The (Almost) Wildness of Elizabeth Bennet

Devoney Looser on the Perennial Appeal of Jane Austen’s Remarkable Heroine

Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennet is among the most beloved and recognized heroines in literature, with far more than her “pair of fine eyes” and “pretty face” to recommend her. Her lively mind and vigorous physicality also capture the attention and heart of hero Mr. Darcy—and most readers—although the novel makes it clear that she’s found haters in her world, too.

When Elizabeth is described behind her back by a frenemy (Caroline Bingley’s sister) as looking “almost wild,” it’s delivered as a haughty insult. Yet readers are meant to sympathize with the heroine at this moment, not with the woman who’s throwing shade. Elizabeth’s almost-wildness is one of the most fascinating and appealing parts of her character, and it deserves serious unpacking.

The novel’s brilliant first line—“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”—gets so much critical attention that we may inadvertently gloss over the complicated and slow rollout of its central characters. By the end of the novel, that opening line has been both called into question and ratified.

Heroine Elizabeth is famous for her own refusals, but she’s actually first caught in the middle of two acts of petulant male defiance. First, her father, Mr. Bennet, pretends to refuse to meet his new neighbor, the eligible Mr. Bingley. This annoys his wife, who hankers after Bingley (sight unseen) as a future son-in-law. Elizabeth is drawn into her bickering parents’ argument as she decorates a hat.

In the following chapter, the extremely wealthy Mr. Darcy, newcomer and friend to Mr. Bingley, not only refuses to dance with Elizabeth at the ball but also won’t appreciate her attractiveness. She famously overhears Mr. Darcy reject Bingley’s suggestion that he ask her to dance. Darcy insults Elizabeth as “tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.”

Of course, Lizzy (as she’s also familiarly called in the novel) could have stoically kept this nugget to herself or revealed her humiliation to a select few. Instead, she decides to give the story legs. She repeats it “with great spirit among her friends” at the ball—and presumably afterward. We’re told that, after rejection, Lizzy pivots to eavesdropping and gossiping because she “had a lively, playful disposition, which delighted in any thing ridiculous.”

Elizabeth has long been celebrated in literary history and among feminists for the admirable ways she says no.

What’s evident is that Elizabeth shares a disposition with her satirical father. We’re meant to laugh right along with both of them. But if we do so, it’s because we’re temporarily forgetting that listening in on conversations and rumormongering aren’t exactly model behaviors. Elizabeth comes close to crossing a line into impropriety here, which she’ll do again and again over the course of the novel. It all unfolds as she takes up the mantle—first established by her father and then by Mr. Darcy—to become the novel’s most prominent refuser (or mock-refuser) of polite convention.

Elizabeth has long been celebrated in literary history and among feminists for the admirable ways she says no. After rejecting two offers of marriage, from Mr. Collins and Mr. Darcy, she defies Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s admonition to refuse Darcy’s hand. An early dramatization of Pride and Prejudice by the socialist feminist playwright Margaret Macnamara retitles her adaptation Elizabeth Refuses (1926), which highlights this very point. It’s no accident that Elizabeth’s domestic protest speeches were excerpted for standalone amateur performance by the New Woman and women’s suffrage movements. The original novel includes material that’s sympathetic to the aims of the women’s movement.

Those fin de siècle playwrights, activists, and actors were recognizing something important about this remarkable heroine. We don’t judge Elizabeth harshly for going against polite strictures, because she’s often revealing some hypocrisy or injustice. Mr. Bennet usually punches down (as we’d put it today) in criticizing his wife and his “silly and ignorant” daughters. But Lizzy generally punches up, directing her barbs at and refusing the marching orders given by those more powerful than she is. We may also be more likely to give her a pass because we’re measuring her words and actions against those of the novel’s other female characters, especially her flirtatious youngest sister, Lydia.

Mrs. Bennet can’t see which daughter’s behavior presents the greater danger. She criticizes Lizzy, not Lydia, for her wildness. When Lizzy and Mr. Darcy are engaged in very spirited banter at Netherfield, Mrs. Bennet thrusts herself into their conversation, mirroring what we saw Lizzy experience when caught in the middle of her own bickering parents. This time, however, Mrs. Bennet breaks in to complain about her daughter. She says, “Lizzy… remember where you are, and do not run on in the wild manner that you are suffered to do at home.”

Their two consonant names, Lizzy and Lydia, invite comparison and contrast. These are the two most energetic, extroverted, and clever Bennet sisters. Each is the favorite of (and closely resembles) one of her parents, Lizzy her father and Lydia her mother. But Lizzy, with the advantage of five years’ further maturation, has a different relationship to social danger. She marches self-righteously toward it, then stops short of catastrophe; Lydia heedlessly dashes in, sure of herself, never putting on the brakes.

Both Lizzy and Lydia, by following their own desires, jeopardize the economic prospects of their entire family. Lizzy, in rejecting the marriage proposal of her father’s heir, the odious clergyman Mr. Collins, cuts off not just herself but potentially her mother and sisters from future comforts at Longbourn. The devious Mr. Wickham may wow both Lizzy and Lydia with his charisma, but it’s Lydia who impulsively runs off with him, endangering her and her sisters’ marriageability and her family’s continued respectability.

Most fiction of the day made its sexually satiated and so-called “fallen” women pay a terrible price, from illness to shunning to death. These plot details were often accompanied by regret-filled confessions and apologies. But Austen’s Lydia—whose damaged reputation is successfully patched up by a Darcy-driven bargain with Wickham and a hushed, rushed wedding—gets away with it. She ends just as she began, self-assured, with “high animal spirits,” and entirely unrepentant. Lydia succeeds in running wild, but Lizzy may be something just as remarkable and rare. She admirably sustains herself, to the novel’s end, as almost wild.

In Pride and Prejudice, women’s wildness turns on speed. Elizabeth is said to be her father’s favorite because she had “something more of quickness than her sisters.” We might assume this to mean mental agility alone, but her physical quickness often comes into play as well, especially when she decides to set off on foot to visit her sick sister Jane, who is convalescing from a cold at Bingley’s home.

Most fiction of the day made its sexually satiated and so-called “fallen” women pay a terrible price, from illness to shunning to death.

Elizabeth boldly takes a three-mile walk to get there, through ankle-deep mud. Her intrepid walk is described by the narrator in one compact, information-filled sentence: “Elizabeth continued her walk alone, crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles, with impatient activity, and finding herself at last within view of the house, with weary ancles, dirty stockings, and a face glowing with the warmth of exercise.”

Because it’s a signature moment in the novel, it’s unsurprising that these lines have been visually interpreted in so many film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice. What filmmakers can’t seem to agree on is the level of dirt involved. The novel describes it as “six inches deep.” But both the 1957 Italian miniseries and the 1980 BBC television version stay out of the mud entirely, having their Elizabeths arrive at Netherfield in pouring rain, merely bedraggled.

Other adaptations, however, revel in the mire. The 1940 MGM film gets Elizabeth dirty up to her knees, then has her frantically engage in a physical struggle with Netherfield’s boot scraper. Not to be outdone, a 1961 Dutch version has its Elizabeth arrive in mud up to her waist, then shamelessly pans her body in a close-up, from ankles to bosom.

In more recent versions, joy is emphasized over shame. The 1967 BBC version has its insouciant Elizabeth hop a fence stile, discover her muddied hem, then shrug to herself and move on. This scene must have inspired the one in the iconic six-hour 1995 BBC series, which devotes a full minute to Elizabeth’s muddy walk. Here, too, she hops over the fence stile and into the mud, then responds with a happy, self-satisfied shrug.

By comparison, Joe Wright’s 2005 film version went for the pristine approach, leaving Elizabeth’s dirt and delight entirely out of direct view and up to the viewer’s imagination. There’s only a flash of her long walk, shot from a great distance. The camera captures Mr. Darcy’s viewpoint of her on arrival, apparently noticing her eyes brightened by exercise, not her dirty clothes.

The viewer, not having seen her muddied, learns about the dirt later from the film’s Caroline Bingley, who calls Elizabeth’s soiled look “positively medieval”—a line not found in the original novel that suggests Elizabeth is a throwback to dark ages, rather than refreshingly modern. Of course, we aren’t supposed to believe it. Throughout Joe Wright’s film, Darcy’s point of view is emphasized, with the consequence that Elizabeth’s wild actions are often visually muted.

In Austen’s original, however, the point isn’t just to consider the heroine’s and hero’s attitudes toward dirt, from Elizabeth’s nonchalance to Darcy’s attraction. It’s all of this plus the widely differing reactions from everyone else at Netherfield. Jealous Caroline Bingley and her judgmental sister, Mrs. Louisa Hurst, repeatedly drag the reader back into Elizabeth’s mud. In criticizing Elizabeth once she’s out of the room, they take on her earlier gossiping role, with a significant difference. Nothing here is at their own expense. Their point is to take Elizabeth down a peg further as they attempt to ratify their own greater refinement.

It doesn’t work. Miss Bingley can’t get either Mr. Darcy or her brother, Charles, to agree that “to walk three miles, or four miles, or five miles, or whatever it is, above her ancles in dirt, and alone, quite alone” shows “an abominable sort of conceited independence, a most country-town indifference to decorum” in Elizabeth. The men claim they didn’t even notice her dirty petticoat. Later, circling back to the matter, Mrs. Hurst gets in the most cutting, significant line. Elizabeth, she says, “has nothing, in short, to recommend her, but being an excellent walker. I shall never forget her appearance this morning. She really looked almost wild.”

It’s a stunning line that doesn’t get its due, in literary criticism or in most adaptations. As Colin Carman (one of the rare critics who attends to it closely) puts it, “The relationship between wildness and dirt is easy to overlook.” He examines the links among femininity, propriety, gossip, dirt, pornography, politics, nature, and the environment in Austen’s fiction. Another scholar, Kathy Justice Gentile, has also dug deep into the subject of dirt in Austen’s major fiction. More might be said here, however, about women’s wildness, kicking up dirt, and quickness. Mrs. Hurst’s problem with Elizabeth goes beyond dirty laundry; it’s a disgust, too, with female vigor.

Mrs. Hurst’s phrase for Elizabeth, “almost wild,” was quite common in fiction of Austen’s day. It may be found in the pages of more than fifty novels before 1813. It was a set phrase most frequently used to describe a character who becomes “almost wild” with some extreme emotion, including apprehension, delight, exuberance, fright, grief, horror, impatience, jealousy, passion, rage, and terror. But by far the most common thing to be “almost wild” with in the period’s novels was joy. Very rarely is the phrase used to describe a character’s physical appearance or activity, as is the case with Austen’s Elizabeth.

Cataloging these uses of this phrase must widen our sense of the stark differences expressed by Pride and Prejudice’s other characters about Elizabeth’s almost-wildness. The Bingley-Hurst sisters align the heroine’s almost-wildness with fright and horror, describing her as “scampering,” “untidy,” and “blowzy.” They treat her as a dirty intruder, signaling their own desperate jealousy and trying to mark out their spotless superiority. Mrs. Hurst’s invoking of the phrase “almost wild” is meant to cast Elizabeth out of their social circle.

The phrase “almost wild” applied in this way to Elizabeth signals delight, particularly thanks to her eyes “brightened by the exercise” and looking “remarkably well.”

However, for Darcy and Bingley, as well as for the heroine herself, Elizabeth’s arrival at Netherfield is a moment of happy inclusion. The phrase “almost wild” applied in this way to Elizabeth signals delight, particularly thanks to her eyes “brightened by the exercise” and looking “remarkably well.” Readers familiar with the positive and negative uses of the phrase “almost wild” in the era’s novels were being nudged to revise Mrs. Hurst’s insult of Elizabeth’s energy and action into comic, romantic joy.

There’s a further layer of meaning here, too. After Caroline Bingley impugns Elizabeth as a woman of “no conversation, no style, no taste, no beauty,” Mrs. Hurst agrees and continues the tag-team rant. Yet Mrs. Hurst gives Elizabeth one backhanded compliment. She calls her an “excellent walker.” This wasn’t unheard of in novels then. Frances Burney’s Cecilia (1782) has another character praise its heroine, Miss Cecilia Beverley, as an excellent walker. William Godwin’s novel Fleetwood (1805) also lauds a married woman as an excellent walker.

But the most interesting use of the phrase for our purposes appears in Ann Hamilton’s The Irishwoman in London (1810), in which a young newlywed, Ellen O’Gorman, is in the process of trying to leave her abusive husband. She describes herself as an “excellent walker,” capable of going three miles on foot in order to begin her escape from him. The distance coincidentally matches the length of Elizabeth’s walk, but there are other similarities, too. Ellen O’Gorman describes how eventually her “spirit rose against” her cruel husband, a line echoed in Elizabeth’s more playful claim that her “courage always rises with every attempt to intimidate me.” Ellen O’Gorman also tells readers that she “was always fond of the ludicrous,” a line echoed in Elizabeth’s disposition of delighting in the ridiculous.

Austen may or may not have read Hamilton’s novel. Certainly The Irishwoman in London wasn’t a critical or commercial success, although it found its way into prominent circulating libraries. The greater point to be made is that both authors were working with a new iteration of an admirably wild, active, and independent heroine. In both Pride and Prejudice and The Irishwoman in London, these unusual and excellent walkers take matters into their own hands—and feet.

That literary context adds credence to why “almost wild” backfires as an insult and is reimagined (by the author and for the reader) as Mrs. Hurst’s inadvertent compliment. That Pride and Prejudice is able to pull off Elizabeth’s almost-wildness as a delightfully positive quality is a fictional feat, but it’s also a signature aspect of Austen’s method. Even in the early years after its publication, the novel’s feat didn’t go unrecognized.

One 1833 editor praises the “combined boldness and modesty” of Austen’s fiction. He applauds Austen as an author who “struck into a path of her own,” as she “freed herself” from the influence of previous masters of the fiction-writing craft. It’s a compelling and early description of her genius that also succinctly captures the qualities of her striking heroines.

We know Austen, who once jokingly described Pride and Prejudice as “too light, bright, and sparkling,” had strong feelings about Elizabeth. She wrote in a private letter, in lines that read as both a declarative boast and a nagging worry, “I must confess that I think her as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print, & how I shall be able to tolerate those who do not like her, at least, I do not know.” The use of the words “delightful” and “tolerate” here are telling. They’re similar to Darcy’s first insult to Elizabeth’s looks—calling her tolerable—as well as to the nearby line about Elizabeth’s disposition delighting in the ridiculous.

With these lines, Austen seems to express a worry (or a mock-worry) that she might lose her cool with ungenerous readers, not because of their questionable tastes in what makes for a delightful fictional creature, but because of an unshakeable confidence in her own literary creation. “As ever appeared in print” is an immodest claim in the extreme, however comic. It is prideful, impertinent, and may be accused of showing an abominably conceited independence, while also being perfectly true, as literary history would ratify.

In her letter, Austen also nearly reenacts in these lines the scene in which Elizabeth is insulted at the ball. After Austen imagines she’s overheard her creature-heroine disliked, she considers responding in some wild way. Her quasi-threat “I do not know” leaves it up to the imagination. Perhaps, like Elizabeth in the face of Darcy’s insult, Austen would also be prompted to spread spirited gossip about her heroine’s doubters and haters.

As we know now, however, Austen would also take revenge on any ungenerous readers of Elizabeth Bennet by creating more and different heroines in her future novels. If Marianne Dashwood deserves to be understood as Austen’s wildest heroine, and Sense and Sensibility her wildest novel, then Elizabeth and Pride and Prejudice must be celebrated for perfecting the “almost wild” woman in fiction. Austen shows us how others might fear or despise her, then gives us the gift of the means and the courage to delight in her instead.

__________________________________________

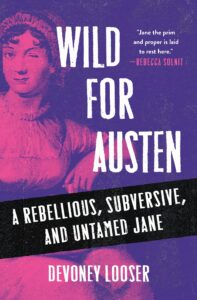

From Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive, and Untamed Jane by Devoney Looser. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Devoney Looser

Devoney Looser, Regents Professor of English at Arizona State University, is author or editor of twelve books, most recently Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive, and Untamed Jane . Her previous books include Sister Novelists (2022) and The Making of Jane Austen (2017). Looser has published essays in The Atlantic, New York Times, Salon, Slate, The TLS, and the Washington Post, and her series of 24 30-minute lectures on Austen is available through The Great Courses and Audible. She is a life member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and has played roller derby under the name Stone Cold Jane Austen.