Before the book, I was poor. The other side of a welfare worker’s desk kind of poor. In order to receive assistance, you have to be small and needy. I would make my case and yet not speak up for myself. The seat on the other side of that desk feels like silence. In order to break away from that place and such silence, I wrote a book.

The book did well enough that I see staged photos of its cover on influencers’ Instagram accounts, next to cold brews or succulents, and I receive royalties twice a year that are enough to buy a vehicle with, or pay off debt, or support my family for a year. With my first royalties, I thought I could restore myself, or reconstitute all the things that had been stripped from me, after years of being without. I thought I could bring people back or keep them here.

I remember when the first wire came; it was $50,000. My husband and I just stared at our bank account.

“We’re going to see Rhonda. We’ll head out tomorrow,” I said.

“Sure,” he said, without reluctance. He knew how important my best friend was, and how sick she had become. She had been in the hospital for months by then and constantly messaged me to say she was feeling better, not to worry, and that she’d be out any day now. I was used to her being sick.

She had Crohn’s disease and was always in and out of hospitals, taking treatments, sometimes steroids. The year before, she had reconciled with the fact she wouldn’t be able to have kids because of the disease. But it wasn’t a fatal disease, from what I could research. There was always the idea, in my mind, that she couldn’t die from this illness, that its complications are rarely fatal. There was also the idea that something as good as $50,000 would rub off on my entire surroundings, and that things might be better for the people around me, for good.

With my first royalties, I thought I could restore myself, or reconstitute all the things that had been stripped from me, after years of being without.We went to see her—my two boys, myself, and my husband—we all got in the car and drove 15 hours to see her, from Indiana to San Antonio. During the ride, I looked up florists and planned how I would fill up her hospital room with flowers. The kids were excited to see her and were kind of glowing with a playful, joking joy between each other. My eldest was happy we’d be staying at Rhonda’s house, because he loved her pool, and her husband, Robert, and her brother in-law Mike and niece Mia, who all lived there. Every year, my son and I would visit in May so the whole family could hang out for Rhonda’s birthday. I was mostly excited about the idea of bringing flowers to Rhonda. I had been sending them monthly via online order, but they never looked as impressive as they appeared in the pictures advertised. I would finally have a chance to pick the flowers out myself.

Somewhere between Indiana and Texas, in the midst of the excitement, there came a small revelation, that I could do more with my money to help someone: Shawnee Inyallie, a Native woman who went missing close to the Indian Band I grew up on. I had seen her “missing” poster for a few weeks. The faces of missing women are always on my social media timeline. For Native women, we go missing at alarming rates, and experience sexual violence at a rate, in some communities, ten times higher than the national average, so our timelines are full of “missing” posters and news reports of violence against people we know.

Shawnee was 29 and looked like a cousin of mine. Her cousins were my best friends growing up. That’s how I came to see her poster. My friend Kristie asked everyone to share the poster, so I reached out that day to see if I could put up a reward to find her. Her family thanked me for the offer and directed me to the RCMP, the Canadian police in Hope, British Columbia, where she went missing.

When I called, the police were mostly unhelpful, telling me that I could make a poster myself to advertise the award, and that if they received a tip, they’d pass along my information to receive the money. During my drive, I made several calls, and my brother was able to make the poster, and within an hour we were up and sharing the news of the reward. It was liked and shared more than a thousand times, and it gave me a lot of hope along that drive that maybe money could solve problems like these. Maybe money, and placing a monetary value on a woman’s life, could help find that woman, and things could be different with the more money I made.

We stopped at a hotel, and I watched as the shares grew. I slept easy that night, imagining tomorrow would be good for the kids, that a woman might be found, and I let myself be a little naïve. I didn’t think about the danger in naïveté, when my whole life I had been aware of it. Something about having money made me less sharp—duller and simpler.

“Do you ever get survivor’s guilt?” a Native woman asked me in Duluth recently, at a book event. I had just read for the Indian college there, and she was part of a group of women, the Kwe Pack, who are runners and all successful women in their own rights. The women had become artists and worked in politics, and they all told me similar stories about how guilty they feel for having things in life. Even having an iPhone brought them guilt. I understood, because we see so many people who don’t survive. It’s hard to enjoy anything when you think about the people who won’t get to know a life away from pain or struggle.

My answer was complicated. Their answers were complicated. We all want better for ourselves, for our children. But we leave people behind. We can’t take care of everyone. Our mortality rates, the statistics over our heads, and the burden of a history of colonization weighs on us.

Maybe money, and placing a monetary value on a woman’s life, could help find that woman, and things could be different with the more money I made.Rhonda experienced a different life from me. She was white. It always made us laugh that we got along. I am hypervigilant and scared of white women. They usually hurt me, or hurt my money, or put me in vulnerable positions at work. I’ve learned to avoid them, and sometimes resent them. It’s hard to say that to you, because you don’t know me well enough to like me, or see beyond the worst of me. I can tell you, though, that Rhonda changed people for me—all people.

When I met her, I was an editor for the student paper at a community college. It was a slow crawl to a life in academia. I had received my GED a couple years before. I had to work hard to understand the function of grammar, or how to construct a sentence, and I didn’t spell well. It took all of me to learn it and become an editor. She came into my tiny office at the college with her husband, Robert. He didn’t speak. She did.

She was blond, blindingly white, pearl white, with something illuminated inside of her. Blue-eyed. The things I am not. I resented the lightness of her. She smiled when she spoke. Asked perceptive questions, on behalf of Robert. She was barely 19. She wanted Robert to write for the paper, for college credits. He stood silently, smiling in a pleasant way, pretending to listen to me while Rhonda took notes.

His first assignment was a baseball game. He was supposed to cover the opening game. When Rhonda sent me the story, I knew she wrote it. I line-edited it, harshly, and sent it back. She came to the editing room for real-time feedback. Back and forth, we fucked with each other. Until we saw the ambition in one another. We saw the desire to be better. She was living on her own because her home life was difficult, her relationship with her father was nonexistent, like mine—her father was part-Indian, like mine. He was a drunk, abusive, like mine.

I didn’t find this out until later, but I sensed her hard life. At the time, I was confounded by her bubbly nature. I didn’t think it was possible to be so positive and strong. And she spent a lot of her time trying to show me that things could be better, and that a positive attitude wasn’t unnatural. It was a solution in her mind, I think.

But the part of me that had been a foster kid, who didn’t like to make eye contact, who was on welfare, who had to fight for things, like bus tickets home, or food, or a bed—that person was afraid of her. The part of me who was radical, like my mother had been, didn’t believe a white woman could understand me. The person who was a child, who invited a white girl to my house once, and the girl called home immediately—that child was scared, inside of me. But I relented.

I had to let Rhonda love me. She moved to San Antonio as I was finishing up at community college. She sent for me. She visited me. She called. She messaged me. She was like me, in that she took care of multiple people. During this time, she encouraged her husband to become a nurse practitioner, to go to school, and she moved her niece and brother-in-law in while her sister was in rehab, recovering. Rhonda wanted to take care of everyone.

During this time, I was taking care of my eldest son, being a single mom, helping out family back home when I could, sometimes receiving help myself. It was hard, but necessary, to live away from my community, and Rhonda was always there. We struggled together, me talking about moving away from my rez to make something of myself, and her talking about how difficult it was to be something like married, when she had never seen a good marriage in her life. She sent birthday gifts for me, and my son.

You can save yourself and your babies, but beyond that—everything feels uncertain.With this love, she changed me. I believed in her, and she told everyone I was a writer. Even when I wasn’t.

My husband and kids brought her flowers and candy arrangements when we reached San Antonio. When we got to her room, she looked worn down but happy, 40 pounds lighter than I had seen her before. She had lost hair, but her skin was still bright, shining from the inside out. She told me she would get out of the hospital tomorrow morning, and I think she had convinced or begged or demanded the doctors let her out so I wouldn’t have to be with her in the hospital for longer than a day. Her husband thought that, too. She never liked me seeing her sick.

The next day she was wheeled into her home. She saw her house filled with flowers and a banner that said, “YOU ARE MAGICAL” in her living room. She didn’t want to stay home, so I took her to get her nails done. She insisted on going to the aquarium next. So, I took her and we even had something called “a sloth encounter.” I watched her stand up from her wheelchair and walk slowly toward the sloth, then feed it. She insisted I do it, and I was completely repulsed.

“You have to,” she said. “Imagine if you missed this opportunity.”

We stayed a few days, and she ate less each day. I brought her food from places she liked, but all I saw her eat was a pizza crust. That was all I saw her eat in three days. I look back and can’t understand how I thought she would recover, or that things would be okay.

And still, there was no word about Shawnee. I slowly started to sink into myself and then we packed to go back home. We left in the afternoon and told Rhonda we’d be back soon. Thirty days later she passed away from an infection.

Money doesn’t bring people back, but I thought it could keep some people here.

When I offered a reward to anyone who brought information about Shawnee’s disappearance, I felt good. I imagined someone would want the money. I imagined that the problem with Indian women going missing was that people think we have no value, but even when you put value on us—they don’t care. We may not be invisible anymore, but they still want us to disappear.

Shawnee was a mother. She was without a home. People might say homeless, but the word feels too definitive for her as a person, too limiting. She was a woman living in Hope, British Columbia, without a home. She was poor, like I used to be, before the book. She was a lot of girls I know. Her leaving the world felt definitive, and final. It felt like a horror story actualized—breathing next to you at night.

When she was found in the Delta River, her brother said she would have had to walk 200 kilometers in the wilderness to end up in that river. He couldn’t understand how the police didn’t find it suspicious. But that’s how the police labeled her death: not suspicious.

It hurts to tell this story to you.

I’ve been on highways, on busses, in strangers’ homes, and I’ve begged for help before. That felt final, too, but for me there was always one small act, or one internal voice that saved me. I kept running away, into myself—into success.

I tell my students, people I read to, Native women, “This world and these rooms might not have been designed for you, but you have to walk into the room and take the knowledge you need. Walk out with it. Don’t take anything else home.”

I knew I could take what I wanted from the world. I knew I couldn’t be stopped.

But nobody told me how much it would hurt. You can save yourself and your babies, but beyond that—everything feels uncertain. Like a shoe about to drop. All I can do is remember what I received in life beyond the money.

Things like my mother standing by the river, telling me I had power. She put down tobacco for me, she prayed things would be better for me than things were for her. Those prayers might be what saved me.

But money can’t bring her back, my mother who ran her hand through her hair like she was pulling it out. She died ill. She died tired. She worked to the point she neglected herself, and me—and still, we didn’t have much food in the house.

When I got the call that Rhonda died, I was at my mother-in-law’s house. We drove home. I couldn’t stop crying. When we got to my door, I checked the mail. Letters from my mother to my mother’s best friend, Geri, were in the box. Geri had sent them, apropos of nothing. The letters were dated 1995, and later. They talked about sisterhood and love, and fighting for better things; about the need for money, but the resentment of it.

I don’t look for reasons in the bad. Mom said colonization was like an abuser in denial. I started to think about how a lot of things in my past and future are not in my hands. Mom told Geri that she was worried about rent, and in the next letter, a relative put some cash in her hand and fixed the issue. This, she said, was life and community. I think about her teachings.

Some people’s lots are bad, because of colonization, injustice, bureaucracy, because of hatred—because there’s nothing more dangerous to the colonizers than us with cash in our hands, with food, with rent money, with education, with knowledge. It’s why, when the royalties came, I gave my brother money for rent, before I left for San Antonio. With the second royalty check, I got my friend out of eviction. I told her she could do anything.

I don’t look for reasons in the bad; I look for the good shoe, that comes every time, after every death, after every bad shoe, every sadness and hunger. That’s what I have now, that—and royalties.

____________________________

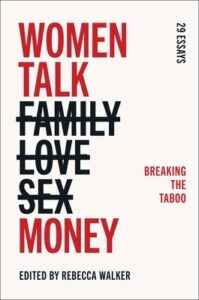

Excerpted from Women Talk Money: Breaking the Taboo edited by Rebecca Walker. © 2022 Rebecca Walker. Reprinted with permission of Simon & Schuster.