The Annotated Nightstand: What Tammy Nguyễn is Reading Now and Next

A Series by Diana Arterian

When I first read Tammy Nguyen’s chapbook Phong Nha, the Making of an American Smile, I was immediately drawn to her capacity to weave a tight braid for me to trace. She leapt from being a girl born without two adult front teeth (and, after much time, effort, and money, to eventual “correction”), the cave formations of Phong Nha in Vietnam, the human-made “Forest City” island in Malaysia, articles from Vietnam’s 1992 Constitution regarding land and land use.

Through these topics, Nguyen is able to adeptly scrutinize concerns of societal expectations, land, family, and American ideals. So, I was thrilled to see the chapbook’s publisher Ugly Duckling Presse was releasing a full-length work by Nguyen entitled O—an expansion of her chapbook. “O-O-O-O-O-O-O-O” recurs throughout—what people call from zip lines, a call for attention, the wind, crooners, a dentist’s request as she opens her mouth. O, like the chapbook, is an accretive work that comes together in activating ways, creates links you never would have made yourself.

Nguyen’s uncle, who immigrated to the U.S. and changed his name to the Americanized “David Van,” is a primary character in O. He wholly embraces Americanist ideals: its exceptionalism, lauding economic survival of the fittest—the canniest with their exploits or exploitations. “Teeth are everything,” He explains to her parents when Nguyen is a child. “The Americans take you seriously when you have a nice set of teeth. It doesn’t matter how smart you are—if you have a good face with nice, straight white teeth, people will take you seriously in this country. You’d better take her to see the orthodontist.”

Throughout, Nguyen approaches the multitudinous ways in which human perception of value shapes our actions, our mouths, the land, and beyond. She is able to maintain a tone of playfulness throughout, while exploring the arguably dark impulse to have or create something human-made, rather than what emerges “naturally” (false implanted teeth, a wealthy island city, an American identity, a nation).

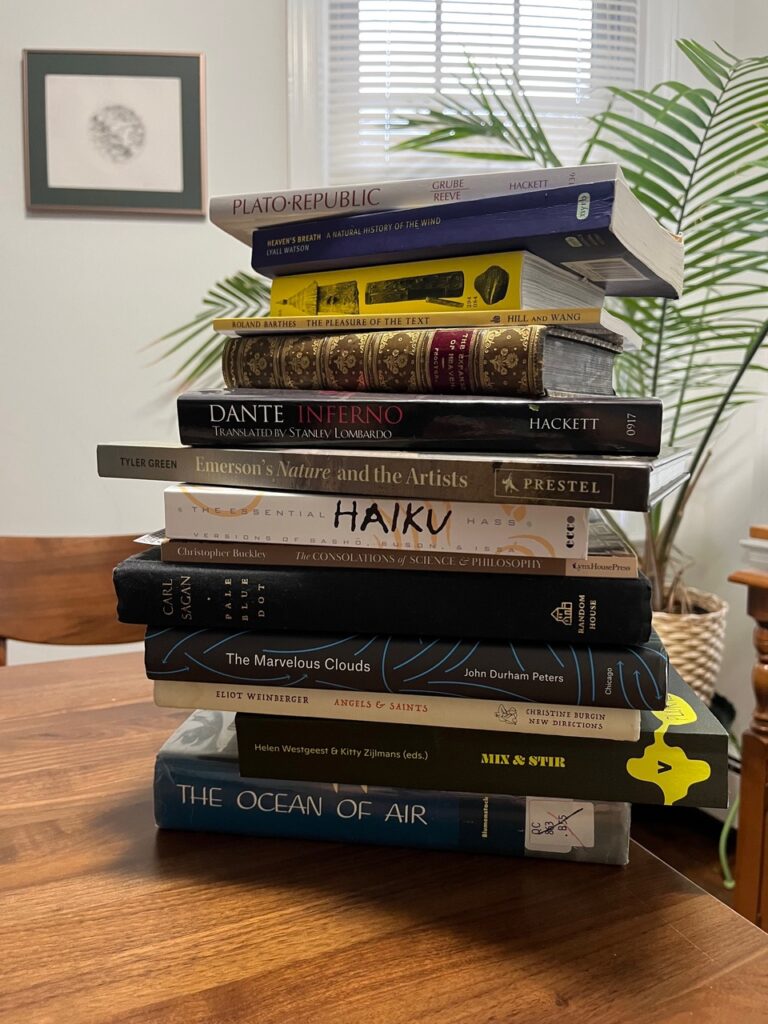

Nguyen tells us about her to-read pile: “My pile of books come to me from all over the place—recommendations from friends, cool Instagram accounts, syllabi from courses that I wish I could take, and more. Right now, I’m interested in Nature, language, religion and how that all comprises our sense of truth. I’m exploring how I can collapse the subjects of the environment, outer space, Christianity, and ethics. I read these books deeply and casually, perusing them all at once and sometimes spending more time on one than the other.”

Plato, Republic (trans. G.M.A. Grube & C.D.C. Reeve)

This dialog often sticks in the minds of many poets. “[T]here is an old quarrel between philosophy and poetry,” Plato explains. And this quarrel is dire enough for Plato to argue that some of those who loom large (Homer, Aeschylus) should be banished from of the idyllic republic for all the falsities they tout. I’m very curious about this “revised” translation by Reeve (something I have never seen before), which the publisher argues “follows and furthers Grube’s noted success in combining fidelity to Plato’s text with natural readability, while reflecting the fruits of new scholarship and insights into Plato’s thought.”

Lyall Watson, Heaven’s Breath: A Natural History of the Wind

The New Yorker review for the Heaven’s Breath states that it begins with the simplest of definitions—“‘Wind is defined as air in motion’—before spinning out into a dizzying series of explanations, factoids, mini-histories, and cosmic contemplations. Within a few pages, an explanation of wind chill segues into a description of shivering, then moves on to a citation of Darwin’s Beagle voyage, the unit of the Clo… the fashions of ancient Crete, rooftop ventilation techniques in Pakistan, and the formation of heat islands in cities. There is a surprisingly useful taxonomy of clouds and a discussion of whether viruses are dropped into the earth’s atmosphere by comet dust.”

Aladin Borioli, Hives (with an essay by Ellen Lapper and Aladin Borioli)

In an interview with It’s Nice That, Borioli explained why there is a dearth of knowledge regarding beehives’ history. “Firstly, ‘hives have always been built with quite fragile material—cow dung, straw, clay and wood—largely curtailing their longevity,’ Aladin explains. Secondly, there isn’t much interest in the subject of beehives, by way of research and academia.” Yet Borioli dives deep into this book: “Spanning the baffling timeline of Egypt, 2400 B.C.E. to 1852 C.E.… Hives excavates centuries worth of extraordinary architectural beehive diversity.”

Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text (trans. Robert Miller)

I think of this quote from this slim-but-mighty Barthes book often: “Is not the most erotic portion of a body where the garment gapes?” While Barthes gave more thorough definitions of readerly vs writerly text in S/Z, this tantalizingly open cloth is akin to the writerly text—that which acts as an invitation to the reader. The reader’s active participation with the work is required for it to make meaning, and provide them, ultimately, with “jouissance.”

Richard A. Proctor, The Expanse of Heaven: A Series of Essays on the Wonders of the Firmament

I have not come across this book before, written by the 19th Century English astronomer who apparently was the first to create maps of Mars—and even has a crater bearing his name for the achievement. Its tone is of its time, and seems, now, wildly outside of how a scientist might write. He begins: “On a time I dreamed, and my dream was on this wise. In a vast black expanse there appeared a glowing orb…It shone with a mighty light, whiter than the driven snow, and more intense than the light from the heart of the fiercest furnace.”

Dante, Inferno (trans. Stanley Lombardo)

I struggle to give some novel insight about Dante’s Inferno, save, perhaps, for the small fact that William Blake made a series of illustrations to the poem. While this may not seem so surprising—Blake, after all, illustrated his own all-too-famous Songs of Innocence & Experience—his illustrations are jaw-dropping in their wildness. The surreal ways he depicted a variety of scenes are surreal, colorful, full of motion. You can even get a phone case of “The Circle of the Lustful,” if you desire. Or just read more about the pieces from the Tate Modern here.

Tyler Green, Emerson’s Nature and the Artists: Idea as Landscape, Landscape as Idea

As the jacket copy for this book states, “Illustrated by classic American paintings and photographs, and accompanied with a prescient new appraisal, this stunning publication on Emerson’s seminal 1836 essay is at once a meditation on the ways artists influence each other and a timely cri de coeur to cherish and preserve America’s landscape.”

Robert Hass (editor and translator), The Essential Haiku: Versions of Bashō, Buson, and Issa

I was lucky enough to see Hass read from this collection when it first came out. I think of one Buson haiku in Hass’ translation: “The two plum trees— / I love their blooming! / One early one later.” Hass’ close-reading of the poem was that it was one of accepting difference rather than uniformity. No matter that one blooms early, the other later—both create a feeling of love for Buson.

Christopher Buckley, The Consolations of Science & Philosophy

Naomi Shihab Nye says of the poetry collection The Consolations of Science & Philosophy, “Buckley’s gift for wide-ranging thinking meshes so gracefully with lovingly tender details, he feels like a companion voice for all time… and we are caught up in a spell of unfolding images, an arc of compelling music, and his passionate care for what we can and cannot change.”

Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot

The title of this book is based on the image Voyager 1 took of Earth just as it was at the edge of the solar system in 1990, heading farther away from us. You have to squint to see it. Sagan commands, “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.” Considering Nguyen’s work and what I love about it, at this point I’m excited—I can see how she’s digging in deep regarding space, air, wind, the celestial. I can’t wait to see where she goes with it in her next book.

John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media

In an interview in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Peters answers the question that is essentially “why clouds?” with the following: “clouds raise very fundamental questions of where significance lies. Clouds are often thought to be blank and meaningless, the playthings of whimsy. Hardly. Few things are so packed with meaning. Once you start looking at clouds, you see them everywhere in art, literature, religion, and popular culture, and of course in the sky. The question of what clouds mean is a deep one; reading clouds is the paradigm case of how to interpret nature and how not to. Clouds tell us about the weather and the future, and reading the sky is a basic human task.”

Eliot Weinberger, Angels & Saints

The New York Times pins down the concerns of this book with a few lines of pithy description, stating, “What do we believe about angels? Weinberger distills the cultural record in all its contradictions: They are immaterial, yet in the Bible they eat and drink; they are purely good, yet in the Gospels they sometimes engage in deception.”

Helen Westgeest & Kitty Zijlmans (eds.), Mix & Stir: New Outlooks on Contemporary Art from Global Perspectives

Visual artists and scholars contribute to this collection, the cover of which makes it hard to look away. (Hives, too, had this visual impact.) This anthology is from the publisher Valiz’s “Plural” series, one that “focuses on how the intersections between identity, power, representation and emancipation play out in the arts and in cultural practices. The volumes in this series aim to do justice to the plurality of voices, experiences and perspectives in society and in arts and design.”

David I. Blumenstock, The Ocean of Air

I found a review of this book from a journal entitled The American Biology Teacher from 1961. It states the book “attempts to bring together information about the earth’s atmosphere; its behavior and movements; man’s attempts to observe, predict, and control it; and its influence on the ecology of man.” I love the half-page ad, just below, a for a student microscope: “Ten years from now you’ll be glad you bought Graf-Apso.”

Diana Arterian

Diana Arterian is the author of the recent poetry collection Agrippina the Younger (Northwestern UP, 2025) and editor and co-translator of Smoke Drifts (World Poetry Books, 2025), a collection of Nadia Anjuman's poetry. A Poetry Editor at Noemi Press, Diana has received fellowships from the Banff Centre, Millay Arts, and Yaddo. She writes “The Annotated Nightstand” column at Lit Hub and lives in Los Angeles.