The Annotated Nightstand: What Daniel Saldaña Paris is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Gustav Flaubert, Yiyun Li, Francesca Wade, and Others

The Dance and the Fire, the new novel by Daniel Saldaña París and translated by Christina MacSweeney, is broken into three parts, each devoted to one of three enmeshed childhood friends whose tethers have frayed over time. Now in their thirties, they find themselves living in their home an hour outside Mexico City, the city of Cuernavaca—a place now defined by flames. “We’ve all become accustomed to the stories of people being unable to breathe and asthmatics dropping like flies while tongues of fire lick every corner of the state,” one explains.

The three are Natalia, Erre, and Conejo. While they all expected bright futures defined by artistry and intellectualism, each is living a circumscribed life (Natalia in a largely loveless marriage, Erre divorced and living in his childhood home, Conejo caretaking for a blind and cranky parent). As teens, they had blurred between romantic and sexual in pairs, undeniably connected yet ambivalent.

But now Natalia is married to an esteemed-but-aging painter decades her senor whose distasteful grasps at remaining relevant drives her to largely try to avoid him. Unbeknownst to her, Natalia’s husband calls in a favor—the Ministry of Culture will host a dance performance of her creation. What began as a frustrating marital gesture becomes a summons for Natalia. She wants to create a grander piece about the city and its purpose beyond the common or capitalist.

The first portion of The Dance and the Fire is “a sort of diary” into which Natalia pours the captivating results of her research that will coalesce into the performance. This includes dance epidemics in the sixteenth century, witch trials in Sweden a hundred years later, the life and work of choreographer Mary Wigman (specifically her uncanny Hexentanz—”witch dance”).

While Natalia’s sense of purpose tightens, Erre and Conejo drift. After nights in his childhood bed staring at the ceiling, Erre spends his days haunting the city streets. He is hounded by a chronic pain so unbearable he is soon popping pills in a fruitless attempt to banish it. Erre and Natalia bumble into some sort of romantic reconnection, wary yet compelled.

And Conejo cares for his father, a relic of revolution, blind and abandoned by his wife. The brilliant Conejo, often stoned in his room, reads conspiracy theories about Cuernavaca and its fires—calling Natalia to share them now and then. Conejo is in a kind of distant, tender love with both Erre and Natalia, the beautiful “holy trinity” the three of them were as teens.

While this sounds like a narrative defined by angst, its characters those you want to take by the shoulders and shake to snap them out of it, Saldaña París somehow manages to give us three people defined by their humanity and nuance rather than their states of arrested development. In telling The Dance and the Fire through three voices, the story comes at us in a compelling bits and pieces defined by the often-pinhole perspectives of each (Natalia: research-driven, Erre: narcotic haze, Conejo: borderline agoraphobic).

The stakes, too, are there in the background of these personal dramas—the city seemingly on the brink of explosion, its inextinguishable fires a dread-inducing bass line that won’t let up. And of course the novel is barreling toward Natalia’s performance, what a random civilian will call “the first dance plague since the Middle Ages.”

Saldaña París tells us about his to-read pile (along with a list!):

This nightstand pile is a mix of everything. It includes borrowed books, others I just bought, one I bought years ago and never read, and one I found in a basement in Switzerland. There’s poetry, novels, biography, non-fiction, and criticism. Books in the three languages I read comfortably (without a dictionary at hand), and books in translation.

I know I’ll abandon some of these midway through. Others I’ll finish in two days—and maybe forget I ever read them. It’s a perfect snapshot of my reading habits at any time: always split between too many things, always wanting to do more than I can, and always coming back to the places that made me who I am:

Flaubert: A debt in my reading culture. I’m reading it in French to stay in touch with the language.

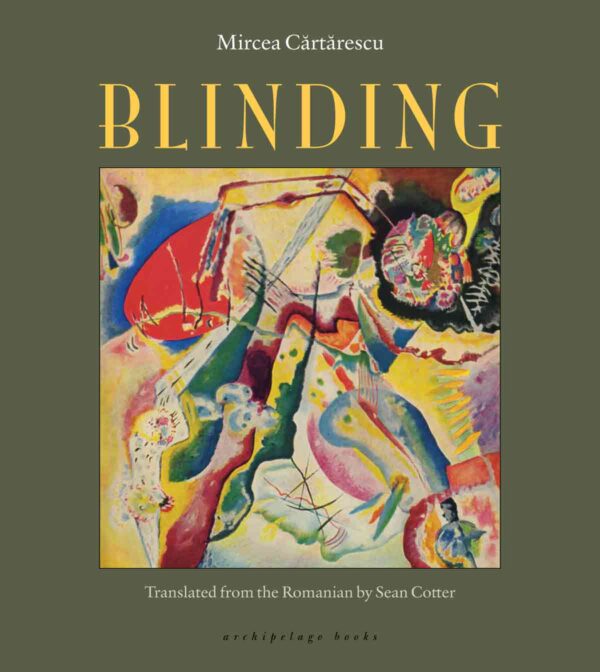

Cărtărescu: I bought this one years ago, after finishing Solenoid. I have to be in the right mood to read Cărtărescu, but he never disappoints me.

Gertrude Stein’s biography: I was a Cullman Center fellow with Francesca Wade and have been obsessed with this book since way before it existed. Wade is one of the most talented biographers out there, and Stein is a fascinating character.

Paulina Flores: Young Chilean writer. Anagrama wunderkind. I loved her short stories and this is the first novel of hers I’m reading.

Ricœur: I read “Oneself as Another” recently and even though I dislike his style, I’ll keep reading Ricoeur for his ideas.

Hang Kang: I got this one at the Strand and started reading it on the plane. I cannot put it down.1. Yiyun Li – I just brought this back from a trip to NYC and it is one of the non-fiction books I look forward to the most this year.

Merwin: I’ve been reading Merwin for many years. I have a t-shirt with a few lines from his poem “Berryman,” given to me by my friend Brenda Lozano. This book I borrowed it from my friend Kiki, and I want to read it next.

*

Gustav Flaubert, L’Éducation sentimentale (Sentimental Education)

Aaron Peck writes in the Times Literary Supplement,

Published in 1869, Sentimental Education portrays the coming of age of its central character in the years before France’s Second Empire, an ironic hero whose self-absorption prevents him from any meaningful engagement in life. His involvement in the Revolution of 1848, which led to the first modern democratic election with universal male suffrage, dwindles in comparison to his failed attempts to seduce Madame Arnoux….

Flaubert meant the book to be a “moral history” of how the inner lives of his generation were shaped and disillusioned by contemporary events.

Mircea Cărtărescu, Cegador I: El ala izquierda (trans. into Spanish by Marian Ochoa de Eribe) (Blinding: The Left Wing, trans. into English by Sean Cotter)

Translated from Romanian (Orbitor I: Aripa stângă) into Spanish (Cegador I: El ala izquierda) and English as Blinding, Volume I: The Left Wing, this is the first of three Orbitor volumes (next is The Body, followed by The Right Wing).

The jacket copy of Ochoa de Eribe’s Spanish translation describes Blinding as “the monumental butterfly-shaped trilogy unanimously considered Romanian Mircea Cărtărescu’s masterpiece. A visceral exercise in literary self-exploration about feminine nature and the mother, a fictional journey through the geography of a hallucinated city, a Bucharest that becomes the setting for universal history.”

Francesca Wade, Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife

This much-anticipated biography is hitting U.S. bookshelves in the fall—but it has been getting plenty of love in the U.K. Luke Kennard at The Telegraph calls it :a masterpiece of biography.” He writes,

Wade shows a great sensitivity to the morality of biography writing, and the tendency to sensationalism, historical or contemporary. She’s an exceptional writer, able to draw out the legend, the contradictions and the reality in a fully coherent, dizzyingly comprehensive triptych: Stein was a genius, and also a real and often quite difficult person, in life and after.

Paulina Flores, La próxima vez que te vea, te mato (The Next Time I See You, I’ll Kill You)

The title of this novel is literally translated to “The next time I see you, I’ll kill you.” Its jacket copy states,

With a voice somewhere between Violeta Parra and Bad Bunny, Paulina Flores paints a portrait of a city, a generation, and its distinctive characteristics in this tragicomedy. Admired by her compatriot Alejandro Zambra and selected by Granta as one of the best Spanish-language writers, she is now considered one of the most innovative authors on the contemporary Spanish-language scene.

Paul Ricœur, Tiempo y Narración II: configuración del tiempo en el relato de ficción (trans. Agustín Neira) (Time and Narrative, Vol. II)

Ricœur is largely known as the French philosopher who made subjective interpretation of texts a viable pursuit (we have Ricœur to thank for: phenomenology + hermeneutics).

Originally entitled Temps et Récit (Time and Narrative in English), in this volume, as the jacket copy to the English translation states, “Ricoeur argues that fiction depends on the reader’s understanding of narrative traditions, which do evolve but necessarily include a temporal dimension. He looks at how time is actually expressed in narrative fiction, particularly through use of tenses, point of view, and voice.”

Han Kang, We Do Not Part (trans. E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris)

Lydia Millet writes of the recent Nobel Prize winner Kang’s novel in the New York Times,

For those of us struggling to grapple with the overwhelming flow of news about current conflicts in other countries—including South Korea, where political turmoil is painfully reanimating the iron-gloved ghosts of its past—and the authoritarian threat unspooling in our own, We Do Not Part is a chilling reminder of the terrible invisibility of people and events that are removed from us in space and time.

Yiyun Li, Things in Nature Merely Grow

Li’s recent memoir describes her shattering reality after “two sons, full of promise, took their own lives,” writes Kirkus. The review continues, “[Li] notes that her older son died on the very day she put down a deposit for her new house in Princeton, the kind of coincidence that would seem unbelievable in fiction, on which she concludes, ‘Life…does not follow a novelist’s discipline. Fiction, one suspects, is tamer than life.'”

W.S. Merwin, The Folding Cliffs: A Narrative of Nineteenth-Century Hawaii

Merwin famously moved to Hawai’i in the 1970s and spent decades planting palms decimated by colonial extraction (since his death, his home has become a conservancy). Publishers Weekly writes of this The Folding Cliffs, “His sprawling new novel-in-verse (based on historical facts) unfolds a complicated, suspenseful, true story of natives, colonials, rebels and leprosy in 19th-century Kaua’i, spread over seven chapters of forty one-page sections.”

You can read a portion here.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.