The Annotated Nightstand: What Anne Fadiman is Reading Now, and Next

Featuring Tony Tulathimutte, George Eliot, C Pam Zhang, and More

Anne Fadiman’s 2008 collection At Large and At Small: Familiar Essays employed a form beloved by Charles Lamb (the Romantic Era thinker for whom Fadiman has confessed of harboring a crush). Merve Emre writes at the New York Review of Books that the “familiar” in familiar essays is “familiarity concerned the relationship triangulated between the essay’s writer and its reader—a relationship between friends.” Fadiman carries this ethos into her latest collection, Frog and Other Essays.

At first glance, the collection seemed to be a paean to rejects. The ancient hulk of a printer. The mail-order tadpole that stuck around for almost two decades as an adult frog, cared for but not much cared about. Hartley Coleridge remembered “for two things and two things only: he was the son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and he was a disappointment.”

As I read on, however, I realized Frog was a meditation on things loved, uneasily. There is that frog who hung out too long, Hartley Coleridge living in the shadow of a parent, the a late-1980s printer purchase that would induce sticker shock on even the stouthearted making it all the more difficult to let it go. But also teaching class but online during COVID-19 lockdown, the tragedy folded within the tale of the South Polar Times.

Frog is written by someone who is besotted by life and its perpetual gifts, even if in prickly or limp or heartbreaking packages. Each piece is a portal into life, knowing, and the self. The pieces are studded with details I love, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge clinging to Charles Lamb’s coat button to continue a conversation—“Lamb took out his penknife and cut off the button.” Sam Anderson in his foreword to Frog, “Fadiman helped me to believe, deep down in my ordinary bones, that literature doesn’t have to be exclusive, or rare, or institutional. It can be personal, for absolutely everyone…Your own little ordinary life isn’t an obstacle—it is all that literature was ever about.”

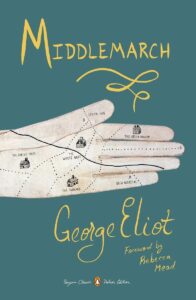

Fadiman tells us of her to-read pile: “I had not realized quite how heterogeneous my nightstand reading was until I transformed the off-kilter heap into a tidy tower. It’s got fiction and nonfiction; books from three continents; books by a friend, a former student, a current colleague. There are 187 years between the oldest book (Nicholas Nickleby, in a gilt-stamped edition that belonged to my husband’s great-grandmother) and the newest (The Wall Dancers). The most important commonality is that none of these are work books. I’m not teaching them; I’m not writing about them. Bedtime reading—in a dark room, with a reading light around my neck and the aforementioned husband sleeping beside me—is purely for pleasure. I’ll be reading nine of these books for the first time and one for the third. Back to Middlemarch I go, though since my Riverside paperback is more than half a century old, it may terminally delaminate before I get to page 613.”

*

Tony Tulathimutte, Rejection

Jia Tolentino says of Rejection at the New Yorker, “Not until I picked up Tony Tulathimutte’s ‘Rejection’ did I realize how fun it could be to read a book about a bunch of huge fucking losers. It sucks for them, the inept, lonely, self-obsessed, self-righteous, self-imprisoned protagonists of these linked stories, but it’s a thrill for the sickos among us, the king being Tulathimutte, who gives loserdom its own rancid carnival.”

Leila Guerriero, A Simple Story: The Last Malambo

Dan Pipenbring writes at The Paris Review, “Imagine a cutthroat dance competition with no sensationalism or vanity, a challenge so detached from spectacle that the media hardly covers it: that’s the national Malambo contest, held for centuries in the Argentinean village of Laborde.” Pipenbring goes on to explain the Malambo “demands rigorous training and peak physical condition, and its practitioners embrace an almost priestly regime of asceticism and self-denial.” Read an excerpt of A Simple Story at The Believer.

Vita Sackville-West, The Edwardians

This 1930 novel by the woman largely known as Virginia Woolf’s lover was a bestseller. She clearly drew from her own wild life and family to craft the narrative. The jacket copy reads, “this glittering satire of Edwardian high society features a privileged brother and sister torn between tradition and a chance at an independent life. Sebastian is young, handsome, moody, and the heir to Chevron, a vast and opulent ducal estate. He feels a deep love for the countryside and for his patrimony, but he loathes the frivolous social world his mother and her shallow friends represent.”

George Eliot, Middlemarch

At The Guardian, Robert McCrum calls this beloved 1871 novel a “masterpiece.” “Subtitled ‘a study of provincial life’, the novel has a didactic realism that’s a world away from Vanity Fair or Great Expectations. Indeed, Middlemarch looms above the mid-Victorian literary landscape like a cathedral of words in whose shadowy vastness its readers can find every kind of addictive discomfort, a sequence of raw truths.” McCrum continues, “Few of Eliot’s characters achieve what they really want, and all have to learn to compromise.”

Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby

Dickens’ third novel and, as with many of his others, delivered in a tantalizing serial. The full title is The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Containing a Faithful Account of the Fortunes, Misfortunes, Uprisings, Downfallings, and Complete Career of the Nickleby Family, and catalogs just that. When the family patriarch dies, Nicholas, his mother, and sister are thrown into financial destitution. They find themselves dependent upon a heartless uncle bent on humiliating the family further while claiming his generosity is what’s keeping them afloat.

Cynthia Zarin, Estate

Publishers Weekly states, “Caroline, the narrator, has recently separated from her husband, Daniel, in New York City, and fallen inconveniently in love with her longtime friend Lorenzo, an Italian who himself is involved with two other women. Zarin reflects Caroline’s head-spinning emotional state in the novel’s form, a choppy series of digressions and vignettes, most of which are addressed to Lorenzo.”

C Pam Zhang, How Much of These Hills Is Gold

According to Martha Southgate at the New York Times, Zhang “dismantles the myth of the American West, or, rather, builds it up by adding faces and stories that have often been missing from the picture.” Southgate goes on, saying the novel “is an arresting, beautiful novel that in no way directly mines another. But by invoking [Western] tropes, she reimagines them for thousands of forgotten Americans of different races and gender orientations; her American West is no longer populated only by the all-white, predominantly male cast of characters who, we’ve been told, created it.”

Megan Marshall, After Lives

Brian Renvall writes at Library Journal of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer’s memoir-in-essays, saying that, throughout, “Marshall uses her biographer’s tools—interviewing witnesses, examining documents, checking memories against facts, and contending with separation from one’s subjects. What is gleaned from the assembled leavings is a form of truth, getting to a person’s core—in this case, the core of Marshall herself.”

Yi-Ling Liu, The Wall Dancers

“In her full-length debut, journalist Liu dissects and dismantles monoliths, highlighting and explaining the seeming contradictions and fatalistic predictions that fuel most conversations about China’s adoption, creation, use, and control of technology,” states Kirkus. “Into a milieu of weaponized tariffs and proprietary technology, the author injects essential context for China’s famed ‘Great Firewall’ and profiles five individuals who have lived beyond its constraints.”

The Selected Letters of John Updike (ed. James Schiff)

Luminary Vivian Gornick writes at The Nation, “The tone of voice in which these letters are written is singularly overriding; because of it, regardless of the content or the recipient (whether young or old, famous or obscure), they all sound pretty much alike. As the years went on, this voice achieved ever greater ease with itself. It became open, amiable, self-assured, wonderfully lucid, and brilliantly organized; it was also emotionally impenetrable…At all times, we are in the presence of a writer who never loses sight of his gift for composition.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.