The Annotated Nightstand: What Amy Silverberg Is Reading Now, and Next

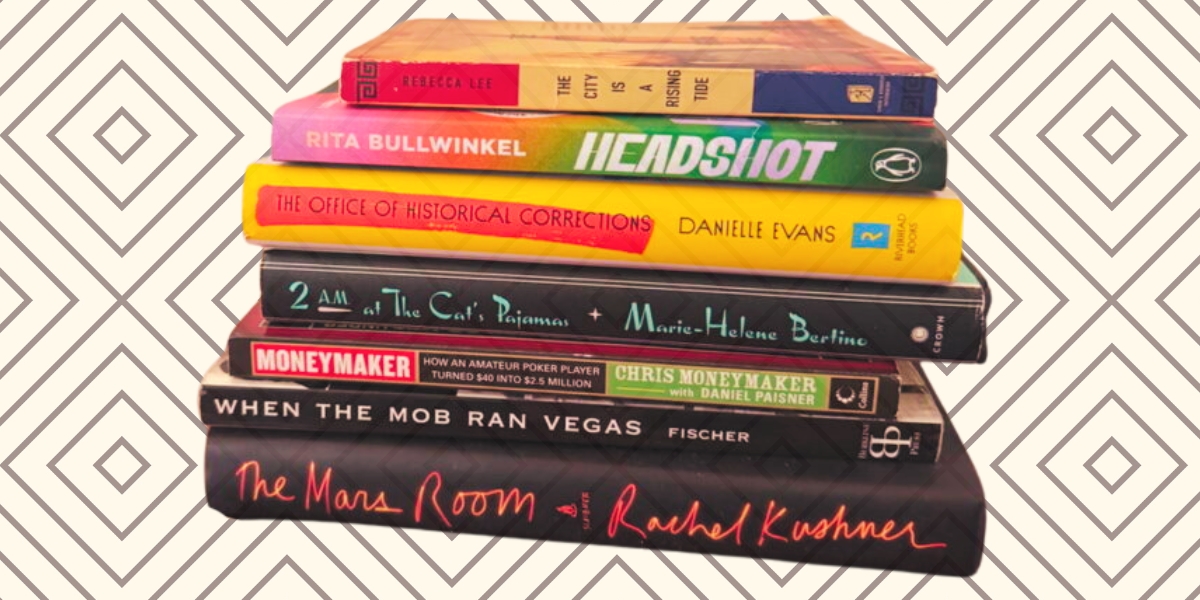

Featuring Rita Bullwinkel, Rebecca Lee, Marie-Helene Bertino, and Others

Allison, a writer in her late twenties, fled small-town Nevada for Los Angeles where “so many jobs were required to cobble a life together,” she explains in Amy Silverberg’s First Time, Long Time. “What would my life look like to other people? A disheveled pile, a tattered quilt.” (Relatable!)

Allison teaches writing in community college, runs book clubs for wealthy women who often do little more than peruse the blurbs, and avoids actually writing the fiction she intends to write. Then she randomly meets a Howard Stern-type radio personality she and her father listened to as she grew up and gives him her number.

The defining features of Allison’s life are given in a slow drip. “In every family you were lucky if you felt understood by even one other person,” she says. That person was her brother—who died two years ago. The overlaps between her own family and that of her soon-boyfriend Reid and his adult daughter make her wary, but also drawn in.

At moments Reid is a stand-in father for the real one Allison holds at arm’s length. Reid’s daughter Emma is pursuing comedy—like Allison’s brother did. Emma is also hot, flirty, and has a smaller age gap from Allison. (When Allison tells Emma “I’m older.” Emma’s response: “Not by that much.”)

While this might sound stressful or drama-heavy premise, Silverberg also accomplishes a kind of magic by threading humor throughout. “Would I have been attracted to him if he was just any man my dad’s age, alone at a bar?” Allison asks herself at one point. “Bald?!”

First Time, Long Time interrogates notions of persona and reinvention, which of course are the other defining features of Los Angeles—the big-time version of “getting out” of small-town life. The scenes often slam shut in a way that makes you sit up (in a good way).

Silverberg says of her to-read pile:

I’m currently working on projects about poker and historic Las Vegas, so I’m reading both toward subject matter and style. I’m not a writer that normally researches, so it’s new for me (and I’m doing a very minimal amount). The other books in the pile are just books that I admire stylistically and structurally—I’m always trying to read books that might inspire me to stretch myself, and to try something new. Most of all, I want to read sentences I admire, that I wish I’d written myself.

*

Rebecca Lee, The City Is a Rising Tide

Kirkus says of Lee’s first novel:

Narrator Justine Laxness is herself a citizen of two cultures: China, where she spent much of her childhood as the daughter of wealthy missionary parents, and New York City, where she works (in 1993) for the nonprofit Aquinas Foundation, dedicated “to promot[ing] the intersection of Eastern and Western medicine” throughout the world. Aquinas’s plans are threatened by a Chinese government plan to build a ‘dam extension’ on the Yangtze River, which would flood land reserved for a state-of-the-art “healing center.”

Rita Bullwinkel, Headshot

The novel was a finalist for the Booker Prize. The Booker Prizes interviewed Bullwinkel, in which she says,

I wrote this book l because I wanted to remember how I felt when I was a young woman and obsessively competed in every sport I could find….My hope is that boxers, and lovers of boxing, will find authenticity in this book, but that also anyone who has ever been gripped by an obsessive drive to accomplish something, and to be seen at a time when they felt otherwise invisible, will find themselves in these pages.

Danielle Evans, The Office of Historical Corrections: A Novella and Stories

Joseph Peschel reviewed Evans’ collection for the Brooklyn Rail, where he writes,

In Evans’s novella, a former history professor, Dr. Cassandra “Cassie” Jacobs, works as a field agent for the Institute for Public History (IPH) in Washington, D.C. The department was created by the demands of an ambitious freshman congresswoman who wanted to install public historians throughout the country to correct the “contemporary crisis of truth.”

That crisis seems especially relevant today when we have a president who is so economical with the truth that his statements will take years to rectify. Cassie’s job, though, is to ‘protect the historical record’ and make corrections without picking fights and without correcting people’s opinions of current news.

Marie-Helene Bertino, 2 A.M. at the Cat’s Pajamas

At NPR, Colin Swyer describes the protagonist of 2 A.M. Madeleine as

a chain-smoking nine-year-old with the mouth of a sailor and the voice of a torch singer. Her mother died recently, her father can’t get out of bed and her apartment’s so infested with cockroaches, she goes from room to room announcing herself just to get them to scatter. But she also dreams of singing jazz standards onstage, and she practices relentlessly to be ready when it happens.

Chris Moneymaker, Daniel Paisner, Moneymaker: How an Amateur Poker Player Turned $40 into $2.5 Million

A.J. Jacobs writes of Moneymaker at the New York Times, “Put it this way: After reading Moneymaker: How an Amateur Poker Player Turned $40 Into $2.5 Million at the World Series of Poker, I was half convinced that I could wangle my way to the final table of the World Series at Binion’s Horseshoe Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. And I play poker at a third-grade level.”

He adds, “This book is two hundred and forty pages of false hope.”

Steve Fischer, When the Mob Ran Vegas: Stories of Money, Mayhem and Murder

The jacket copy for this book reads:

What is so captivating about Vegas? Is it how the skim worked and how millions of dollars vanished uncounted? Ever hear about the bad guys that rigged the gin rummy games at the Friars Club and took a bunch of famous people to the cleaners? Steve Fischer, an avid researcher and collector, bring us Vegas like you’ve never seen, tales you’ve never heard—until now.

Rachel Kushner, The Mars Room

Juan Haines, an incarcerated man who reviews book for the San Quentin News, writes,

The Mars Room is centered on everything bad that happens to a person while locked up—things beyond even being stripped away from friends and family. It addressed accepting responsibility, being accountable for the harm you’ve committed against innocent folks, and sitting in the fire of regret and remorse.

Being in the latter myself—the regretful and remorseful kind—I wasn’t very excited to pick up a novel about the worst and least bearable parts of prison life. Nevertheless, I kept turning the pages.

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.