret code to be deciphered, no key to the riddle. All that was needed, she repeated, was an open mind.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.