All is Not Well in the Kingdom

The scripts come one after another. They pile up on the table in his bungalow on the studio lot, the endless gamble of his time and talents, a future that can rest on these choices. He’s learned to spot within ten pages whether it’s a role he can see himself in; some he reads to the end even when he’s determined he either shouldn’t do the picture or can’t do it.

But the reading is the reading. There’s no romance to it, unless you’re Marilyn Monroe, who is constantly photographed reading scripts in various sexy poses, as if the fact of her reading was a surprise. But he’d worked with her in Monkey Business and he knew what she brought to the table; the dumb-blonde act was as much an act as his highborn man. She was constantly recommending books to him that he’d never heard of and never had time to read. But there she was in the magazines, lingering over a script as if this was oxymoronic. He’d said to her, “People are surprised how little education I actually have.” She had said, “People seem surprised I have any at all.” They both had to make up for that lack of schooling, but the difference was he’d chosen to quit the minute he could. The fact that she’d gotten further than he before dropping out didn’t mean she’d wanted to. She read and read; she went to the Actors Studio to study the Method but never seemed to use it in her pictures. Now she’s married to Arthur Miller, and he can’t imagine those high-minded conversations. He’s heard some whispers that Miller’s been writing a big screenplay for her that will change her life.

He, a man with the nom de cinema of Cary Grant, with his truncated education and limited patience, believes he reads a picture the way someone in the audience would watch it: with a need for things to happen. On he reads, dividing the piles on his desk into In and Out piles in which the In pile seems taller every time he walks into the room.

He’s already committed to two new pictures after this year; he’s looking at 1963 at the earliest.

Then after that, he’ll be sixty.

The script at hand is set in Paris, and it’s clear it would be filmed on location. Not so bad, then. In it, he would play a charming man of mysterious means who in the story seems to take on many identities. Right up his alley. And the love interest would be a charming young woman he must help escape a group of murderous men who’d been in cahoots with her recently murdered husband. And there he worries. The character of the girl, Regina, tracks young. And he’d heard through channels that they have Audrey Hepburn in mind. An age difference of twenty-five years. That’s becoming more problematic. She was in Funny Face with Fred Astaire a couple of years ago and

he’d felt a pang of worry about their scripted attraction. Did people really believe it anymore?

On the set again, he sees Scotty smoking a cigarette outside the stage door. Scotty holds out the pack and the Acrobat takes one, then accepts Scotty’s lighter.

“Thought you were quitting these things,” Scotty says. “I’m just getting into character.”

“Your character smokes in a submarine?” “Only off-camera.”

“I didn’t realize you ever got out of character.”

“Well, I did back in fifty-two. Retired for a few months and was beside myself with boredom.” “Funny, most people in this business would rather die with their makeup on.”

“How did you ever find yourself here, Scotty? Working in the pictures.”

“I grew up over in Yorba Linda, back when that was all just orange groves and celery fields. My family had just come from Nova Scotia. I guess I was going to be a farmhand, but then the war started.”

“You fought in the Great War?” “Didn’t everybody?

“I suppose they did, if they were old enough.”

“So when I got back here, the pictures were just really starting up. They were looking for strong boys who could carry heavy things. It sounded harder than farming, but it paid better. In time, they taught me carpentry, then electrical. I picked it all up pretty quickly. There was always demand for workers. Pretty soon, pictures were the biggest thing in this damned town. And that’s the story.”

“I take it you’ve been dealing with people like me for a long time.”

“Oh, I’ve been around people like you forever. You’re not such a bad lot. Once I understand how busted-up needy you all are, I stopped being resentful. Actors are actors, with all the warts you can’t bear people seeing. I’ve had problems with very few stars.”

“Who were the few you did have problems with?”

Besides yourself? The only one I really had friction with was Buster Keaton.” “Why, what did Keaton ever do to you?”

“He was loony, Boss. He’d make us rework the set ten times over until it satisfied him. I was the foreman, so I had to speak up. He’d work us to the bone for nothing, trying to get it right. He was drinking heavy then, though. He knew he was losing it, and it was making him crazy. The doctors tried putting him in a straitjacket, but Houdini had taught him how to escape one, so he kept getting away.”

“Drinking gets the best of them, doesn’t it?”

“Let me tell you, John Gilbert used to breathe fire. But what killed him was that nasal voice of his. When the silent pictures ended, so did he. Dead by his midthirties.”

“You’ve known them all, haven’t you? “No, but I’ve known an awful lot.”

“And will I just be another story for you to tell?” “Nah, Boss, I’ll just be one for you to tell.” “That’s true.”

They both finish their cigarettes, and then Scotty says, “I better get back to it.”

“Scotty, do you ever form an opinion of the pictures you’re working on, watching them being shot?”

“Sometimes you can tell, Boss, but sometimes you can’t. I worked on Public Enemy, and that was something. Everybody knew it. And the cowboy pictures—you almost can’t go wrong. But the ones that weren’t so good, you probably wouldn’t remember.”

“This picture is pretty awful, isn’t it?”

“I’ve been wrong before, Boss, so I’ll keep my opinion to myself. But it’s interesting that you’re asking me.”

“Maybe it’s time for me to get out of the business.”

“Interesting that you’re thinking that, too. But the difference between you and me is, you’re rich enough to have a choice.”

He’s stopped by the bungalow on the studio lot to check his phone messages. James, the publicist from Key West, has left an urgent message. He’s suggested there’s a problem developing. The Acrobat’s lawyer, Stanley, is now holding on the line.

“Stanley, is everything all right?”

“The New York Herald Tribune is going to run Joe Hyams’s series about you, starting in the morning,” Stanley says. “Apparently you went on at some length about this drug use of yours. Sounds as if it wasn’t just a slip of the tongue.”

“First of all, it’s a prescribed treatment. And you need to stop that from happening, Stanley. I never told him he could use that.”

“He’s saying you let Lionel Crane at the London Daily Mirror use the material, and that it’s fair game now.”

“I hardly think so! I have no idea what’s being printed in London. And nobody reads the Daily Mirror anyway! I also don’t want this published in America. That series needs to be stopped.”

“Why did you even talk to reporters about this?” “It was on my mind. So I did.”

“Hitch is very concerned,” Stanley says. “North by Northwest opens in seven weeks.” “Can you get Hyams on the phone for me?”

“I’m not sure that’s a good idea.”

“I insist. I’ll get this squared away.”

“All right, then,” Stanley said, and none too enthused.

But inside of an hour later, the phone rings and it’s Hyams.

“Well, Joe, you need to pull this series I’m just now hearing about.”

“I can’t see that happening, sir. They’ll be running the presses in a few hours. It’s six o’clock back east. Everything is already Linotyped.”

“I told you I’d let you know when you could publish this.”

“I’ve already been scooped by the London paper, so it’s all fair game now. I’m sorry.” “But you simply must pull that series!”

Hyams pauses, then says, “You probably have no idea what it would cost the Herald Tribune to reset the pages on deadline. I’m not going to ask them to do that.”

“I’ll get back to you,” the Acrobat says, hanging up. He redials Stanley and says, “I’m going to deny I ever spoke to him.”

Now it’s Stanley pausing. “I’m not sure if that’s a good idea.”

“Not only did I not give him permission, but Look magazine has now offered a hefty price to me to relate my story. I could choose to talk about it there. If I’m going to discuss the Treatment, why would I give it away to the Herald Tribune for nothing?”

Stanley remains silent.

“Stanley, here’s what to do. Release a statement from me denying I ever spoke to the man.” “Maybe think about that for a little bit,” Stanley said.

“Please, Stanley, I insist. This is the best way to handle things. The last thing I want is this fellow thinking he can speak for me.”

“I doubt he’s going to like that.”

“And why should I be remotely concerned with what a reporter does and doesn’t like?”

“I don’t know what to tell you what to do,” Stanley says. “I don’t know why you ever talked to the press about this at all. Psychiatric treatments. Hallucinatory drugs! It’s probably going to sink the picture. And if it sinks this picture, it will sink the next one, and it’s all going to end up costing you . . .”

*

He paces in his bungalow office at the studio lot, awaiting Joe Hyams’s arrival. The journalist has arranged this after much negotiation, and the moment draws near. The Acrobat does some breathing exercises. This is a focused attempt to get into character, to get into the role called upon right now, which is a man relaxed and mostly amused.

The fallout from the Herald Tribune series has stunned him. After the release of his statement denying having ever spoken to Hyams, the reporter has now sued for defamation. Unheard of, really. In different times, that would have been career suicide—and may still be. The people who cover the movie business have been presumed to not want to alienate the studios, at any cost. One would have presumed Hyams would have quietly receded.

Instead, Hyams has filed a lawsuit for a half million dollars.

“Does he really believe that was the amount of the damage?” the Acrobat says on the phone to Stanley. “It feels like some kind of stunt, and it’s all over the newspapers. Everyone is going to find out if this means the end of the man’s career.”

“Everyone is also going to find out if this will cost you half a million,” Stanley says. “I wish you’d taken my advice.”

“It’s not as if I’m actually being caught in a lie, Stanley. I know I lied, and pretty much everyone else does. That’s beside the point. Or it possibly is the point: It’s the way it works.”

“It’s the way it’s always worked, I agree with that.”

“Louella Parsons has just written about all this. Listen to this: ‘When I was a girl, things were different in the newspaper business.’”

“Yes, the studio arranged that,” Stanley says.

But in the deposition, Stanley says, Hyams has produced the tape recording and a photo taken of them on the deck of the pink submarine, apparently by the studio’s own set photographer. It was all so much bolder than one might expect of a journalist who depends on stars to give him the time of day. Meanwhile, poor James, the studio public relations man, has disappeared from the face of the earth, apparently avoiding a deposition of his own.

“Well, we need to make this go away,” Stanley says, with a curl of gloom on his voice. “Like we always make these things go away.”

__________________________________

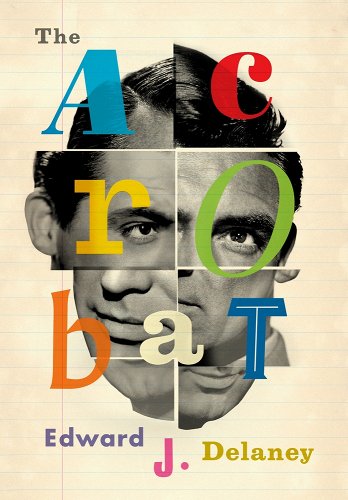

From The Acrobat by Edward J. Delaney. Used with permission of the publisher, Turtle Point Press. Copyright© 2022 by Edward J. Delaney.