The following selection of terrible writing by otherwise great writers (Daniel Clowes, Isaac Fitzgerald, Gillian Flynn, Damian Rogers, Mac McClelland, and Steve Almond) appears in Drivel, a project of LitQuake, edited by Julia Scott. Someday we’ll release all the alternate designs for Literary Hub (one of which featured an animated wagon wheel).

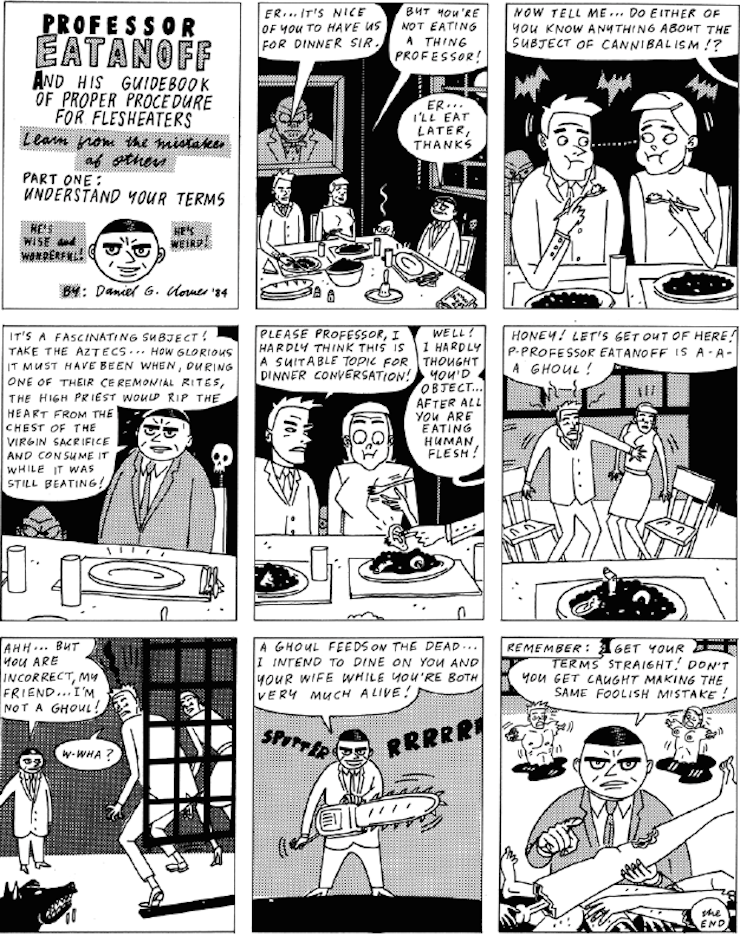

Daniel Clowes

Professor Eatanoff (And His Guidebook of Proper Procedure for Flesheaters)

Daniel Clowes is the acclaimed cartoonist of the seminal comic book series Eightball, and the graphic novels Ghost World, David Boring, Ice Haven, Wilson, Mister Wonderful, and The Death-Ray, as well as the subject of the monograph The Art of Daniel Clowes: Modern Cartoonist, published in conjunction with a major retrospective at the Oakland Museum of California. He is an Oscar-nominated screenwriter; the recipient of numerous awards, including the PEN Award for literature, Eisner, Harvey, and Ignatz; and a frequent cover artist for The New Yorker. He is married and lives in Oakland, California.

* * * *

I wish I could just write this off as mere juvenilia, but I was actually twenty-three years old when I created this tasteful gem, a year shy of my first professional work. I did this strip, along with several others of equal merit

(Doctor Motherfucker, I Married a Human Worm) with the intent of selling them to National Lampoon magazine, or possibly even the New Yorker (!), imagining in my youthful delusion that America was secretly clamoring for passive-aggressive adolescent cannibal humor. I actually put this page in my illustration portfolio, which would probably explain why I never got a single assignment.

–D.C.

Isaac Fitzgerald

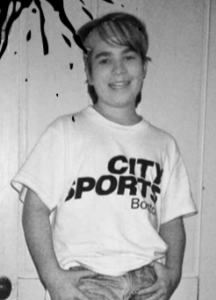

Eighth Grade Journal

Isaac Fitzgerald has been a firefighter, worked on a boat, and been given a sword by a king, thereby accomplishing three of his five childhood goals. He has written for the Bold Italic, McSweeney’s, Mother Jones, and the San Francisco Chronicle. He is the books editor for BuzzFeed.com.

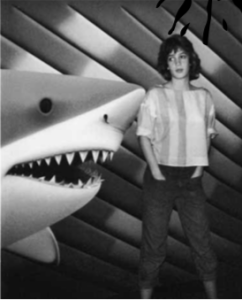

[Note from Isaac’s mom, Susan: “Sagging neckline on T-shirt denotes his chewing on collars is still an oral pastime. (Not yet smoking???)]

* * * *

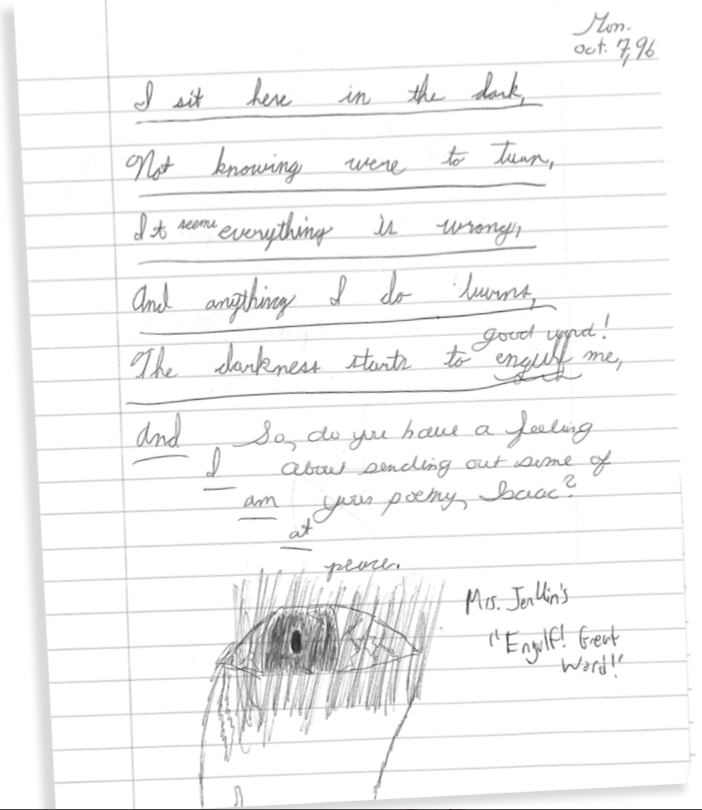

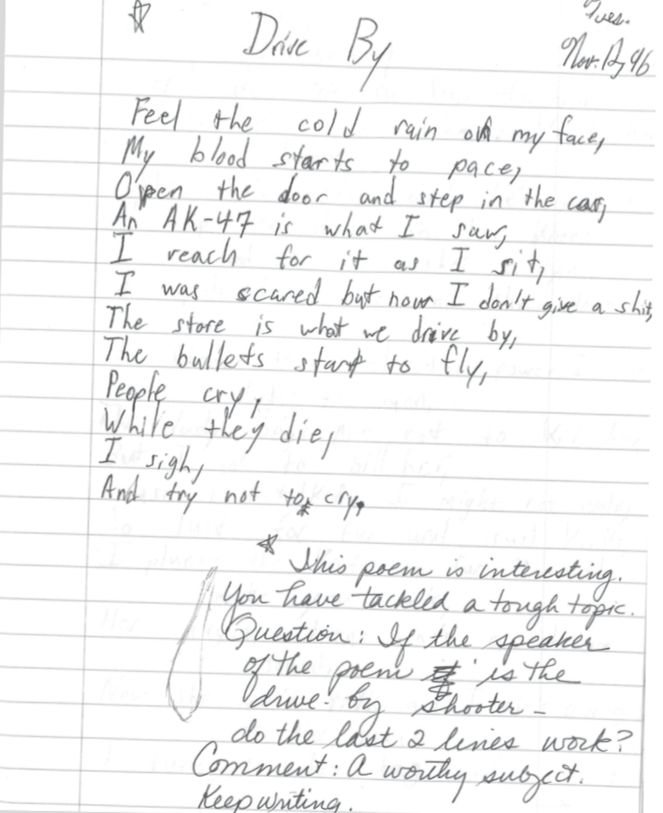

This is something I wrote for a class, which meant that in eighth grade I was handing it in to a teacher after every entry. And her name was Mrs. Jenkins, and she would then write comments. Don’t forget—that’s me in the photo. I’m an adorable, happy little kid.

Here’s how Mrs. Jenkins started the journal: “Keeping a daily journal is very helpful in learning to become a better writer. Remember that you write best when you are interested in, and know something about, the topic you choose to write about. Think about the events and interests in your life. I am looking forward to writing and sharing with you this semester.”

Clearly she had no idea what she was getting herself into. My journal quickly filled with drawings of hangmen and pentagrams on fire, poetry about drive-by shootings, and rap lyrics by the Beastie Boys.

No matter how bad it got, Mrs. Jenkins heroically tried to keep a positive outlook on my “art” by praising my vocabulary, poetic form, and attention to detail.

–I.F.

Damian Rogers

Persephone

Damian Rogers was born and raised in suburban Detroit and is now based in Toronto, where she occasionally writes lyrics for Canadian troubadours. Her first book of poetry, Paper Radio, was nominated for the Pat Lowther Memorial Award. She is the creative director of Poetry in Voice/Les Voix de la Poésie, a recitation contest for high school students in Canada, and the poetry editor at House of Anansi Press. She has been preparing since the 1980s for a cameo in a Jim Jarmusch film. He still hasn’t called.

* * * *

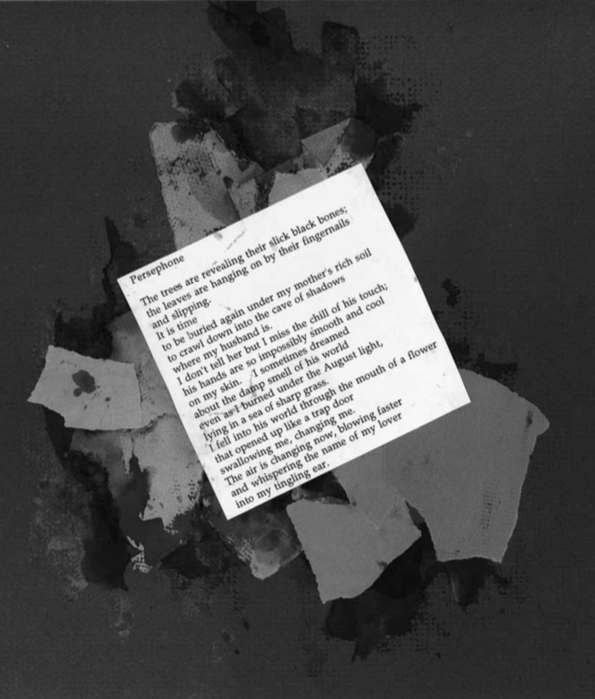

I asked my friend Brett if he had a copy of one of my terrible high school poems (he’s a natural archivist, so there was a chance), and he came back with this thing that I’d completely forgotten existed. Oh, where to start? I was so proud of this poem that I rubber-cemented it onto purple—purple—card stock, which I carefully decorated with paint splotches and torn paper. Note also the jaunty placement of the poem, which further reflects my artsy instincts.

The poem itself is a classic undergraduate study of the moody, vain, self-involved drama queen (a self-portrait, naturally), all erotic innuendo and vague feminist subtext. I was obsessed with the Persephone myth, and as far as I knew, I was the only person who had the bright idea to mine this material in the first person. An innocent young girl married to Death! So sexy!

The first thing I notice about the poem is the fact that I just scissored the thing right up to its margins, revealing how little feel I had for how white space operates in a poem. (Perhaps, though, this was an echo of the claustrophobia Persephone endured in the dark and crowded Underworld? Yeah.) Also, I’m not sure the line breaks could be made any less effective than they are here. My favorite worst line is the portentous “It is time” hanging there all by itself. I bet I loved that. And I doubt I could craft a flatter line than “where my husband is.”

The phrase “whispering the name of my lover” makes me shudder now, as I remember a friend from university bitingly noting, “Damian never seems to have boyfriends, just ‘lovahs.’” I can’t even believe I’m admitting to that in print. The shame is so intense. Additionally, the references to a “cave of shadows” and “mouth of a flower” places this work within the fine tradition of Magic Vagina poems.

I do have affection for this earlier self; I must be gentle with her. She was so unsure and awkward and so hopeful to fit in with those who don’t fit in. And the presentation’s craft-project, ersatz-zine aesthetic is pretty cute.

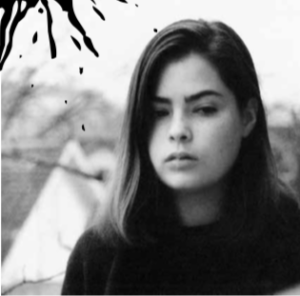

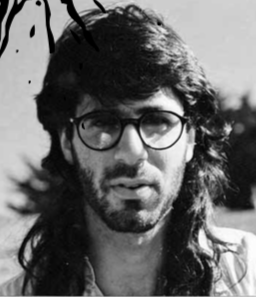

Getting back to vanity, I’m trying so hard to look like I’m living in a subtitled movie in this photo. It was taken on the fire escape of the hippie cooperative house where I lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the fall of 1991. I was really into rocking “the French inhale” during this period. Oh, my Gauloises, there is no pretention like that of the nineteen-year-old would-be poet. As you can clearly see behind my head, the last leaves were holding on by their “fingernails.” And you know . . . slipping.

–D.R.

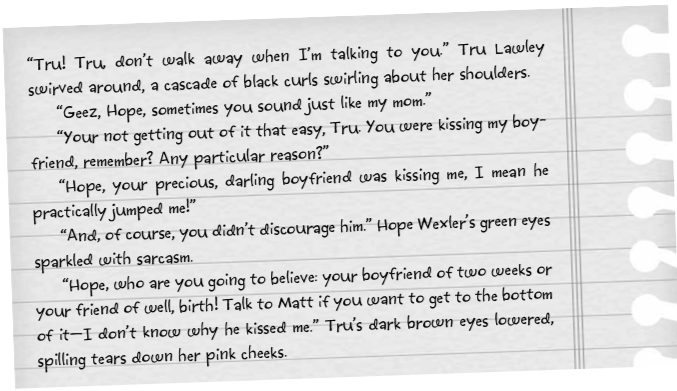

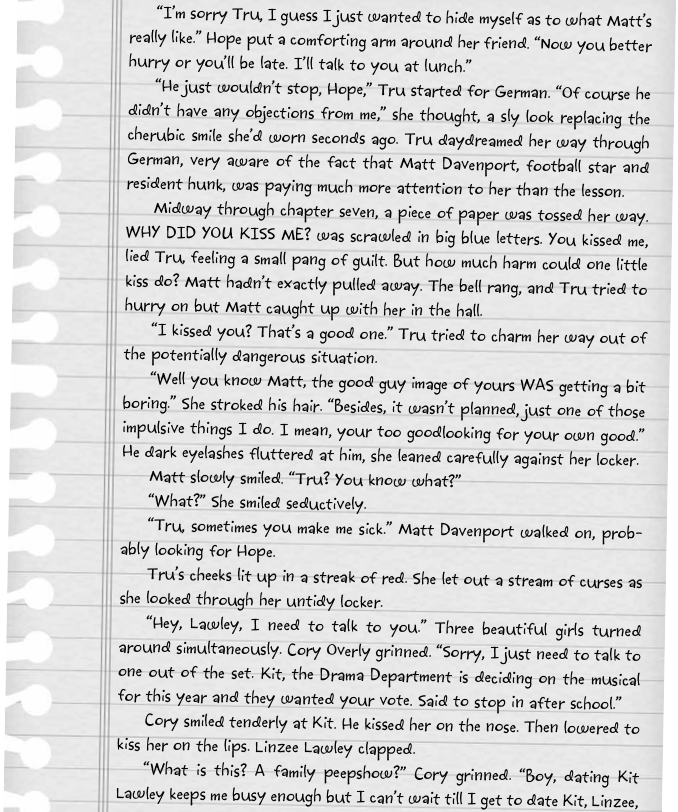

Gillian Flynn

Trouble at Osage Lake High

Gillian Flynn is the author of Sharp Objects, Dark Places, and the number-one New York Times bestseller Gone Girl, which has sold more than six million copies worldwide. She is also the screenwriter for the film adaptation of Gone Girl. Flynn lives with her family in Chicago, where she may or may not be hoarding every single original paperback of Sweet Valley High ever.

* * * *

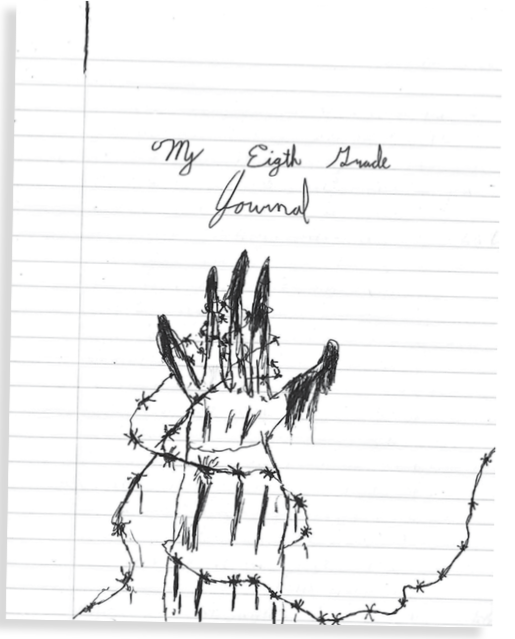

In junior high, the primary topic on my mind was figuring out How to Be a Cool Teen. I know this because in the same ancient Garfield Trapper Keeper in which I unearthed “Trouble at Osage Lake High,” I found a self-improvement list titled “Changes.” Some useful entries: “Hair: Buy and experiment with mousse.” “Conversation: Think of interesting things to talk about. Listen to friends’ conversations. Practice.”

Yes, I was a painfully shy kid, and so I looked for guidance in books. Specifically, that soapy staple of the 1980s: the Sweet Valley High series, which beckoned readers to follow “the continuing story of the Wakefield twins—their laughter, heartaches, and dreams.” It was basically Dynasty in high school. Actually it was better, because it starred good and evil twins. (Is there anything more satisfying than good and evil twins? We’ll answer this question shortly.) Jessica Wakefield was the wild one (on the illustrated cover, her blond hair is moussey-loose over her jean jacket) and Elizabeth was the nice twin (her blond hair clipped back in sensible barrettes). I was obsessed with Sweet Valley High—reading the books wasn’t just fun, it was obligatory prep work. What I learned from them was that my high school years would revolve around cheerleading, being beautiful, betraying friends, and fighting over boys. Cool!

Naturally, they influenced my burgeoning career as a writer. (Was I a “Jessica” or an “Elizabeth”? The fact that I was in eighth grade and launching my own book series probably answers that question.) So, in answer to the earlier query: Is there anything better than good and evil twins? Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you: good, evil, and goodish-evil triplets! Sit back and enjoy “the continuing story of the Lawley triplets—their bickering, kissing, and . . . German lessons.” With my apologies.

–G.F.

Steve Almond

To the Men at Work Outside My Window

Steve Almond is the author of ten books of fiction and nonfiction, most recently the story collection God Bless America. His memoir Candyfreak was a New York Times bestseller. His short stories have appeared in the Best American and Pushcart anthologies. He lives outside Boston with his wife and their three kids, none of whom are bad poets. Yet.

* * * *

I’m not sure where to begin. This poem is like a very serious cancer, or perhaps several cancers at once. Or maybe it’s my way of announcing that I deserve cancer. It’s hard to say anything definitive amid so many bad judgments. Witness this narrative of cultural encounter in which the effete, lonely Bad Poet typecasts the working-class palookas in a manner that is at least as bigoted—more so, actually—than the targets of his princely consideration. Upon further review, this “poem” is not only self-aggrandizing and pretentious (hell, that’s just the color of my ink, folks) but demeaning and oddly homophobic. I’m just that good.

I do remember the episode that triggered this poem’s composition. I was around 35, living in Somerville, Massachusetts, and trying to be a writer. I was lying in my bed, depressed, again, when a fleet of workers turned up to tear apart the backyard of the house I was renting. This was all being done at the behest of my landlord, a monumental American who blew through his mortgage loans with a dizzying and tender devotion to personal bankruptcy. Trucks he bought and canoes and boats and race cars whose monstrous flatulent engines he revved at all hours outside my bedroom, with its dark wainscoting and low beams.

Was there anything I might have said to these guys beyond the obvious? That I was lonely and inept, that I envied them their camaraderie, their masculine competence. That I viewed them as stand-ins for the brothers whom I had resented and pined for throughout my childhood. It was their fault (the brothers, the workmen) that I felt weak and effeminate and unworthy of love. It was their fault we destroyed one another. It’s always someone else’s fault. That’s the lesson history teaches the aggrieved, over and over.

“Is there nothing between us besides cocks?” That’s an illicit wish posing as an indignant question. But the Bad Poet has no access to the mysteries of his internal life, so he settles for bad jokes about classic rock and fake lyricism. It might even be ok to pity him, if he didn’t so obnoxiously assert pity as his birthright.

–S.A.

To the Men at Work Outside My Window

See here, fellows: It is me, your skinny-stemmed little daisy faggot boy

Yoo-hoo! Yes, me—the fellow you keep glaring at.

I have a few things to say, if I might.

Might I? Right, then: first off, let me accede to the discrepancies

between us. I did not just recently fall from the turnip truck,

or what have you. I can see, from the cut of the collective jib

out your way, the paintsplat and jeanrip, those ungodly scabs,

that we are not destined for tea,

okay? Understood. Capiched. Comprendo’ed.

There are divisions here deeper than language, or drill bits

Yes yes. We would tire of one another in a matter of minutes

You would bang and I would frill

bang bang

frill frill

And never the twain shall meet

But say: since you have knocked me awake and into this dew-clingy day

I find myself gilding a few questions

As in: all that banging and haranguing

is it all entirely necessary to the repairs you have been summoned here

to enact

And: why are you all named Richie?

Is there some sort of law—the law of Richies?

And: why all the niggers and spics and chinks and so forth

Some of my best friends, you understand,

they are niggers and spics and chinks

and they know how to use sanders, some of them

And the cadences of your speech (which are rhythm type things)

How do you do that, each and every day,

murdering all those syllables?

Are you aware that the letter “r” is still in wide use?

And classic rock?

How many times the rising sun and the hotel in California and who,

precisely, is wrapped up in that goddamned douche?

Don’t you ever feel just a bit numb?

Don’t you ever get tired of your tools?

Don’t you ever, in some secret sun, sit in wonder of the leaves?

or the women you undress around your offbrand cigarettes

Is it all just sawdust and Sheetrock?

Is there nothing between us besides cocks?

And what lies beneath all that sun-puckered skin?

Can your blood, ever, be had by something less than knuckles?

Mac McClelland

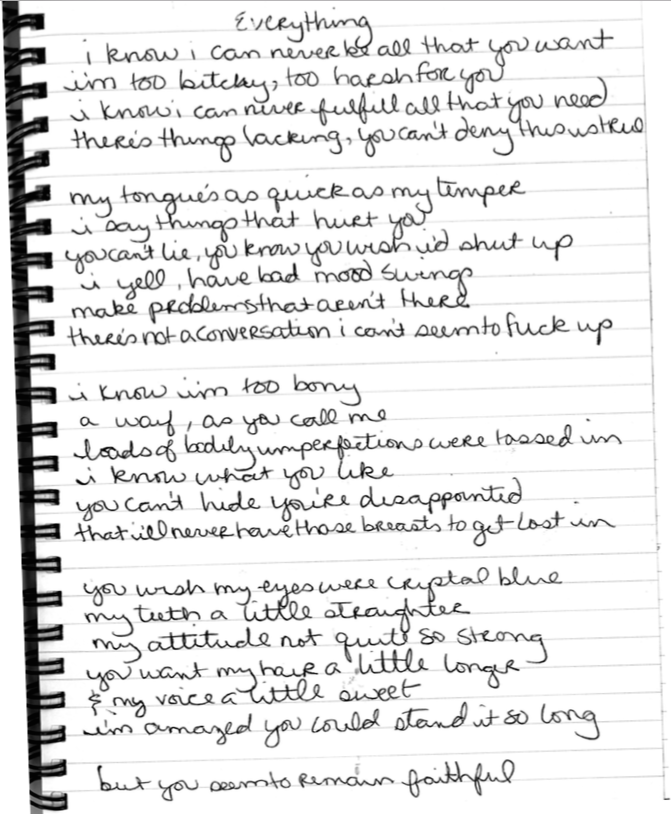

Everything

Mac McClelland has written no poems as an adult, but as a magazine writer has won awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, the Hillman Foundation, the Online News Association, and the Society of Environmental Journalists, plus she’s been nominated for two National Magazine Awards and her work has been collected in The Best American Magazine Writing, The Best American Nonrequired Reading, and The Best Business Writing anthologies. She has written two books, Irritable Hearts and For Us Surrender Is Out of the Question. Her website is mac-mcclelland.com.

* * * *

As my memories of how painfully shitty my high school poetry was are pretty intact, I actually refused to look at the journals I handed over to Julia Scott for Drivel; I only skimmed this entry, with my hands covering my groaning face, because she forced me to, and only enough to see that in it I projected all the insecurities that television had projected onto me, directly onto my then boyfriend. I wish the brilliantly titled “Everything,” written when I was 15, could have been, as it first appears to be, a screed against Chad (who in fact, if you called him even now would tell you, thought I was the very picture of teenage perfection) for not being able to handle me and/or accept me in all my rough, natural awesomeness. Alas, ew, it’s a thank-you note for his deigning to date me. As a lot of people never outgrow that mind-set, I guess this “poem” could make me grateful that I got over that, but mostly, it makes me want to die, and never think or talk about it again, so if we ever meet on the street, please do not bring it up.

–M.M.