Text to Speech Troubles: Why Writers Don’t Always Make the Best Speakers

Kate Greathead: “In writing, I have the time to consider my thoughts, figure out exactly what I want to say, and the best words to say it.”

Prior to the publication of my first novel, I was invited to speak at a conference for independent booksellers in hopes of generating interest in my book. “What do I do?” I asked my husband, who is also an author (a more veteran one) and much more comfortable talking in front of a group, and in the world in general.

“You say yes,” he told me.

Supposedly everyone is afraid of public speaking, but some of us have reasons to dread it more than others—in particular, a writer who is bad at talking. How can someone who traffics in words for a living be bad at speaking? Shouldn’t the two go together?

I am not fast on my feet when it comes to extemporaneous speech. I wouldn’t even say I’m of average verbal dexterity. My awareness of my clumsiness exacerbates the problem. My sentences are often derailed by anxiety as I…um, you know what I mean? I have a terrible habit of allowing my voice to trail off while searching the listener’s face for signs of affirmation. People often finish my thoughts for me.

How can someone who traffics in words for a living be bad at speaking? Shouldn’t the two go together?

According to my dad, my first semi-complete sentence, at the age of three, was in response to the question, Why don’t you talk, Kate? “Because I don’t talk good.” I hate being this way. It’s incredibly frustrating and disempowering, and it makes me feel stupid and meek.

It’s made me a writer. In writing, I have the time to consider my thoughts, figure out exactly what I want to say, and the best words to say it. I can come across as I don’t in life: assured, articulate, dignified.

The conference was months away, and there was plenty of time to figure out what to say—and to practice saying it. But every time I sat down to do this, I was paralyzed with fear. The mere thought of standing up before a room of strangers and talking about my book elicited the kind of terror that manifests on a primal, cellular level: dry mouth, racing heart, that sour, mammal-in-danger armpit odor.

It felt like a test. I’d managed to write something people had decided was a book; now I had to pass as an author. A real author wouldn’t need pre-written notes to talk about their work.

“I’ll just wing it,” I told my husband the day before the conference when he asked what I was going to say.

“Maybe you should write down some talking points,” he suggested.

That was a good idea. I jotted down a few broad themes to hit upon.

The event was held over breakfast in the conference room of a hotel. I had no appetite. Four other authors were speaking, and I was slated to go last.

I knew I shouldn’t look at the other writers as my competition, but I couldn’t help it. Apart from being eloquent, each of them seemed so comfortable up there at the podium, talking about being authors and about their books.

The guy who went right before me was a children’s book author, but he could’ve pursued a career as the star of a children’s television show. He had that kind of charismatic charm and presence. The audience loved him.

My turn.

I introduced myself and my book. “It doesn’t really have a plot,” I said of my novel. “It’s just a portrait of a mother-daughter relationship over the years.” Registering an apologetic tone in that statement, I clarified that this was intentional, rather than a failure on my part. “I really love Mrs. Bridge by Evan S. Connell,” I explained. “I wanted to write a book like that.”

Hands now trembling, I glanced at my talking points:

-mother-daughter novel

-no plot, more a portrait of lives over years

-Mrs. Bridge

I’d already covered the entirety in four forgettable sentences. The next few minutes went something like this: I’d have a thought, start a sentence, but then I’d forgot where I was going, or the point I was making suddenly seemed stupid or obvious, and my voice would peter out. I was reminded of a time I’d once accidentally shifted into neutral while driving on the highway and it took me a little while to notice. To repeatedly push the accelerator without accelerating is a terrifying, hopeless feeling.

If you’ve never stood before an audience of independent booksellers as you struggle to speak a coherent thought, imagine a sea of the kindest, most empathetic faces you’ve ever seen, nodding along encouragingly at every sound you manage to produce, regardless of its intelligibility. You’d think this would put me at ease, but it had the opposite effect. I felt their anxiety for me, their profound discomfort, and that deepened my own. I felt guilty putting everyone through this.

There are things we can overcome, and things that make us who we are.

It could not go on. “I’m sorry,” I said after an especially long pause. And then, in what I thought of as a face-saving act of mercy for all of us in that room, I told a lie: “I’m ten weeks pregnant and I’m suddenly feeling very nauseous.” (I was indeed pregnant, but only eight weeks, and I felt completely fine.) There were steps leading off the platform, but in the throes of fight-or-flight, I simply leapt off. As I wove through tables toward the exit, about a dozen women rose from their chairs and followed me out and into the restroom, where I locked myself in a stall and made gagging sounds. I had to carry through with the performance.

When I returned to the conference room my husband was standing at the podium wrapping up the speech I was unable to deliver. The independent booksellers thought this was very sweet, and he received a big round of applause. Afterwards I found myself surrounded by well-wishers, congratulating me on being pregnant, praising Teddy’s speech, and expressing their excitement about the book.

But I didn’t feel right about it. More than deceitful, the experience left me feeling cowardly. There’s performance anxiety, and then there’s something else. I will never talk good—or fast and fluidly. My brain just doesn’t work that way.

The baby I was pregnant with is now six; an observant, deeply feeling boy who, like me, expresses himself haltingly. His younger sister is another story. Words tumble out of her mouth in rapid succession, sometimes faster than I can keep up with. “She’s so quick!” people say. How I longed to be described as such when I was younger. But there are things we can overcome, and things that make us who we are. To be a person who is not trying to pass for anything more than who I am—this is who I now aspire to be.

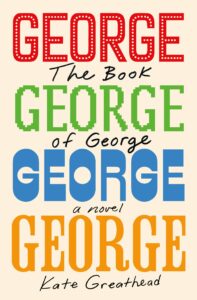

My second novel is coming out this fall. So far I haven’t been invited back to the conference of independent booksellers, but if I were, I have some ideas of what I would say.

This time, I’d put it all down first on paper.

__________________________________

The Book of George by Kate Greathead is available from Henry Holt & Co., an imprint of Macmillan, Inc.

Kate Greathead

Kate Greathead is the author of Laura & Emma. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, and on PRX’s The Moth Radio Hour. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband, the writer Teddy Wayne, and their children.