The Annotated Nightstand: What Caren Beilin Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Isabella Hammad, Stephen King, Lana Lin, and Others

Caren Beilin’s new novel, Sea, Poison, like her much of her other work, attends to the terrible realities of the medical industry and the personal effect this has on people. (She wrote about how her IUD triggered terrible rheumatoid arthritis in her memoir Blackfishing the IUD, and fictionalizes, in part, her experience of arthritic feet in Revenge of the Scapegoat). Of course, Beilin’s writing is about so much else, and it never feels tired to read her work about such a potent topic that impacts so many.

This also doesn’t imply the book is depressing or a tear-jerker—quite the opposite. Beilin, wizard that she is, manages to make you laugh even at the darkest of scenarios. Like when the protagonist Cumin Baleen realizes maybe her recent ex has joined a cult in which everyone serves an ailing man, she thinks, “I wondered if in the American medical system, in the nursing and in the American aging system, this is what’s actually required to get any help with the toilet. Start a cult.”

The protagonist’s name, Cumin Baleen, is a clear joke. Of course, Beilin is writing about herself! But is she? The thin veil between fact and fiction sets your head spinning, as Cumin is told her best chance to treat her rheumatoid arthritis medicine and get her fingers unclench from their claw shape—to continue writing her novel—she needs to get an eye exam. And then the eye exam leads to a surgery.

But the laser singes her brain. Then she can barely write a sentence. Sea, Poison is circuitous, mimicking the experience of mystery ailments, the bureaucracy of medical care, and its endless wormholes. But these problems aren’t consigned to the medical sphere. People talk past each other perpetually in the novel, many talking at Cumin but not to her. When people talk at you, they’re not thinking about optics. They often reveal more than they mean to.

The center around which the novel circles, what Cumin was trying to write about before her brain injury made it impossible, is one of the medical industry’s darkest secrets: sexual abuse exacted by OBGYNs and forced hysterectomies. When people are perhaps more vulnerable than any other moment and that vulnerability is, horrifically, exploited. World War II is a shadow of the book, as its title is drawn from Shusaku Endo’s short story The Sea and Poison about a Japanese doctor late in the war performing experiments on captured Americans under the guise of medical knowledge but its purpose is far darker.

Beilin also meditates on OuLiPo, how Anne Frank hiding from Nazis was, perhaps, the ultimate form of writing with a constraint. Cumin’s brain is singed—anything she writes is certainly borne from constraint. The fact I have struggled to give you an unblurry picture of this amazing and short novel illustrates Beilin’s mastery of the written word. I tip my hat to Publishers Weekly, which manages to accomplish where I’ve failed a third of the space. They write in their starred review, “Beilin employs a host of narrative tricks to reflect [Cumin’s] unsettled state, including sudden time shifts, a dose of metafiction, and Ouilpian constraints…Above all its tricks, this rewarding and uncompromising novel is distinguished by its deliriously wild writing (the moon is described as ‘bright as a hexed white plate.’)”

Beilin tells us about her to-read pile: “I told my rheumatologist I’d read his favorite King novel by the time of our next appointment, which is coming up. Dorothy mailed me their new ones and the Lana Lin is immediately capturing me. Otherwise, I’m stackless, stuff in storage, housesitting at writer/journalist Ben Mauk and artist/photographer Carleen Coulter’s place in Cleveland; he tells me the books here capture undergrad-2014, along with whatever’s been very recently acquired (we’re all new to Cleveland). I looked through their shelves and found a few books that I’ve refused to read out of pursuing them directly, because my intentions are so strong around them it’s like I’ve already read them, and I know that they’ll need to be met, not pursued. Some crystalline, obvious incident. The one with only a black binding is an ARC of Dyer’s Zona (Ben tells me he reviewed it in grad school), which I’ve been waiting unsuccessfully to meet crystallinely since 2012.”

*

Hilary Plum, Important Groups

“In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups. Between April and December 2024, I was writing a long poem,” writes Plum on her Substack. “Like many of you I haven’t known, I keep not knowing, how to think and to live this past 15 months, in which we were conscripted to bear witness as our government…funded and armed a technologically massive assault on a small densely populated civilian area, funded and armed a genocide in Gaza. Once again protests were widespread and that didn’t matter or at least not enough.”

Stephen King, Pet Sematary

“‘Pet Sematary,’ with its downright silly title, [is] inspired by a place on the edge of a Maine forest where children had gone over the years to bury their dead dogs and parakeets,” writes Christopher Lehmann-Haupt at the New York Times in 1983. (I’ve always wondered if “Pet Sematary” is like how Led Zeppelin wanted to avoid being called Leed Zeppelin if they spelled their name correctly.) Lehmann-Haupt comes around, writing, “What has always made Mr. King so effective as a storyteller is his instinct for subtly exploiting the unconscious hostility and consequent guilt that men and women feel in the routine of living with each other and raising their children.”

Geoff Dyer, Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

Sukhdev Sandhu writes at The Guardian, “Two-thirds of the way into Zona, his characteristically singular book about Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), Geoff Dyer declares: ‘There are few things I hate more than when someone, in an attempt to persuade me to see a film, starts summarising it.’ Doing so has the effect of ‘destroying any chance of my ever going to see it’. It’s a surprising assertion – though less so if you’re familiar with Dyer’s books which, whether they’re about jazz, the first world war or DH Lawrence, go out of their way to fuse form and content in arresting fashion – because Zona is one long movie summary, a shot-by-shot rewrite.”

Isabella Hammad, Recognizing the Stranger

Hammad’s rigorous and vital book has been in several to-read piles. “I first heard Hammad speak a year ago, at an event that many of us Arab writers now view, in hindsight, as a similarly revelatory moment—a prelude to the one that would upend everything,” writes Abdelrahman Elgendy at The Nation. “The event was the Palestine Writes Literature Festival, held at the University of Pennsylvania in September 2023. There, I listened to Hammad discuss her latest novel, Enter Ghost…But what I recall most vividly from Hammad’s conversation was her discussion of a slightly adjacent theme: how to write from a place of exile when one is denied a homeland.”

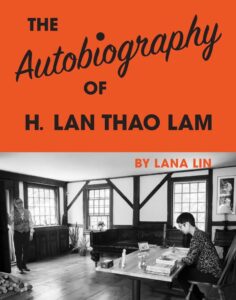

Lana Lin, The Autobiography of H. Lan Thao Lam

“Taking inspiration from Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, filmmaker Lin debuts with a bold ‘memoir’ in which she narrates her partner’s life story from her partner’s point of view. In a meditative register, Lin (as Lam) recalls the pair’s first meeting in New York City, then plunges further back into Lam’s adolescence,” writes Publishers Weekly in its starred review. “The couple’s joys and challenges get equal airtime, with odes to their creative chemistry bumping against harrowing recollections of Lin’s breast cancer treatment.”

Georges Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces (tr. John Sturrock)

I recently found a vital Internet (I like to lean into being a luddite and this is what I call a website): The Complete Review. It is a compendium of reviews for any number of titles, its own review, and a catalog of links, similar titles. I’m a little embarrassed I only discovered it recently, considering I’ve been writing this column for over three years (!) and it’s such an amazing resource. Anyway, via The Complete Review, here is a quote from the 1998 Washington Post review of Species of Spaces, “If you’ve been tempted to try Georges Perec’s masterpiece Life: A User’s Manual and found its length daunting, you might prefer to look into this volume of his selected writings.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.