The Annotated Nightstand: What Catherine Lacey is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Jen Calleja, Tezer Özlü, Georgi Gospodinov and More

Möbius strips are a kind of mindfuck you can touch. It’s three-dimensional, just a strip of paper with a single twist joined into a loop—something a child could make. But, somehow, it’s a kind of two-dimensional plane that can break your brain. If something flat traverses the strip, it returns to its point of origin flipped. Also, it goes on forever. Catherine Lacey’s new book The Möbius Book plays on this both in content and form. The volume is a tête-bêche (head to tail), with a novella starting from the front.

A memoir starts, flipped, from the back cover. They meet at their endpoints. This is more than simply a twee move, but rather a larger gesture toward the ways in which fiction and life intersect—how the stories we invent often are grounded, in some way, in experience or internal fixations. In both, teacups make important appearances, as does faith, religious belief, and heartbreak. There are men who build women up in both so they can tear them down all that more quickly. It’s more than merely inspiration—it’s the uncanny twinning between life and art.

The novella takes place over Christmas night, contained to the equivalent of a one-act play in the character Marie’s bleak apartment. Marie and her old friend Edie are caught between a jolly ruckus on the street and a puddle of blood oozing into the hallway from the apartment next door that Marie is trying to convince herself she didn’t see. Both women are unmoored after heartbreaks of different kinds. The humming throughline is the ways one can be and feel out of control—in love, belief, sex, victimhood. Marie exploded a marriage she never really wanted to enter in the first place with her infidelity. Edie is just on the other side of an emotionally abusive relationship. The slow-drip of emotional terror Edie has endured—and feels uncertain she can even call abuse—is given a sharper edge alongside a final image of physical abuse its victim is no less uncertain what she can claim. Explicit physical traces or no, it can feel hard to believe what you allow yourself to endure.

The memoir describes the fallout of Lacey’s divorce from her emotionally abusive husband. The portrait of their relationship comes in bits and pieces, but quickly accretes to one predominantly defined by gaslighting and emotional sabotage. “I began to believe him,” she writes, “and yet that belief brought with it a strict obedience to this person who, it seemed, created me.” Her ex breaks up with her via email when they’re both home. I love Lacey’s friend who laughs, gobsmacked, saying, “People get fired with more dignity.” Lacey probes her shock and early attempts at feeling, feeling better even. But also the many things she put faith into beyond this marriage—other romantic relationships, her religious beliefs of childhood, her disordered eating in the loss of that faith.

Essentially (though hardly as trite): how did she get here? One of the most moving elements of the book is all the friends who come and go as the pages flip, the many people who, in variety equal to their number, try to help Lacey cope (one gives her bricks to throw at a wall, another tells her to read Seneca). At one point in the novella, Marie asks Edie, “A relationship is an act of faith—it’s a kind of magic or experiment, isn’t it?” The notion of faith (what we pour our faith into, how we contend with its rupture) is much of what Lacey attends to within these two endlessly looping and interconnected narratives.

Lacey tells us about her to-read pile:

None of these books are related to anything I’m working on; I keep that stack of books elsewhere in the house. I’ve been in the process of moving my library, checked luggage by checked luggage, to Mexico City. I’ve almost got everything here now, but for years I haven’t really had the luxury of having stacks of unread books around at home.

But recently I moved almost 200 pounds of mostly unread (or want-to-re-read) books home. I did an event in London with Jen Calleja so I’ve been meaning to read this book for roughly a year. I just started it last night. Pink Slime was translated by my friend Heather Cleary, but also I’ve met Fernanda and she’s so cool.

Time Shelter I’ve been meaning to read since it came out. Madeleine Thien is a writer I adore, and also a friend. She was in Mexico City earlier this year and brought me this galley. I feel horrible when I get a galley and don’t manage to read it until a while after finished copies are out but that happens almost every time I am given a galley.

The Louis Althusser was a recommendation from Rachel Kushner when we met briefly in South Carolina last year. I started it in December but it felt too intense to read in winter, so it’s been lurking beside since then. I can’t read much at night, but when I’m in the best phases of life, I read for an hour in bed in the morning before doing anything else.

*

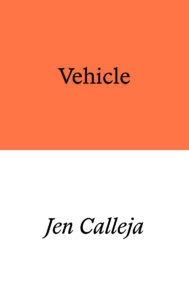

Jen Calleja, Vehicle: a verse novel

The jacket copy for this novel in verse reads, “In a time when looking into the past has become a socially unacceptable and illegal act in the Nation, a group of scholars are offered an attractive residency to allow them to pursue their projects. When the residency transpires to be a devastating trick, these Researchers go on the run, and soon discover that their projects all relate to one major event: the Isletese Disaster.” Recent Annotated Nightstand guest Kate Briggs calls it “Bold, bracing, brilliant.” You can read an excerpt here at Lit Hub!

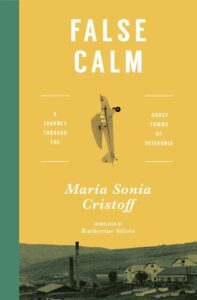

María Sonia Cristoff, trans. Katherine Silver, False Calm: A Journey Through the Ghost Towns of Patagonia

It’s been a while since there have been so many great books in translation in a pile! Sean McCoy writes of False Calm in Los Angeles Review of Books: “These stories might well be rooted in the history and remote regions of the American West. But for María Sonia Cristoff, a prominent writer in Buenos Aires, inspiration springs from the Argentine South, where she was born and raised. In the opening pages of False Calm (Transit Books, 2018), which first appeared in Spanish in 2005, she homes in on the one trait all the people and places she covers have in common: ‘[I]solation is present in everything I have ever read about Patagonia. […] I returned to write an account of this eminently Patagonian characteristic.’”

Jeremy Gavron, Felix Culpa: A Novel

“Felix Culpa is a collage novel in that the bulk of its text is made up of lines lifted from other novels,” writes Colin Barrett in The Guardian. “The plot of Felix Culpa is framed as a mystery: when the novel opens, Felix, a young thief who was sent to prison after accidentally killing an old woman, has died in mysterious circumstances a short while after his release. A writer in residence at the prison begins to investigate Felix’s death, encountering a young woman he was in a relationship with and finally the shepherd for whom he once worked.”

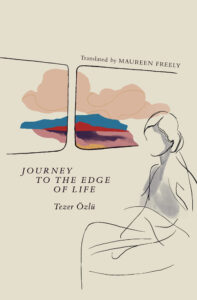

Tezer Özlü, trans. Maureen Freely, Journey to the Edge of Life

Publishers Weekly writes of Özlü’s novel, “Two weeks after the death of a lover, the unnamed 40-year-old narrator sends her child to Stockholm and embarks on a journey to visit the graves of the writers who influenced her. Lacking ‘a steady job or a proper place to live,’ she crisscrosses the continent from Berlin to Vienna to Prague and several other cities, keeping a travelogue along the way. Her voyage is conceived, she writes, as a ‘pilgrimage’ to the resting places of those ‘who have made me who I am’: Franz Kafka, Italo Svevo, and Cesare Pavese.”

Fernanda Trías, trans. Heather Cleary, Pink Slime

In its starred review, Kirkus explains this novel longlisted for the NBA in translated literature “begins with a suffocating sense of doom and doesn’t let up from there. The unnamed narrator, living in a port town in an unnamed country, describes the aftermath of a destructive algae bloom that’s choking the life out of the area: ‘Under each unbroken surface, mold cleaved silent through wood, rust bored into metal. Everything was rotting. We were, too.’…The townspeople who have chosen to remain are forced to endure power outages and food shortages, with many only able to eat a processed food called ‘Meatrite’—the ‘pink slime’ of the title.”

Georgi Gospodinov, trans. Angela Rodel, Time Shelter

Listed in the New Yorker’s “Best Books of 2022,” they write, “In this antic fantasy of European politics, narrated by a fictionalized version of the author, an enigmatic friend of his designs ‘a clinic of the past,’ which soothes Alzheimer’s patients with environments from a time they can still remember. As the treatment gains prominence, feverish nostalgia grips the continent… [Gospodinov] cunningly drawing attention to the violence that the past wreaks on the present” Time Shelter won the Booker in 2023.

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, trans. Robin Myers, We Are Green and Trembling

Laura Pensa writes in World Literature Today, “Readers, you will emerge from this novel with dirty hands. The distance from the fire that ravages and devours the mountains will shorten, and I can guarantee you will feel somewhat responsible for the disaster. Critique—or the rewriting of official history—exists but is not linear, that is, it does not content itself with mechanically reversing the relationship between villains and heroes, nor is it about attacking the great myths head-on.”

Andrés Felipe Solano, trans. Will Vanderhyden, Gloria

In Asymptote Journal, Liliana Torpey writes, “The narrative [of Gloria] primarily follows her over a single day in Spring of 1970: before, during, and after witnessing Argentine singer Sandro’s performance at Madison Square Garden—the first Latin American artist to take that stage. This is the day, the narrator tells us, that ‘Gloria was Gloria for the first time.’ We are then given momentary glimpses into other stages of her life, including childhood, marriage, infidelity, motherhood, and career changes—but the focus returns always to this eternal present: Gloria.”

Madeleine Thien, The Book of Records

In her interview with David Naimon, Thien describes an inspiration for a structure (“the Sea”) in her speculative novel: “There’s a Du Fu poem where he, during the horrific civil war that he lives through in the 8th century, where he says he wishes he could build a mansion of 10,000 rooms and whoever would need shelter could find a rest there, a place there, a place to breathe again. And I did think of the Sea as that. Initially it gives refuge to Lina and her father, but because it becomes their home, she also becomes the one who gives shelter, conversation, exchange, dialogue.”

Louis Althusser, trans. Richard Veasey, The Future Lasts Forever: A Memoir

The French political theorist Althusser famously murdered his wife and, deemed mentally unfit, avoided a trial and was assigned a guardian. “Althusser, calling himself a ‘missing person,’ claims to be writing his memoir from this ‘non-place.’ He writes…from beyond the grave: He writes buried alive,” writes Alice Kaplan writes in her excellent 1994 Los Angeles Times review. The “editors’ forward, like the introduction to a very good mystery tale, frames what follows with a statement of the basic facts and with provocative questions for the reader: ‘How is it that such a story can move into the realm of madness, yet its author remain so aware?’”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.