The 80-Pound Rule and How Youth Sports Hurt Kids’ Bodies

Virginia Sole-Smith on Diet Culture Starting Young

Before we dig into the very real harm caused by anti-fat bias in youth sports, we need to deal with the most obvious counterargument: that it’s not fatphobia to say that being thinner improves athletic performance—it’s science.

“Weight is an easy target because it’s visible, and we’ve tied it to every performance marker,” says Eva Pila, PhD, an assistant professor in the School of Kinesiology at Western University in Ontario. “I’ve had so many conversations with coaches and high-level trainers where the argument is, ‘Well, this is just basic physics.’”

Consider a sport like rowing, where athletes compete to see who can push a boat through the water the fastest. Pila has worked with coaches who argue that weight management is a critical component of their athletes’ training regimens because the more the boat weighs (and by “the boat,” we mean both the inanimate object and the people sitting inside it), the harder athletes will have to work to push it along. “Nobody asks, ‘Should we build a better boat?’” she notes.

Dana Voelker, PhD, also a kinesiologist and associate professor of sport and exercise psychology at West Virginia University, who has studied weight stigma in figure skating, points to a commonly invoked “80-pound rule,” which dictates that a female figure skater must weigh at least 80 pounds less than the male figure skater who must lift her.

“Why 80 pounds?” she asks. “It’s used as a proclamation of science, but where is that science? And why do we emphasize the female skaters losing weight but focus less on male skaters getting stronger?”

“It’s just physics” also assumes fat athletes can’t bring other skills to a sport beyond their physical presence. But fat people can be strong, fast, flexible, and graceful. And research on the relationship between weight and physical fitness, much like the relationship between weight and health outcomes, is largely correlative and clearest at the extreme ends of the BMI scale, both high and low.

“When you look at everybody in the middle, it’s not so clear,” says Christy Greenleaf, PhD, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. “There are people in bigger bodies that can do all kinds of physical activities at high levels.”

Many have cult followings on social media: The fat activist and writer Ragen Chastain has won ballroom dance competitions and run marathons; Mirna Valerio, known as “the Mirnavator,” is a fat ultramarathon runner and hiker; Jessamyn Stanley is a fat yoga celebrity, author, and fitness influencer; author and influencer Meg Boggs is a fat powerlifter; and Louise Green, author of Big Fit Girl, runs the Size Inclusive Training Academy to help personal trainers work with folks in all body sizes.

But few fat people compete at the highest levels of most sports. And maybe, sometimes, this is physics. But sometimes that “physics” has a very high human cost: “The body control piece is just seen as part of what has to happen at the elite levels,” says Pila. “When shaving a second off your time makes the difference between getting a medal or not, folks will say we have to look at every possible way of optimizing performance. This is what must be done, and sometimes mental health must suffer.”

And maybe, more often, it’s not physics at all but rather the larger athlete’s experience of anti-fat bias that keeps the doors to elite sports slammed shut. Because we see anti-fat bias emerge even in sports like shot put and powerlifting, where conventional wisdom holds that size equals strength, as well as football and rugby, where larger bodies are considered an asset, at least for certain positions.

Across the sports spectrum, fat athletes can expect to encounter locker-room teasing, size-based nicknames, and differential treatment. “Fat athletes may excel” in certain sports, writes Frankie de la Cretaz, a journalist who covers sports, gender, and queerness, in a 2022 article for Global Sports Matters:

But they are still overlooked when it comes to getting sponsorships. [ … ] Even in sports where fat athletes may contribute to a team’s success—like a touchdown made possible by the blocking of a lineman—it is never those players who are allowed to be the face of a team. The glory and renown goes to quarterbacks or running backs.

In this way, assigning kids to sports by body types doesn’t eliminate bias; it only narrows our understanding of what kids in different bodies can do. Laura, an attorney in Oakland, California, says people started asking if her now 17-year-old autistic son, Thomas, would play football when he was four years old. Laura is tall; Thomas’s dad is tall and bigger bodied, and Thomas, at 17, wears a men’s 3XL.

“He’s been way off the growth charts his whole life,” Laura says. And on many trips to the park or the grocery store, she could expect to hear a passing comment of “Get that boy signed up for football!”

Laura remembers touring a local high school when Thomas was in eighth grade and already over six feet tall. “The assistant football coach spotted us walking in the door and gave us this jolly but uncomfortably hard sell the whole time,” she says.

Thomas was flattered but also confused. He has never had any interest in football and views the constant commentary as “just one of those weird things adults always say,” much to Laura’s relief. “The risk for head injuries in football really concerns me,” she says. “But it is tricky because this is one of the few sports where a bigger body is celebrated and sought after. And that’s a different experience from other sports, where you’re just the big kid on the team.”

Within the field of kinesiology, scholars are divided on the question of whether the experience of anti-fat bias has a bigger impact than weight itself on a person’s fitness level and athletic performance.

“Some people see this as a social justice issue because if we’re not creating environments where all youth can feel empowered to participate, we are systematically keeping people from experiencing the benefits of the sport,” says Pila. “But there is also a camp that recognizes that, sure, at the participatory level, sport can be for everybody. But at the elite levels, exclusivity is a normative part of competing. So, we don’t have to change the system because only very exceptional people can get to that stage anyway.”

The problem with that latter argument is that “very exceptional” has always been code for thin.

“In many sports, we’ve never tried anything different,” says Voelker. “We haven’t allowed people of certain body types to excel and move forward to the next level. So, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that is far more about social construction than science.” We don’t even know what fat athletes can do at elite levels in most sports, because they never get there. And our resistance to changing is rooted in culture and emotion.

“There is often this sense that we have certain rules in place to protect the authenticity of a sport,” says Greenleaf. Consider the expectations around form and line for dancers, or the conviction of the head coach Natalie works with that he needs “long and lean” runners. “We hold on to these things as sacred,” says Greenleaf. “But rules change all the time.”

She draws a parallel with the long-running debate about the high rates of head trauma in American football: “We know football is dangerous for athletes. But when I ask students, ‘Could we create a form of football that doesn’t involve head trauma?’ they can’t wrap their heads around it,” she explains. “These are people who care about health! But there’s this huge disconnect.”

Meghan grew up in the dance world, taking lessons and performing from the age of five to 18, and says she spent most of those years justifying her own disordered eating habits.

These “rules,” which are traditions and rituals borne out of bias, may only apply in theory to elite athletes, but they absolutely ripple out and down through every level of competition. Meghan Seaman owns the On Stage Dance Studio in Stratford, Ontario. Even when placing dancers on her competitive team, Seaman never factors in weight. “If you’re willing to put in the work, I will find a place for you,” she says.

Her competitive dance team travels to five competitions and puts on two shows each year between September and May. At every competition, Meghan’s team of just over one hundred dancers, some tall, some short, some thin, some fat, line up next to teams where virtually every girl is five foot seven and weighs 100 pounds. “I feel like the impression of my team at dance competitions is that my studio takes it less seriously,” says Meghan. “Which is kind of true if [body size] is your scale. Nobody on my team would make it onto their team.”

Meghan grew up in the dance world, taking lessons and performing from the age of five to 18, and says she spent most of those years justifying her own disordered eating habits as necessary in her quest to be “a better dancer,” which meant having the ideal thin dancer’s body. “My experiences really shape the environment I strive to create for my students today,” Meghan says.

She prioritizes diversity when she hires instructors and trains the staff not to give compliments or corrections related to a dancer’s body size or shape. “There is a big difference between saying to a child, ‘Suck in that stomach!’ and ‘Your butt is sticking out!’ or saying to a child, ‘Lengthen your spine,’” she notes.

Meghan also gently challenges students who make fatphobic comments. If a student says, “I feel so gross in my leotard, I ate a huge dinner,” Meghan responds, “Good, you needed that dinner. You’re going to dance for two hours.” When she hears, “I’m too fat to be a ballerina, I can’t get my leg that high,” she explains why flexibility and endurance have nothing to do with body size.

To Meghan, this style of teaching feels worth it because it allows her to bring what she loves about dance to so many more students, even if she doesn’t have the glory of winning more competitions or sending students on to Canada’s National Ballet School. “The percentage of kids I teach that are going to have a career in dance is so minuscule, I would much rather focus on helping them have a good time, be active, and make friends and memories,” she says.

That’s true of all kids, in all physical activities. No matter how much thinness matters or doesn’t at the Olympics, most of our kids aren’t going there. And yet the sports leagues and dance classes we sign them up for are structured around the possibility that one of them might. That helps to justify training regimens and messaging that perpetuate anti-fat bias.

“You could say, ‘Well, let’s change the standards of this sport,’” Pila says. “But they land on, ‘Let’s change the athlete.’”

__________________________________

From Fat Talk. Used with the permission of the publisher, Henry Holt and Co. Copyright © 2023 by Virginia Sole-Smith.

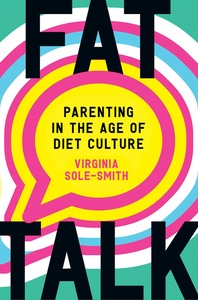

Virginia Sole-Smith

Virginia is a frequent contributor to the New York Times. Her work also appears in the New York Times Magazine, Scientific American, and many other publications. Fat Talk is her first book. She writes the newsletter Burnt Toast, where she explores fatphobia, diet culture, parenting and health, and also hosts the Burnt Toast Podcast. Virginia lives in New York’s Hudson Valley with her husband, two daughters, a cat, a dog, and way too many houseplants.