The 2020 Albertine Prize shortlist features stories of visceral excess and identity-seeking.

The voting period is open for the fourth edition of the Albertine Prize, an award administered by the French embassy that invites readers to choose their favorite work of translated Francophone fiction from the previous year.

The honorary co-chairs of the prize, author Rachel Kushner and literary critic François Busnel, led the staff of the Albertine bookstore and the book department of the French embassy in selecting the five shortlisted titles. The winning author-translator duo will share a $10,000 prize, to be awarded in December.

Last year’s winner, Negar Djavadi’s Disoriental, was among the best books I’d read in a while, so I was excited to see what 2020 had in store. The books don’t disappoint.

*

Animalia by Jean-Baptiste Del Amo

Translated by Frank Wynne

Grove Press

“She has a soft spot for the cows, however, because she milks them, squeezing the teats with dry hands she smears in butter. The end justifies the means, and she attaches little importance to the sexual appetites of animals destined for fattening or breeding.“

If Béla Tarr were to renege on his retirement from feature filmmaking, I would expect a book like Jean-Baptiste Del Amo’s Animalia to be the instigating factor. While reading it, in fact, I thought of the German writer Wolfgang Hilbig’s concealed knife of a book, The Females, as well as Tarr’s adaptation of László Krasznahorkai’s novel Sátántangó: long, bleak, enchanting assaults on the body.

It is perhaps a testament to Del Amo’s curation of detail, and translator Frank Wynne’s sharp, discomfiting translation, that there were numerous passages I had to skip over—not for lack of interest, but because they’d achieved their desired, alienating effect.

The book is an anti-Romance, a family story about four generations of peasants in southwestern France. The protagonist Éléonore is born into an economic situation as undesirable as the landscape she and her family inhabit (think of a Bruegel painting stripped of joy). Her mother, who Del Amo calls “the genetrix” is dejected and mirthless, much like her sick father. One almost wishes Del Amo’s writing wasn’t as visceral and, somehow, maximally spare as it is—you might otherwise turn away from the blood, bones, and excrement.

*

Hold Fast Your Crown by Yannick Haenel

Translated by Teresa Fagan

Other Press

“I didn’t believe in failure. Melville’s was proportional to the demands that motivated him: it indicated a secret glory. Society slaps the label of failure on anything that doesn’t respond to its demands. It denies success to anything that surpasses its set criteria.”

There’s something immensely satisfying about Yannick Haenel’s impassioned, funny novel, which begins with the search for a white whale (or, a white deer). That is, the protagonist is a writer who is set on finding a director to produce his screenplay about Herman Melville, the masterful writer who is mostly remembered for one thing, and who suffered throughout much of his life.

The protagonist decides there is no better collaborator than Michael Cimino, the American director who won multiple Oscars in 1979 for The Deer Hunter, only to follow-up his success by lobbing critical and commercial bombs.

The reader quickly understands that this is a story about everything and not very much at all, a man who seeks all kinds of truths and Truth, artistic freedom and the faith of his doubters. The narrator speaks so grandly that you might miss the occasional, critical details about the implosion of his personal life, his piss-poor drinking habits and other ironies scattered throughout this comic novel.

*

Kannjawou by Lyonel Trouillot

Translated by Gretchen Schmid

Schaffner Press

“In the evenings, after washing him and laying him down in clean sheets, his eldest daughter sets a glass of water on the bedside table, kisses him on the forehead, and says to him quietly as she’s leaving, I’m going to Kannjawou.”

With Kannjawou, Lyonel Trouillot, an acclaimed novelist and poet who writes in French and Haitian Creole, has written the kind of book that the reader in me loves most. Like Scholastique Mukasonga, John Edgar Wideman, or Patrick Chamoiseau, Trouillot has mastered the narrative of exodus, of looking forward as one looks back.

A short novel written as a young man’s journal, and populated with lively, efficiently drawn characters, Kannjawou celebrates Haiti as it was emerging from the 2004 coup d’etat that ended in the deposition of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The narrator and his friends are growing up quickly, and he must determine who he wants to be in relation to his small Port-au-Prince community.

Kannjawou speaks of class difference and community relationships. It is very much about life after something monumental, a grand novel about politics and the way a nation’s politics are mirrored in contained, interpersonal bonds.

*

Vernon Subutex 1 by Virginie Despentes

Translated by Frank Wynne

FSG Originals

“She is often depressed by young girls who look like Mormons or wear stupid veils. When it’s not religion, it’s family, or managing to remain a virgin until you get married. . . fundamentalist storybook romanticism. It’s like they’re determined to spend their lives making ragouts and tartes aux pommes.“

This is the other nominated novel that Frank Wynne translated, and that fact alone is pretty marvelous. There are perhaps no two books on this shortlist as diametrically opposed as Animalia and Vernon Subutex 1, at least as tone and style are concerned.

Virginie Despentes is a prolific novelist, screenwriter, and film director who spent time in the early 1990s working in a record store. She brings that experience to bear in Vernon Subutex 1, the first part of a trilogy about the titular, middle-aged man. Vernon himself once ran a music store. The rise of music streaming services throws him into a precarious economic situation. He is constantly on the verge or properly in the pit of loss, it seems.

If Animalia is a pre-industrial peasant’s garish nightmare, Vernon Subutex 1 is an epic of the post-industrial age, full of punk, sex, cities, and characters whose identities fluctuate.

*

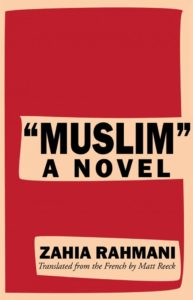

“Muslim” by Zahia Rahmani

Translated by Matt Reeck

Deep Vellum Publishing

In many ways, Zahia Rahmani’s compact book echoes Negar Djavadi’s sprawling Disoriental. The role of myth and archetypes, identitarian persecution, faith, movement through borderlands, naming, and the limitations and potential of particular languages all figure into this autobiographical novel.

The protagonist suffers a traumatic displacement, which accompanies her loss of the Berber language. What items or characteristics must one possess in order to prove who they are? Rahmani emphasizes the dilemma of those who are simultaneously stripped of everything and stereotyped, forced to carry labels and stigmas with them instead of a home place.

Aaron Robertson

Aaron Robertson has written for The New York Times, The Nation, Foreign Policy, and elsewhere. His translation of Igiaba Scego's novel Beyond Babylon (Two Lines Press, 2019) was shortlisted for the PEN Translation Prize and Best Translated Book Award.