The Annotated Nightstand: What Anton Hur Is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Han Kang, Irenosen Okojie, Siang Lu, and Others

Considering the spooky time of year has begun (which Drew Broussard and I spoke about here at the Lit Hub Podcast!), Bora Chung’s Midnight Timetable feels apt as a book to kick off the season. Anton Hur, Chung’s translator and an author in his own right of the July title Toward Eternity, is our guest today. Walking around in the dark with only a flashlight for company for hours is tough, even in the best of circumstances.

Our narrator is charged with doing just that, as a nighttime security guard at “the Institute,” a building that holds materials connected with otherworldly events. It sounds as if one door has bird is flapping wildly behind it (we learn more about that later), phones are discouraged (even when turned off, “ghosts like communication devices”).

The narrator’s sunbae (senior colleague) gives everyone the rundown. Don’t look behind you if you hear a sound, make sure the doors to each room are locked, if a nondescript man tells you not to go somewhere, listen. Even with these clear directives, eerie events abound, which the sunbae relays to the narrator. She describes stories in which the blind can see, the dead don’t stay dead—and how, if the haunting didn’t come from the building itself, some ghostly remnant ended up in the Institute’s walls. Perhaps the most eerie recurring detail in these stories is how a phone will ring, a calm voice in the earpiece implying death is imminent. “Would you like us to deliver your shroud along with your coffin?” it asks.

The larger themes of Midnight Timetable are about death and loss, yes, but how frequently greed and cruelty sprout from this fertile earth. A son exploits his mother his whole life, then is cursed by a boundless desire for a handkerchief—her one requested object to be included in her cremation that didn’t make it into the fire. One man, drawn to the widow of his dead best friend, kills her when she wants to break it off, “So perhaps it was a little surprising how displeased the man was when the dead woman began to visit him.”

For the soft readers out there like myself, this book was eerie without making it hard to lie down alone in the dark. In its starred review, Publishers Weekly states, “With a bone-dry wit and biting allegorical edge, expertly captured in Hur’s translation, Chung turns the haunted-object trope into a vehicle for radical empathy and sharp critique.”

Hur graciously annotated his books in his to-read pile! He writes:

Dana A. Williams, Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship

I will read anything by and about Toni Morrison. For example, I read Miss Chloe by A. J. Verdelle a couple of years ago and really enjoyed it. Ever since I was a middle school student, which was when I first read Beloved, I have always felt like Toni Morrison gives me permission to write and be an author. In bed I read using my Kindle, and Morrison’s words have been lulling me to sleep these past few weeks.

Seong Haena, Honmono

Everyone is reading this short story collection in Korea. It hasn’t been translated yet, but I believe the Literary Translation Institute of Korea just ran a translation contest using one of the stories and there are some English summaries of it available online. I do like to keep abreast of what’s trending in Korea, although what’s popular in Korea isn’t always popular in English translation—many horror stories abound.

Han Kang, The Fruit of My Woman

I’m really glad I don’t have to read Han Kang in translation, although I do like Deborah Smith’s take on her prose. Deborah did a translation of the title story of this collection, for those who are curious. Han Kang’s short stories are sharp and satisfying and very subtly textured, which is so satisfying to read and makes me want to translate them.

Heo Su-gyeong, At a Station That No One Remembers

It’s a play on words—the title can also be translated into “at the station where no one remembers.” Like, none of the people in the station can remember. If I translated this collection, I would have to think about which to use. The late Heo Su-gyeong led the most extraordinary life. She was a much beloved poet, of course, but she also retrained as an archeologist later in life and would go on digs in Mesopotamia and other parts of Western Asia.

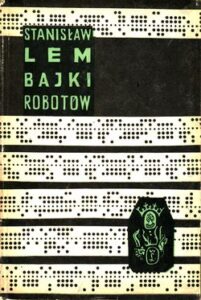

Stanisłav Lem, Fables for Robots (tr. into Korean by Bora Chung)

Bora Chung is also a translator, and she is also my translator, as she translated my novel Toward Eternity into Korean. My translator, Bora Chung, also translates from Polish and Russian, and she is the perfect translator for Stanislav Lem, who is kind of a World Grandfather of Science Fiction. I’m glad I get to read his work in Bora’s Korean translation, just like I’m glad I get to read Pablo Neruda translated through Chong Hyon-jong. Bora gives her translations such bite and verve.

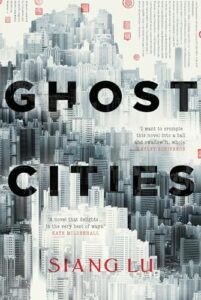

Siang Lu, Ghost Cities

Siang Lu is a very cool, very hilarious Australian author, and Ghost Cities just won the Miles Franklin Award. He’s won so many awards for this book that the cover is now mostly awards stickers at this point. I’m extremely happy for him and hope his book finds a publisher in the US (you would think it’s a no-brainer for an editor to pick up, but I guess intellectual prejudice against the outer rim of the empire runs deep).

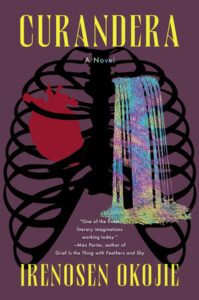

Irenosen Okojie, Curandera

I met Irenosen as a fellow judge for the Dublin Literary Award last year, and she was just so cool and smart and funny, which in itself is funny because you would never guess such a normal-seeming person would write such stunningly surreal prose and imagery. I am absolutely loving Curandera’s language and just the way it is written, it’s really different and unapologetic and draws the reader to itself instead of coming to the reader. As a Korean translator, I can relate.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.