The Annotated Nightstand: What Andrew Sean Greer is Reading Now and Next

A Series by Diana Arterian

The unplanned irony of Less, Andrew Sean Greer’s satirical novel, is that the protagonist feels he’s in the shadow of his former lover, a Pulitzer-prize winning poet. The irony here is Greer won the Pulitzer for Less in 2018. In Less, we follow the titular Arthur Less as he flees his problems (an ex’s wedding, a floundering writing career), which are compounded by a looming fiftieth birthday. Less travels the world under the guise of different literary events and residencies and classes, only to have things, ultimately, fall into place for him.

Now we have the sequel, Less Is Lost, in which Greer casts his roving protagonist across the United States with a science writer and his pet pug as travel companions. Despite the countless shenanigans Less creates and endures, Greer manages to have him remain a lovable nincompoop to the reader. As Marlon James says of the book, “Only Arthur Less could be both frustratingly stuck, yet on the move. Let loose, yet totally lost. Full of wit, but without a clue. And while he runs from himself, finds himself at the same time.” Less and his absurd adventures are a means for Greer to give us what we so often come to literature for, the deeper issues that plague so many—love, loneliness, grief, ego.

Greer says, “My nightstand pile is always somewhat aspirational—some major works that I pretend I’m going to conquer—but mostly it’s friends’ new works, books I’ve never heard of that a friend handed to me, and old favorites to reread. Night time reading is to enter a dreamland before the dreamland—or else to fill the sleepless hours. One never knows what will do the trick!”

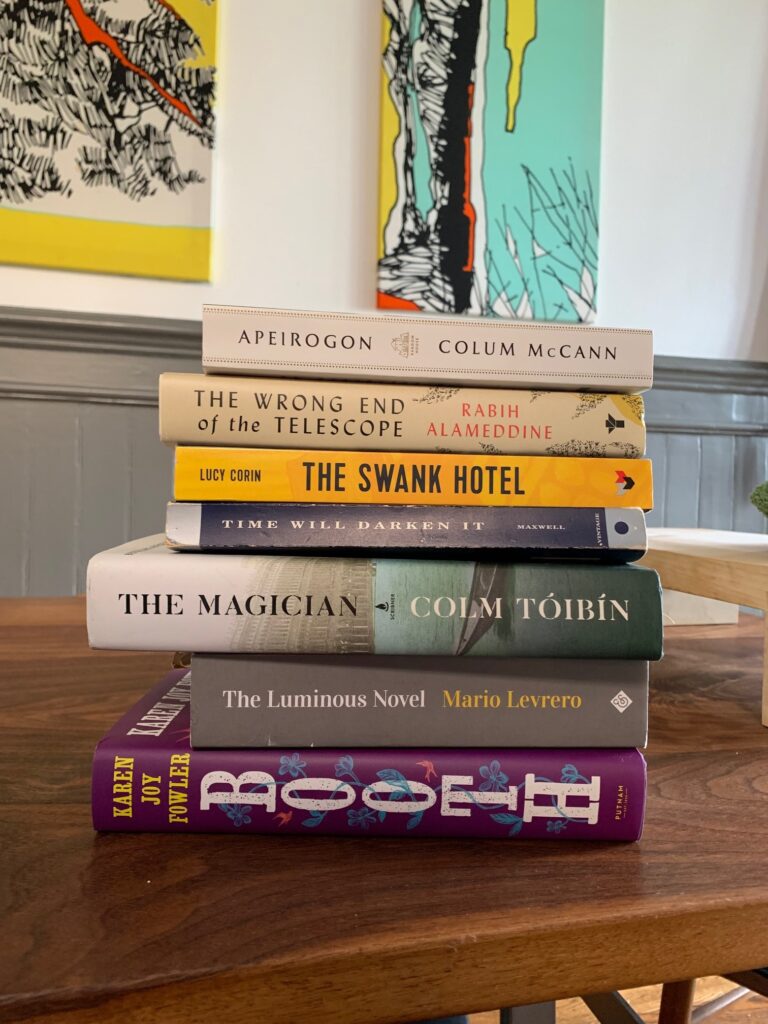

Colum McCann, Apeirogon

This novel from 2020 considers the impacts of the deaths of two girls in Jerusalem: a Jewish 13-year-old by Palestinian bomb, and a 10-year-old Palestinian by an Israeli sniper. The former died in 1997, the latter in 2007. The New York Times review states, “An apeirogon is a polygon with an infinite yet countable number of sides. This novel, divided into 1,001 fragmentary chapters — a number alluding to “The Thousand and One Arabian Nights” — reflects the infinite complications that underlie the girls’ deaths, and the unending grief that follows. Its primary subject is the fraternal relationship between the girls’ fathers.”

Rabih Alameddine, The Wrong End of the Telescope

The winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction follows the Lebanese doctor Mina as she arrives at Moria refugee camp in Greece. This is, to some degree, inspired by Alameddine’s experience at this refugee camp after much time interviewing refugees in his home country of Lebanon through the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees. In an interview with David Naimon, Alameddine explains, “In Lesbos, there was also this whole thing of the volunteers and who they were, and why they were there…I was there because I wanted the world to see me as someone who is caring, not about the refugees.” This impulse of himself and others to “go on a vacation and help people,” is something Alameddine investigates through Mina and her work with depth and complication.

Lucy Corin, The Swank Hotel

Corin’s novel largely focuses on the relationship between the protagonist Em and her sister Ad. Ad’s mental illness has marked the family, and she frequently disappears. She’s eventually found, unconscious, and in a coma. The Publishers Weekly review states, “Marked by Corin’s limber voice, this brims with genuine depth and humor, particularly when unacquainted characters discover previously-unseen commonalities, as is the case with Em and her gruff coworker, Frank, a former manager whose own relationship with his lover Jack is marked by instability. Delightfully askew, Corin’s work offers a memorable exploration of how a loved one’s mental illness can impact an individual’s outlook.”

William Maxwell, Time Will Darken It

This novel is set in 1912 Illinois, and was by the New Yorker editor known for attending to the writings of Frank O’Hara, and John Cheever, I found a review from its year of publication in 1948. In that year The Atlantic describes it as “A distinguished novel,” and sums it up thusly: “Mr. Maxwell’s hero, Austin King, is an attractive, well-meaning young lawyer, who devotes himself to ‘the never-ending effort to do what was right.’… Crisis and tragedy grow out of a visit from distant relatives: Nora Potter, a childish, moon-struck young girl, falls desperately in love with Austin, and he is too compassionate and too weak to cope firmly with the situation.”

Colm Tóibín, The Magician

As with his novel The Master on Henry James, Tóibín here gives us the complicated life of Thomas Mann—one defined by wracking closeted desires alongside his remarkable successes including the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929. Tóibín imagines the inspiration for Mann’s Death in Venice as a boy Mann sees while in Venice in 1911: “The boy crossed the dining room with quiet self-possession. He was blond, with curls that stretched almost to his shoulder. He wore an English sailor suit.”

Mario Levrero (trans. Annie McDermott), The Luminous Novel

The Kirkus review of this meta-novel by the Uruguayan author Mario Levrero describes the book as such: “Our narrator, Levrero himself, is a grumbler of Dostoyevskian proportions, to say nothing of a supremely accomplished procrastinator.” Levrero has earned a Guggenheim, and cannot complete the task he set out in his application: write a novel. The review continues, “Depressed and ill, our narrator finally concludes that the luminous novel of his dreams is really an autobiography, and life is getting in the way of his writing it. Levrero, a photographer, experimental writer, and humorist, clearly revels in the prospect of writing an unclassifiable novel, as this surely is, but even more clearly he delights in not meeting his obligation to Guggenheim.”

Karen Joy Fowler, Booth

This historical novel on John Wilkes Booth has landed a place on more than half a dozen “most anticipated” lists and earned several starred reviews. Neel Mukherjee doesn’t hold back in his praise, either. He writes, “Like Tolstoy before her, and Natalia Ginzburg, Karen Joy Fowler understands that the only way to write about history is as clattery, complex dramas of ordinary people and their families—they become the stuff of history later. Booth is a subtly devastating meditation…Its world—dense, granular, intricate—is created with immense care and precision, and rendered in prose of limpid, lyrical beauty. This is her finest, most beautiful novel to date.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.