The Annotated Nightstand: What An Yu is Reading Now and Next

Julie Otsuka, Rachel Yoder, Elizabeth McCracken and More

Though Song Yan wants a child, and her husband bats away her requests to try again and again. One response is as if she is asking him to complete a chore, when he tells her, “I don’t have time right now. It’s raining. The traffic is probably horrible.” Song Yan’s consistent interactions with children are as their piano teacher, after giving up her own pursuit of the instrument. Then her mother-in-law comes to their Beijing apartment from the far-flung Yannan province, quickly followed by mystery parcels of mushrooms from the same region.

So unlocks the increasingly surreal and compelling story An Yu has created of a woman who feels increasingly trapped in her life’s story. Song Yan’s connection with music is no longer what she had hoped. Her husband is secretive and remote, and her sense of purpose in connection with a child isn’t possible without him. “Solitude is tolerable, even enjoyable at times,” she says. “But when you realise you’ve given your life to someone, yet you know nothing but his name? That kind of solitude is loneliness. That’s what kills you.”

Yet Song Yan’s life is persistently injected with the mystery of the mushroom parcels, a reminder of something outside the life that largely is defined by its limits. Alexander Kleeman in his review of Ghost Music in the New York Times writes, “Unable to fully accept or reject their circumstances, unable to let go of old attachments or hold tightly enough to them to remain grounded, the living characters who populate the novel seem more adrift than the ghosts… What comes to feel most mournful about Yu’s human characters is their inability to express their desires, to translate their intense longing into a simple request.”

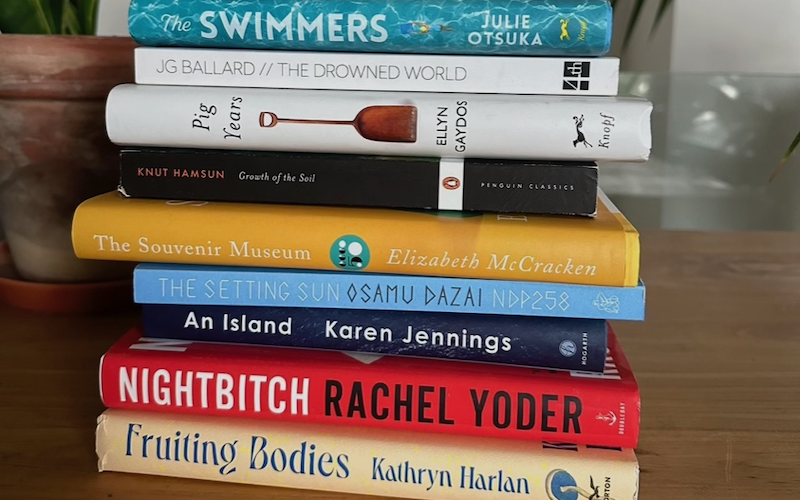

An Yu explains, “My current TBR pile, it seems, has nothing to do with work. I’ve been trying to give myself some distance from the novel I am working on, so everything here is consumed as a way to rewind and rekindle my imagination. Perhaps that is why most of these stories are closely linked with the earth and water, with nature and cycles, with solitude and suffering—subjects that always succeed in bringing me back to myself.”

Julie Otsuka, The Swimmers

As a habitual swimmer, this novel appeals to the reality of the experience at the pool and its impact on the day-to-day. There are people you know, see almost every day, but also know almost nothing about them—even if you have seen them naked more times than you can count. The ritual of doing laps is taken away from the regulars, including the book’s protagonist Alice, who is subsequently forced to contend with her dementia (otherwise held at bay with her swimming and pool community). Her experiences earlier in life, including her memories of incarceration during WWII in the US as a Japanese American, start to bleed into her contemporary moment.

J.G. Ballard, The Drowned World

Ballard’s 1962 novel is considered foundational for “climate fiction,” as it shows a world reduced to a post-apocalyptic state by extensive solar radiation. Ballard was incredibly accomplished, having won a Booker, received the Golden PEN Award. What is compelling to me, however, is that apparently Ballard has an enormous impact on the cyberpunk movement. Beyond this, he has influenced a remarkable amount of musicians, with several writing songs that reference him and his work. These include but are not limited to Madonna (“Drowned World”), The Buggles (“Video Killed the Radio Star”), Joy Division (“Atrocity Exhibition”).

Ellyn Gaydos, Pig Years

The New Yorker review-in-brief writes of Pig Years, “In this evocative memoir of working as a seasonal farmhand in upstate New York and Vermont, Gaydos offers what, at first, reads like a straightforward catalogue of farm life: how pigs are raised and slaughtered; how radishes are harvested; where farmhands sleep. But the tranquil simplicity belies a deeper purpose. The farms where Gaydos works are independent, their output extremely vulnerable to the whims of nature; she has seen crops fail and ‘worms rot a flock of sheep from the hooves up.’ And people are scarcely less vulnerable than livestock: a farmhand contracts Lyme disease; Gaydos has a miscarriage. Our dominion over nature, it becomes clear, is incomplete. The reason Gaydos likes farming, she writes, is that ‘one simply must accept the outcome.’”

Knut Hamsun (trans. Sverre Lyngstad), Growth of the Soil

Growth of the Soil earned Hamsun the Nobel Prize in 1920. I appreciated reading a New York Times review of a 1923 biography of Hamsun by Hanna Astrup Larson. “Notwithstanding his popularity achieved by ‘Growth of the Soil,’ the American public knows little of Knut Hamsun as a writer and almost nothing of him as a man,” writes the reviewer. Describing the author’s childhood in Norway, they write, “During long Summer [sic] days he herded cattle, and being much alone in the fields and woods, he learned to know nature and to love it. What schooling he had ended in his confirmation… After that, he was apprenticed to a cobbler.

Even at that time, he had made up his mind to be a poet.” After leaving cobbling for an array of positions and efforts, including coal heaving, teaching, sheriff clerk, college student, émigré, Chicago streetcar conductor, North Dakota fieldhand, he finally returned to Norway to focus on writing.

Elizabeth McCracken, The Souvenir Museum

The titular story from this beloved collection was published in Harpers. The story begins: “Perhaps she should have known that she would find her lost love—her Viking husband, gone these many years—in Sydesgaard, on the island of Funen, in the village of his people. Asleep in the hut of the medicine woman, comforted by the medicine woman, loved by the medicine woman, who was (it turned out) a podiatrist from Aarhus named Flora. The village itself was an educational site and a vacation spot where, if you wanted, you could wear a costume and spin wool for fun. As for Aksel—was he Joanna’s common-law ex-husband, or ex-common-law husband? Eleven years ago they had broken up after living together for ten. ‘Broken up’—one summer Aksel left for Denmark, and she never heard from him again.”

Osamu Dazai (trans. Donald Keene), The Setting Sun

I recommend reading Dazai’s Wikipedia page, if only for the wild ride that it is (disowned by his family for running away with a geisha, arrests for involvement with the Japanese Communist Party, wife cheating on him with his best friend). The American bombing of Tokyo burned his home down—twice. While they often rejected Dazai’s writing, the draconian censors accepted more of his work than almost any other writer of the time. While he died when she was only one, Dazai’s daughter Satoko Tsushima (aka Yuko Tsushima) became a remarkably successful writer in her own right, with the New York Times calling her “one of the most important Japanese writers of her generation” in 1988.

Karen Jennings, An Island

In an interview with C. A. Davids at Electric Literature, Jennings states, “I must admit to feeling some frustration with the way in which this still happens throughout Africa. We wait for the UK or America to tell us which of our own people are worth reading. In my experience, there is a certain view of Africa and of the stories that can be told and sold that dominates amongst overseas publishers. If those same people are telling us who to read, what to read, what to write, who we are, then we lose authenticity. Does that mean that recognition from outside is not useful, that it should be eschewed? No, of course not. As you said, it is practical. It offers a valuable step towards getting people from outside of Africa to pay more attention to what is coming from within Africa. The hope is that the more Africa is being seen, the more open publishers and readers will be to reading its authors.” You can read an excerpt of the Booker long-listed novel on our own LitHub.

Rachel Yoder, Nightbitch

A friend recently recommended this novel to me and so I’ve had my eye on it. Yoder wrote the book largely in response to the reasonable frustration at what motherhood and the shape it ended up taking in her own life. In an NPR interview she states, “when I found myself in this position—a stay-at-home mom, my husband on the road every week—I thought to myself, how did I arrive here?” The protagonist in Nightbitch starts to have a ravenous desire for raw meat. Then a tail emerges. She plays fetch with her son. In a sense, the ways in which motherhood is feral, and yet is damnably confined by society, is what this book circles around and around in enticing ways.

Kathryn Harlan, Fruiting Bodies

I love the echoes between An Yu’s novel and Harlan’s debut collection (mushrooms play a starring role). And this is also true of both author’s texts, with mushrooms, mysteriously, appearing where they seem they shouldn’t, or wouldn’t. The Publishers Weekly review states, “In Harlan’s enticing debut collection, primarily queer, female characters encounter surreal and fantastical situations. In the title story, the protagonist’s lover becomes mysteriously mycological, sprouting various types of mushrooms the partners can cook and enjoy—or use to poison an unwitting, uninvited guest.”