Terrance Hayes on Shakespeare, Ol' Dirty Bastard and What Makes a Good MFA

The Author of American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin in Talks to Jeffrey J. Williams

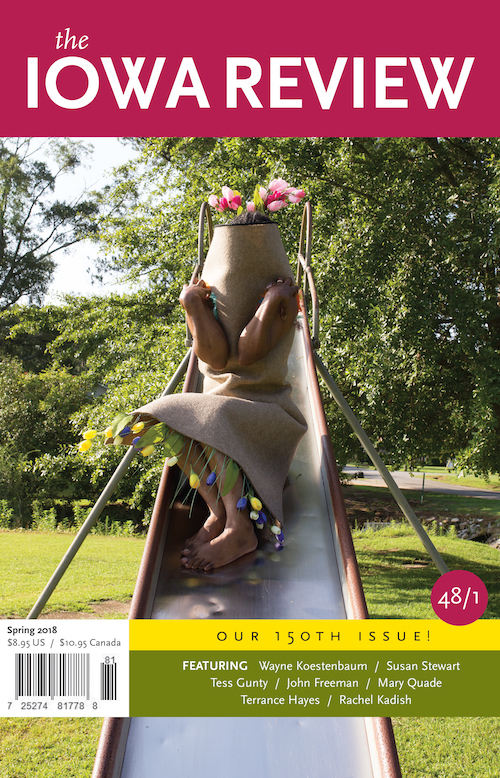

The following interview appears in the Spring 2018 issue of The Iowa Review.

![]()

Terrance Hayes is one of the most celebrated poets of his generation. Currently a MacArthur Fellow, Hayes synthesizes disparate elements in his work: classical forms like the sonnet; popular culture references from hip-hop to Scooby-Doo; comments on race, especially African-American experience; modes such as the Japanese business presentation slide series pecha kucha; and reflections on fatherhood and family. As he remarks in this interview, he resists being tied to one adjective to describe himself as a poet.

Since graduate school, Hayes has published a steady stream of books, beginning with Muscular Music (Tia Chucha Press, 1999; reprint Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2006); Hip Logic (Penguin, 2002), selected for the National Poetry Series; Wind in a Box (Penguin, 2006); Lighthead (Penguin, 2010), which won a National Book Award; How to Draw (Penguin, 2015); and the forthcoming American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (Penguin, 2018). He received a MacArthur Fellowship beginning in 2014. Born in 1971 in Columbia, SC, Hayes’s mother was a corrections officer and father a military barber. He attended Coker College on a basketball scholarship, but explored painting and poetry and, encouraged by an English professor there and the poet Toi Derricotte, went to the University of Pittsburgh for an MFA in Creative Writing. After that, he taught in Japan, at Xavier University in Louisiana, and from 2001 to 2013 at Carnegie Mellon University. He is currently distinguished professor of English at the University of Pittsburgh and also distinguished visiting writer at New York University.

This interview took place on June 24 and July 1, 2016, in Pittsburgh.

![]()

Jeffrey J. Williams: You use a variety of forms, you sometimes draw from popular culture, and your poetry changes from book to book, so it would be hard to define you as one kind of poet or from one school. How would you characterize your writing?

Terrance Hayes: I have a line in the last book about how to draw an invisible man, and it says, “I’m trying to be transparent.” I don’t actually want to be invisible, which is the dilemma of people of color, but I would like to be transparent, so people can see what my issues are, good and bad. I just try to be transparent and very present, and then see what happens.

JW: Where would you place your work? Sometimes it seems like the New York School, but at other times, it’s very different.

TH: It’s true, I do like O’Hara, I like Berrigan, and I actually like Ashbery, too. The New York School poets are interesting to me for their immediacy; New York School culture is about being present and being in the moment.

But I think it is my personality that I can pretty much go into any room where people speak English and navigate around that room in terms of engaging with what they’re doing. When I’m at a conference that’s full of formalists, they say, “Oh, you’re a formalist”; if I’m at an African-American retreat, people say, “Yeah, you’re an African-American poet.” I’m interested in form; I’m interested in culture. Depending on what space I’m in, depending on what kind of water I’m in, people see me in very different ways. But for myself, I try not to think about it too much. The other thing is what the pronoun “I” does in my poems—is it a confessional “I,” an intellectual “I”? People come up to me saying, “You know, I think of you as a confessional poet.” That’s OK, too; I think the word means to be opened up. As a student of poetry, I find that confessionalism is a great tool that fiction writers don’t have. (Nonfiction writers maybe do, but they are a prisoner to it.) Everybody assumes that the “I” is a confessional “I,” and they assume that with me, but I find it’s a useful device so I can lie to people in plain sight. Sometimes it might be confessional, but I do like to make stuff up. It frees me up to tell the truth. So when my mother saw my earliest poems in the first book, she was like, “Oh, it was just your imagination.”

JW: Like the poem about her pulling a gun on you, “Late”?

TH: Yeah, but it’s not always just my imagination. It allows me to not get too caught up in terms of privacy and secrecy across the poems. It gives me a way to not be limited.

I’m interested in Language School poetics, too. The idea that language in and of itself is a material or communicates sound that is a material—that interests me. I’m a student of poetry, and I feel like everything’s on the table, and I can use it all. I don’t necessarily have to commit to one circle, even though I feel people pulling me, “Be on my team, be on my team!” and I’m not sure if I want to be only in your part of the house.

JW: Do you think it’s because you had an anomalous path coming into poetry? You come from a small town in South Carolina and went to college because you had a basketball scholarship. You were outside the main academic pipeline and didn’t have a silver spoon. Maybe it’s generational, too. You’re not as fixed in one position. According to the sociology, boomers are more fixed in their positions and more polemical, whereas Generation X is more polyglot and less oppositional: they tend toward what one sociologist calls “the cultural omnivore” and don’t have as strict distinctions among kinds of art.

TH: That’s a great question. I was born in ’71, and we had multitasking and were in the electronic age. But now there’s digital or social media, which people like my daughter are very aware of. (I’m one of the few people I know of in my cohort that doesn’t do social media. I used to do it, but it was taking up too many of my words.) I do think that the phenomena where you have access to all of that information makes you polyglot. You know a lot of things, but you haven’t spent a whole bunch of time in one area.

JW: One downside with the glut of information now is that there’s no stable core of references. It seems like, at midcentury, whatever limitations they had, they had a common idea of literature, which probably valued highbrow modernism, whereas now it’s much more disparate and up for grabs.

TH: You get that with students. They sometimes say, “There’s all this new work, and you’re still trying to make us read these old white dudes from the canon.” Last year at Yale, some students protested, saying, “Why do we have to read all these white guys? Why do we have to read Shakespeare?” I know because an article came back to me that said, “You should read Shakespeare and Terrance Hayes.” I agree with that, and I don’t see why it can’t be both.

I’m interested in Shakespeare, but especially how Shakespeare is in conversation with Scooby-Doo or The Walking Dead. You find that out especially as a teacher. I was just doing a Q and A and bouncing between The Simpsons and Picasso. It was a room of low-residency MFA people in Tampa, and I said, “Half of you are going to get what I say about abstract expressionism, cubism, Rothko, and Picasso, and half of you are going to get The Simpsons, Lil’ Wayne, and Future, this new rapper.” Why do I have to separate those out?

“My grandfather was a war veteran; my dad was in the army; my brother was in the army. And yet I still feel like there’s something wrong with trying to force me to support the troops.”

Future has this song “Fuck Up Some Commas.” He’s talking about money, but when I hear it, I hear it about syntax and the way a sentence is built. It’s like James Joyce and Molly Bloom and a fifty-page sentence—James Joyce really fucked some commas up. So why would I have to segregate them? Why only Shakespeare, when there’s this other stuff that’s happening? I think for younger people especially, everything is so simultaneous now.

Some of my undergraduate students don’t know that there is another way of learning. Sometimes black students and female students will say, “They didn’t teach black writers,” or “There weren’t that many women.” And I say, “Right, but that’s the symptom of their era; now it’s a new era, but it’s not like we can just forget the canon.” If a kid says, “We don’t need Mark Twain,” I say the canon still has to be folded in. It’s not like you could move something out just because it happens to not look like you. You can read Toni Morrison and still read Shakespeare. They’re different, but you also find that they’re still gold.

To go back the other way, when I’m talking to someone who’s sixty-five, and I’m making a reference to Future and saying it’s a song about strip clubs, I’m still saying it’s interesting. “To fuck up some commas” is an interesting idea. I’m not asking to get rid of Bach and Beethoven and only to listen to this knucklehead from Atlanta. But it so happens that there’s something in his music that can be of interest to how we work—especially to a room of writers or people who think about language and literature.

JW: Is there a tension between form or aesthetic value and identity? There’s an assumption in contemporary literature that writers represent their identities.

TH: I’m interested in identity, but there’s another circle that’s closer to the self, and that’s personality. Part of my personality, certainly, is because I’m black, and I’m Southern, and I’m male. But there are also parts of my personality that just have to do with some weird thing my mother said to me or that I sat on the lap of a woman that couldn’t speak at a piano when I was three years old.

How you get fairly boring poems about race is because you are trying to plug into some notion about identity, as opposed to some notion of personality. Race might be part of my identity, but it’s not the only thing that’s there. To me, personality is getting close to something like transparency.

When I think about the Black Arts poets, people like Baraka, who I knew and hung out with, or Sonia Sanchez, to me the great tragedy is that there’s this wall because they’re interested in blackness and uplift and a certain kind of identity, but I get no sense through their work of their personality. It’s like your grandfather worked every day at the mill, but you never knew what his favorite color was, or what cruel thing his mother said to him when he was ten years old. That’s what I find interesting, and to have that wall stops it.

That gets back to transparency. All my flaws and quirks and neuroses, they fit just as well as the scarring that comes from racism or masculinity, and I don’t want to have to cut that off. People confuse privacy and secrecy way too much. I’m not saying it’s confessional, but it gives more texture to your work if you can figure out how not to close off those rooms.

JW: Do you consider yourself an African-American poet?

TH: Yes—and many other things. I don’t think anybody is just a poet with no adjectives. I wouldn’t limit it there: I would say, yes, I’m African-American; yes, I’m Southern; yes, I’m male; yes, I’m hip-hop; yes, I’m neurotic; yes, I’m a bastard poet. It’s all these other things and the more, the better. The order of those things shifts depending on where I am that day: some days, I’m a male poet first, and that’s what’s really going to inform the work; a lot of days, I’m a black poet first and that’s what’s going to inform it. But I don’t want to be tied to one adjective.

Poetry is the end for me. It’s always what I go back to, and everything is filtered through that. I would say, first, that’s who I am. But I don’t think that’s always true for other people.

JW: If I were to periodize your work, I’d say there are three phases so far. In your first book, Muscular Music, you play with popular culture, but there’s a stronger sense of self in your last two books. In the second and third books, Hip Logic and Wind in a Box, you’re experimenting more with form, whether it be the sonnet or other patterns of repetition. They’re also about identity, and some of them talk about race explicitly. In your most recent work, in books like How to be Drawn, you have poems like “Gentle Measures” where you’re figuring yourself out and thinking about fatherhood. It seems more ambivalent, too.

TH: “Gentle Measures” almost went into Lighthead, but I just didn’t have it finished. It’s a pecha kucha, a Japanese form. In the most general sense, my deepest ambitions are for the poem as a puzzle, as an object, as a Rubik’s cube to play with. My deepest ambition is always for the poem, but the growth comes from trying to not get stuck as a human being. So I would hope that in my forties I would be different, more interesting, and know more—and probably be more ambivalent—than I was in my twenties.

The last poem in Hip Logic, “The Same City,” is about my stepdad and about the way I appreciate this man who’s raised me. And I thought, after I’d written it, “Well, if I don’t go out there and find this dude who’s my biological father, I’m going to keep writing this poem.” So that’s a personal thing from my life, and if I didn’t answer that life question, I felt like I was going to be stuck in my work.

Then, finding him in my forties, and becoming somewhat ambivalent about what that means. It’s in Lighthead, and that poem is in conversation with “The Same City,” about meeting this man who is my father, where he says to me, “God made nothing sweeter than pussy.” The growth of the poems is very local, and when they become confessional, it’s because I’m trying to become someone better from one day to the next, or come to terms with the ways I can’t be better from one day to the next.

That goes back to transparency. I don’t want there to be a great distance between me as an individual walking down the street and in the poems, because they feed each other, and one illuminates the other. I’m not doing enough as an individual if I’m not seeking out new experiences, new people, being challenged, being honest with who I am, or my poems are going to be stuck.

I don’t think Ashbery thinks that. I think he could just sit down, listen to some music every day, and feel like he could make an interesting poem. That might be true, but I think for the last ten or fifteen years, Ashbery wrote the same book. That’s a nightmare for me. I would not want to do that—although maybe I will when I’m eighty. I need the tension of asking myself day to day, “Is that what I think?” Maybe that’s what gets called ambivalence or curiosity or even just playing—and it was different when I was in my twenties.

JW: You’ve had plenty of critics comment on your work, but if you said there was a quality that it has, what would it be?

TH: The thing that is always a challenge from one poem to the next is managing time. Where there’s an experience, I’m thinking: Is this going to be converted to a lyric moment? Or am I going to break a line here? What’s going to be left out? What’s going to be the rhythm of my sentences?

The joke in my classes and in my household is that I am always timing and measuring everything. To go back to your point about the later books, in Lighthead, the first poem begins with a line, “I could never get the hang of Time,” and the epigraph is a Borges quote from “A New Refutation of Time.” At some point I realized, even more than fatherhood, even more than parents, even more than race, the thing I’m really obsessed with is measuring time.

That’s manifested in the pecha kucha poems in Lighthead: they’re not measurements of meter; they’re measurements of time. It’s twenty seconds for each stanza, and I’m trying to create out of these twenty-second lyric bursts a narrative that holds together.

JW: I can see how you’re a time poet rather than a space poet. What do you think is a flaw of your poetry?

TH: That’s an interesting question. Allen Grossman said, when people ask, “What are your poems about?” he says, “Poetry, the subject is always poetry.” I find that to be very useful as a maker of poems, even though that’s frustrating for readers. So if someone asked, “Are you writing poems about race or Pittsburgh?” I’d say, “No, I’m writing poems about poetry.”

“I’ve always had a sense of moving into spaces where I felt a little bit different. Whether that’s a black barbershop, or working as a temp in an office, or working in a warehouse, I always felt there was nobody in that space like me.”

But if I find a flaw, I feel myself coming up against a statement like that. I want to be writing about something; I want to have a subject like novels can, capturing a whole world. When I’m writing poems, I can get an immediate pleasure but still feel like there’s something on the other side of that, which is what I go to novels for, like One Hundred Years of Solitude. I feel like that’s something I can’t do: the canvas is not big enough to fully capture consciousness in a poem.

And I think, if I was really trying to fully capture consciousness, I would have to leave poems. There’s some moments in David Foster Wallace’s nonfiction, like “Consider the Lobster,” that do it.

JW: I like the essays more than the fiction.

TH: Me too, because there’s too much affect in the fiction. In those nonfiction pieces, he’s totally present, and I’m totally with him; I’m totally in his head. I feel like that’s what I aspire to. In my body of work, that’s what I’m aiming for, and I never can get it. I’m chasing it. I think about the next poem, because I’m always thinking I could do better, and have I done the best I can? I don’t know; I hope not. That’s how I work, from one day to the next. The best stuff still hasn’t happened.

As a poet, you know your limitations, and those limitations are the form of the person or the poet. So that’s my big question: am I the one that’s limited and there’s a way to do this thing, or is it the genre that’s limited?

In Wind in a Box, I decided the only way to get into a poem was as a puzzle that was going to come together, so the great revelation was all the boxes in the book. I wrote them one at a time, and there are six, because a box has six sides. What’s important for me in that book is the joining of it, making this new object. Then in Lighthead, there’s a lot of fire throughout the book, so I’m playing around with the paradox of fire and lighting things up. After I’ve done a poem, then I can think about it as a piece of the puzzle and as a part of this whole thing, as opposed to writing one poem at a time, and when I get to twenty poems or forty poems, I have a book.

So what’s useful about the Allen Grossman line is to say, what is the puzzle about? Are you making a landscape or a figure drawing when you put the puzzle together? And his answer is it’s just language, it’s just poetry. I think that’s useful, but on the other hand, it’s not quite satisfying for me. I still need it to be more relevant, and the stakes have to be a little deeper.

If I switch metaphors—and I’ve had this argument with Mary Karr—it’s like if you make a meal and your audience is waiting to eat it, but when you put it on the table, they have to watch you eat it. That would be the Ashbery kind of poetry. It’s a great meal, and maybe you’re a terrific eater, so they watch and wow, those noodles look delicious. But Mary’s attitude is that, if you never get to eat it, you’re like the cafeteria worker, which is why she does not like that kind of poetry.

My attitude is to split the difference. I’m going to starve if I don’t eat it, but if I don’t eat it, neither should you. Don’t you want to see me eat it too? That’s the Stephen King end of things. So I feel like, if I’m going to make a meal, we’re going to sit down at the table and eat it together. I am interested in whether you’ll like it or not, but if you say, I like your steak but don’t like the beans, all right, eat the steak, and don’t eat the beans. I’m going to eat it the same. I want us to enjoy a meal together, and I can’t say it’s only for me, even though there is a part of me—and this is what I like about Ashbery—that says, if you don’t like it, that’s your problem. Eat something else. I’m always torn between the dilemma of saying there has to be something worthwhile to someone other than myself, even though I can get pretty far just eating what I make for myself and having no one else at the table.

JW: And the decision is how big the table is. It could be an enormous one, or it could just be a small table.

TH: That’s Baraka. Baraka would say your obligation is to feed black people. If other people are eating it, that’s fine, but this is your job. But does that mean I’m only making black-eyed peas and collard greens? What does it mean to say only certain people? I like a little sea bass, too, or a little halibut.

So for someone to say this is your audience and you have to give people the thing they’ll really eat, I’m saying you don’t know what people’s capacity is. Maybe they’ll like caviar, maybe you’ll like octopus. Or maybe they won’t. But I’m still trying to get people to the table. Who those people are, I don’t really think too much about that. I don’t think about everybody that looks the same; I don’t know who those people are, but I’m going to feed them.

JW: And it’s also the table to come, which you can’t quite predict, or you might be totally off if you do.

TH: The other side would be the question of failure. To stay with the food metaphor, you can make something bad. If you’ve got a restaurant and you’re McDonald’s, you can’t sell sushi, you just make burgers. My interest is not what people expect from me as a poet; I know I can make burgers, but can I make sushi? Maybe I can, but I need to try that.

That goes to the question of how much you allow yourself to fail in your day-to-day practice. Certainly, after enough books and enough acknowledgments, are you still comfortable with failing? Thelonious Monk says there is no failure, there’s only rehearsal and practice. That might be a better way of thinking about it. You write a poem, and you think it’s a failed poem, but maybe it’s a draft, and you just keep going onto the next poem. The thing that limits people sometimes is that, at a certain age, they start to say, “This is what I do.”

The desire to want to feed people is not a bad desire. It gets into the art for art’s sake versus social purpose argument, but I think the real purpose is who do you want at the table with you? Reasonable people do want somebody at the table with them; there’s something wrong with the image of me sitting at the table and people watching me eat. For me, that wouldn’t be enough.

“I’m not that interested in anything other than making something, playing with something, and it doesn’t have to be anything other than poetry.”

With success, you get encouraged to think, “I’m so special that people will just watch me be me.” So when Pacino starts being himself in his movies and stops acting, people accept that and say, “Oh, it’s Al Pacino! That’s great!” But I still want to see him be somebody else. There are people that, when someone becomes a celebrity, they just say, “It’s enough if you write it, and it’s just something you’ve written, we’ll take that.”

JW: I want to come back to how you reflect upon your own success, but first I want to ask about your relation to art. I know you paint and have for a long time. In fact, you were a painter before you were a poet. How does that bear on your poetry? Do you see paintings as a puzzle?

TH: I feel limited as a painter. I can do pretty good figurative stuff—Lucian Freud is my man. In this studio class that I’ve taken, the teacher had a joke that I should take pictures of my paintings, because he would come over, and I would have a painting of a boy, and he would go away, and then an hour later it would be a painting of a tree, then he would go and come back and it would be a painting of a shoe, and it’s still the same canvas. What I would say to him is that I was just trying to build up a surface. What I hate is a white canvas, and I don’t like one layer of paint. I like the texture of it, so the only way to get to that is to keep painting stuff and erasing it, and painting on top of it and struggling with it so the layers would be hidden.

I feel like this is true in the poetry process. I’ve been talking for a year about this poem that I started in 2009, and in 2013 I printed it out and it was 244 pages. It was sort of like Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, but it wasn’t working and it wasn’t good, so I stopped and finished How to be Drawn. Then last summer, in 2015, I pulled it out again, and I was like, “Okay, I’m going to get these pages down to sixty pages. I think there’s a good book-length poem in here.” But I still couldn’t do it. When I worked on it, after not having looked at it for two years, I decided it was still bad, and I was cool with that. I thought, “Maybe I’ll look at it in a little while.” That’s about failure and practice. It’s okay if I spent all that time on this manuscript, and it is, by some terms, a failure, but by other terms, it’s going to lead to something at some point. It’s still an open-ended process.

What’s great about painting is that all the different things get absorbed, and then there’s still a result. Even if you can’t see underneath all of it, I know that there’s a face of a boy and that I’ve built it up. So in the last year or two, I did take pictures of the paintings going through these various stages. Maybe the one that’s covered up is more interesting, and maybe the last result is sort of a failure, but that’s all right, I’m still going through the process.

JW: Related to art, there’s been a lot of critical writing about postmodernism and different kinds of theories, and you mentioned Benjamin. Are there particular ideas that you gravitate toward or that have influenced you?

TH: The most basic one is Hegel and the dialectic. I’m a dialectical thinker. I learned this stuff in college, and it has become one way for me to understand what metaphor is. Thesis, antithesis, and synthesizing—that certainly is my way of being in the world all the time. So, if I’m talking to someone, and I mention Glenn Gould and Future, or Picasso and Lil’ Wayne, my mind is always bridging those two things. Or in a poem I’ll talk about Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Othello. Bridging those things is my natural way of thinking, and I think of that as a collage. I’m mostly interested in philosophers that have an interest in language—Wittgenstein, even Nietzsche.

JW: I can see that in your poems. Sometimes they seem eclectic—with references from pop culture to high art—but your motivation is toward synthesis. It’s not necessarily thesis and antithesis, but several things that you might bring together. You’re a synthetic poet.

TH: I don’t know how negative that is. I have a friend who’s a critic, and he said that my work was an anthem to ambivalence. I can put things together and see what is made without having to choose. Years ago, I was on a panel with a guy who is a political and social poet, and he said to me, “You know, at some point you do have to choose sides.” Why? To me, the conversation is done once I choose a side. So maybe that’s a form of ambivalence.

I’m not that interested in anything other than making something, playing with something, and it doesn’t have to be anything other than poetry. But then there is that other part of me that walks up the street and watches CNN and hears stories, and it is true that I inhabit this world and want to respond to that.

JW: You do sometimes talk about race and recent politics. I like the poem where you play off the line “Thank you for your service.”

TH: “Support the Troops!” The poet I mentioned who said you have to choose a side, it’s not like I disagree, it’s just, why would I rush? So I’ll risk naivety in the moment. He’s an older, white dude, and he was saying that he had been a victim of molestation, and he said, “Once you’ve seen what real evil can do in the world, you know you don’t have the luxury of saying, well, Hitler was a painter too.” So I said to him, “I actually don’t disagree, I just feel like I could be naïve for a while and pursue truth, and at the end of that, if I see something that’s evil, I will say it’s evil. If I see something is wrong, I will say it’s wrong. But if I don’t know that, then the poem will also be about that; it will be about not knowing.” That’s a better way of being an artist to me; that’s a more interesting artist who doesn’t know and is pursuing an answer versus an artist who does know.

JW: So your obligation is to ask questions?

TH: Maybe a satirical question like in “Support the Troops!” where I’m asking, why should I support them? My grandfather was a war veteran; my dad was in the army; my brother was in the army. And yet I still feel like there’s something wrong with trying to force me to support the troops. That poem is also a conversation about whether you have to choose a side. And there’s a lot of ways to choose a side.

JW: I want to ask about your background and how you came to do poetry. On the one hand, it seems like your career was accidental. You told me another time that, when you were growing up, you didn’t know if you’d become a corrections officer like your mother or go into the military like your stepfather, but you came to poetry while you were in college.

TH: Or I might have become a high school English teacher. Growing up working class and not having anyone who had ever have gone to college, I didn’t have an extreme pressure. My father would say, “You’re going to go to college—you’re smart.” But they didn’t have any savings. My good fortune was that I was tall, so I played basketball. I was a visual artist, too, so I got offers from Savannah College of Design, but they didn’t have any sports, and they didn’t give me enough money.

I also was in track and field. I don’t know how many people know this, but I was on ESPN for the National Scholastic Indoor Track and Field Championships. I did high jump and the four-hundred-meter relay. I got letters from LSU, Clemson, UNC Chapel-Hill, but no one gave a full ride. Track teams are so big, they don’t usually give them. It’s not like the basketball team. So I didn’t want to have to pay anything, and because of my background, I had no sense that people went to college if they didn’t have their own money.

JW: So you went to Coker College because they gave you a scholarship in basketball?

TH: Yeah, a full ride. In basketball, I was fine. I couldn’t do Division I, because I would have been a guard, and because I’ve been this tall since I was fifteen, I’ve always played inside, so I never really learned how to handle the ball. So for basketball scholarships, it was going to be D-II or D-III, and I thought that was the only way I was going to go to school. Because I was lucky enough to get a scholarship, my parents didn’t feel compelled to tell me what to do. My dad said, “Maybe you should major in business.” If he had said that when I was eight years old, I probably would have done it, but it was too late. I also thought that, when I finished, I would just go back home. I didn’t know what happened on the other side of college. I didn’t really know any college graduates other than my teachers. I thought, maybe I’ll teach, and if I didn’t teach, maybe I’ll go work in the prison. I had no sense of what kind of avenues might open up.

In my ignorance, though, that meant I was majoring in fine arts, and I was taking writing. I’ve always had a sense of moving into spaces where I felt a little bit different. Whether that’s a black barbershop, or working as a temp in an office, or working in a warehouse, I always felt there was nobody in that space like me. So I just accepted that. Everybody has their own weird thing, and mine is that I like books. Every time I tried to bring it up with my friends, they were like, “Man, what are you talking about?” I didn’t expect everyone to want to talk to me about it. So I just accepted that. When I got in, the joy of college was my teachers. I knew I could talk to this professor about Faulkner because he was teaching it. Or Toni Morrison. I’d already read their books, but now I had somebody to talk to.

JW: When you went to Coker College, you went for visual arts. I think I read somewhere that you only took one creative writing course.

TH: Right, Intro to Creative Writing. It was with a professor who was the first person to say to me, “This is something you could do.” He has passed away now, but he was a good friend. He was the type of professor whose house you’d visit, and all my family had met him before he passed. His name was Jack French, and he actually called up Maya Angelou for me when he was trying to convince me that I could do this. He had been in Vietnam, and I think he worked as one of JFK’s speech-writers or something like that, but he had left all of that and had this big horse farm in Camden. He was a Yankee and he was generally bored and impatient with everything about the South, but he liked me and he thought I was special. It was my first time hearing it. I always thought I wasn’t that much different from anybody else.

JW:: How did you end up at Pitt for grad school?

TH: I’d majored in fine arts, and I’d been encouraged as a painter for a long time, since third grade when I started in the art club, so I always thought that was something I could do. I could just write a poem for the fun of it, but I’d spent all this time as a painter, and my art teacher, who’s also passed away now, Kim Chalmers, certainly encouraged me. He was very direct about what he thought my potential was. But when the time came and I looked at studio arts, I couldn’t afford it. In my last year, I had done a series of paintings on ceiling tiles. The reason I used them is because I could get a big box of tiles for like five dollars. In that box, there were twelve twelve-by-twelve tiles, and once I put some gesso on one—it was smooth, and I could paint on it. Then I stood them up, and I had a grid of images. They all had faces of oranges in them and a bunch of other stuff. It was because I couldn’t afford a twelve-by-twelve canvas for each of the pieces.

So I really could not afford to do the kind of art I wanted to do in graduate school. Even though I had not done that much poetry, it seemed cheaper. Then when I got a fellowship to the University of Pittsburgh, it really seemed cheaper. Another one of my English teachers had gone to Pitt in the sixties, and he talked to Toi Derricotte, and she talked to me and told me to apply.

Then Toi, it just so happened, was reading in South Carolina around the time I was thinking, “Can I really do this?” and I went to the reading and met her, and I decided I was going to. Which is really lucky. I also thought, if it didn’t work, I could just go back home and get a job there. I think that’s a working-class outlook: if it didn’t look like it was for me, if I felt in the workshop the way I felt in the barber shop, I could just go home and work. I would do what everyone else does.

When I’d go home, all they said was, “Why are you still going to school?” And I would say, “You’re not paying for it.” Most of the time, I was going to leave. Then it was three years, and I was done.

JW: What was it like when you were in grad school? You obviously did OK, but how did it go in the program?

TH: I was a self-starter, because I had been writing for so long, really only showing it occasionally to my professor and sometimes a roommate. But I had gotten into a habit of working as long as I wanted to on my poems. I didn’t write a lot of poems as an undergrad, but I was always working on them. I read “To Autumn” by Keats, and I was like, “This is blowing my mind! It’s so erotic!” And then for the next year, I was working on a poem that was totally a Keats imitation. Because I wasn’t in a class and didn’t have to turn it in at the end of the week and revise it and turn it in again in a portfolio at the end of the semester, I could just work.

I had another poem about my father working in the yard called “The Earth God,” and I worked on it for about two years. Both of them were in the packet I sent to get into Pitt. I also sent in stories—it was an MFA in creative writing, not just poetry, and I didn’t know they had different sects.

The challenge for me in grad school was other people’s timelines. I thought, “Wow, a poem a week?” Even now, I really don’t show people stuff when I’m working on it. I’d rather take a year to figure it out than have you tell me in five minutes what’s wrong with it. I have to trust my own perception as opposed to waiting for someone to tell you how to fix it, which is what happens in an MFA program.

I was in a space where people had read lots, and I felt like I had to go to the library and read everything in it. In fact, I tried to do that, all the contemporary poetry books and the books on the Pitt Press, because I assumed that everybody else had. Of course I was wrong, but it’s become a practice that I’m still trying to read as much as I can. Especially in poetry, although the joys are when it’s not poetry. But the big challenge was other people trying to tell me how to fix the poems.

JW: One complaint about creative writing programs is that they routinize the process and produce cookie-cutter writing, but the university also allows a lot of people to write and do things like that.

TH: One thing that people say is that we’re creating robots, and students are just writing the same poems. But I’d say that’s always been true. When people read Sylvia Plath, everyone wanted to write confessional poems. There have always been mediocre poets and a large number doing the same thing. I don’t think the number increases or decreases the potential for finding real brilliance in the pool.

If we’re talking about class, the people who could survive as poets before were people who were wealthy already. That’s Wallace Stevens or T.S. Eliot, so the model for the poet who lives as a poet would primarily be rich white dudes. On the other hand, it’s romantic to assume that you’re going to be poor. Are those our only options? Either you’ve been born into wealth, or you’re down-and-out in the gutter, like Charles Bukowski, doing terrible jobs? Both of those are equally romantic and equally problematic.

What we can say now is that at least there are more people with opportunities. People can come and sit around and talk about work. The problem is what to do with them after that, if they can’t get a job teaching?

JW: It’s hard to get around the question of jobs and the shrinkage of the academic profession. How do you see that affecting creative writing programs?

TH: The thing that I appreciate with an undergrad is the freedom of writing and not connecting that to professional aspirations. Some of them want that, but they don’t know what it looks like or know enough about the template for becoming a successful writer, so they wind up writing really interesting things all the time.

On the other side, a graduate student is so close to the professional world that they can’t help but have those things influence them. What you find with the typical grad student, even on the first day, is they’re thinking about books and concepts. I don’t work like that, and I don’t think that’s the best way to open up one’s creativity, so I’m telling them that I’ve gotten here by just keeping my nose an inch from the page. And you can’t force anybody to accept your art; you can’t make people take the food that you’re giving them.

My approach to life and my work is not strategy. I’m someone who wants to experiment and play and see what happens, because it’ll be new no matter what it is, which is probably why I can’t write a novel. I think a novelist has to be a strategist of sorts and think “this is the general structure I’m working out.” That informs my teaching, too, and that could be a problem for an MFA student or a young poet who wants a strategy and says, “Tell me how to become a successful writer.” I’d say, “I believe in experimenting, and some experiments succeed, and some fail.”

People from the outside sometimes look at me and look at how things are going, and they say, “You were very strategic. How did you get here? How did you win this?” And I say, “I didn’t predict any of this.” With each book, I think every poem is the last poem, every book is the last book. I don’t necessarily think I’m entitled to anything or that I can control very much.

JW: There are more than four hundred creative writing programs in the United States. There are no doubt different kinds of programs, but what do you think makes a good program, and what makes a bad program?

TH: Flexibility is what makes a good program. The university space should be, ideally, a fluid space, but instead we often encounter people saying, “This is at the top of the pyramid, and everything else is beneath it.” I think that a good program values Language poets the same way they value Black Arts poets and confessional poets. You can insert anything in that but certainly fluidity in terms of faculty and aesthetics. It’s important that new things can show up, as opposed to things that shut doors and segregate people. Responding to the person in front of you and their potential and interests, and challenging those potentials and interests, seem to me benchmarks for a program.

But students often don’t want that; they want a strategy for how to make it in the academy. If you’re just trying to make art, nobody has to buy what you do, and the world doesn’t need it, so I try to tell them to relax. You have to be adaptable. Could you run a press? Could you do community workshops? Could you be a high school English teacher? Could you get a job for a company using your skills with language? When you look at all of the MFA programs, very few offer alternatives other than looking for an academic job, but I say to folks all the time, “It is not your only option.”

JW: What makes for a good workshop?

TH: Most workshops are set up around strategy, but they’re not set up around failure. You work on the poem, you bring it in, and people say this is wrong, here’s a strategy on how to fix it. My skepticism around strategy is that it doesn’t have room for failure. So an experimental workshop asks, “Why were you trying to do this? Maybe you’ll try this?” And maybe we’ll generate poems that aren’t done or finished, but at least we’ve made something new. That is what I value in a workshop.

I’ve realized that my students definitely need to be praised and encouraged, but my method goes back, again, to the way I write my own poems. I just want to be writing, and I don’t care that much if you say you love it or you hate it. My default answer to just about everything in the world is, “Man, I’m just going to go write a poem.” When things get rough, whether it’s grading student papers or paying the bills or a fight with my wife, my default answer is to write a poem and just forget about all of it. That’s my attitude in the workshop, too. The challenge is to convince students that that’s viable.

JW: College was pivotal for you, and you work in a university. What do you think universities can do?

TH: What I think the university can do is bridge the things we’ve been discussing; it can bridge James Joyce and Future. But you have to know what kids are responding to. The university seems to be fairly fixed and stable, where James Joyce is more important than “Fuck Up Some Commas.” But for me, the university is as fluid and as responsive as the culture is.

I think what young folks recoil from is when they show up and say, “I was just listening to something interesting,” or “I just saw something interesting on my Twitter feed,” and older folks say that’s not important. My sense is that the synthesis is what the university can do. It can synthesize historical knowledge and research and contextualize those things, because it’s happening right now. Students should be able to bring us the now, and we should be able to bring them the research and the history, and then that middle ground is what the academy is.

So my definition of the academic requires a little outside information. That means if you’re reading a poem that has a reference to Ol’ Dirty Bastard, that’s an academic poem, because not everybody will know who he is, and you have to go research. But then there are the poems that are just about feelings and about family, and maybe you don’t have to have a dictionary or internet next to you. Those aren’t academic poems. My point about the academic is not about high or low, it’s just that there’s outside information. I say to students that it’s fine to not know stuff, but you have to research everything. That’s what the academy is: knowing how to find things you don’t know, as opposed to “these are the things you should know.” And to me, academic discourse is about making connections and contextualizing.

JW: You have a significant position now—you won the National Book Award in 2010, and you’ve won several other awards, and you got the MacArthur in 2014. Every time I’m flying out of Pittsburgh, I see your picture in the airport, with Pitt advertising, “Come study with a genius.” How do you feel about your position? On the one hand, people must want things from you. On the other hand, it has to be gratifying.

TH: Once your picture is up at the airport, there’s always people making proposals to you about what they think your name could lend to their ventures. But I want it to yield something for my primary concerns: teaching and writing poetry. My job in the university is simple: I’m a teacher. Anything else connected to that is just gravy. I did help start the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics, which is important in archiving poetry, but most of my concerns, over eighty percent, go toward teaching. How can I be a better teacher? How can I make my students better equipped as writers or readers or whatever?

For my poetry, I haven’t had the prize that makes me feel like I’m secure and don’t need to write another good poem. I haven’t seen that prize. There are people who have achieved more than I have, like Nobel laureates in literature, but still, there’s no guarantee. So I operate in the long view: whatever prize I get today doesn’t guarantee a real legacy. My legacy is still in an upward arc of poems, so people can say, “I didn’t know he was going to do that. I didn’t know a poem could do that.” I continually want to make the last poem more interesting.

I was wired that way from the outset, as a college kid without any concern with where it was going to go or who was going to like it. Part of that is just obsessive-compulsiveness, which may be in my personality. That has helped me deal with the success, because the success still feels very ephemeral or temporary, and it certainly hasn’t helped me write poems. I understand that people around me think that my involvement in a new center will be a good thing, but I say, “Well, how does a MacArthur make me a better poet?”

Some of the resources available to me now allow me to put myself in new situations, but that has never been my ambition. I’ve always tried to stay very focused in terms of what I need to write. A little bit of reading, talking to some people about art and how art works—those are things I know work for basic stimulation. I could talk to myself in a room and come up with something, but I wouldn’t want to only do only that.

__________________________________

From the Spring 2018 issue of The Iowa Review.

Jeffrey J. Williams

Jeffrey J. Williams’s most recent book is How to Be an Intellectual: Criticism, Culture, and the University (Fordham University Press, 2014). He has conducted more than sixty full-length interviews, published in Minnesota Review, Symploke, Contemporary Literature, and elsewhere. He serves as one of the editors of The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism and is professor of English and literary cultural studies at Carnegie Mellon University.