Telling Their Own Stories: On Black Women's Leadership Memoirs

"This is the Story of a Colored Woman Living in a White World"

Mary Church Terrell began her narrative with a declaration: “This is the story of a colored woman living in a white world. It cannot possibly be like a story written by a white woman. A white woman has only one handicap to overcome—that of sex. I have two—both sex and race. I belong to the only group in this country, which has two such huge obstacles to surmount. Colored men have only one—that of race.”

The clear framing of her life in terms of dual and interlocking operations of racism and sexism is very important to mapping the genealogical development of intersectional thought within Black feminism. Although a range of both academic and political thinkers would emerge in the latter quarter of the 20th century to articulate the political implications of Black women’s interlocking and simultaneous oppressions, Terrell very clearly articulates what is at stake by 1940. What Frances Beale will call “double jeopardy” in 1970, Terrell called a “double-handicap” 30 years earlier.

Though a cursory nod is always granted to Terrell in conversations on Black feminism, her assertion of the ways that race and gender politics work to make the stories and experiences of Black women invisible is one of the earliest articulations of the political stakes of intersectionality. Not only did she want to distinguish her narrative from that of white women, but she also wanted “to show what a colored woman can achieve in spite of the difficulties by which race prejudice blocks her path.” Race women experienced sexism differently from white women, and racism differently from Black men. By framing her life narrative in intersectional identity terms, she made the case that womanhood in particular is a significant category of experience in shaping Black female race leaders. Through her narration of the personal experiences of marriage and motherhood, and her more public experiences of intellectual and political development, she demonstrates the manner in which her social location as a Black woman uniquely shaped each of these experiences.

Terrell’s autobiography should be understood within the context of her broader political framework of “proper, dignified agitation.” For instance, invoking language identical to that found in the epigraph to this chapter, she writes, “I have not tried to arouse the sympathy of my readers by tearing passion to tatters, so as to show how wretched I have been.” By reminding her audience that she refused to use unnecessarily incendiary and divisive speech, she invoked her own notion of dignified agitation: “I do not want to wage a holy war or any other kind of war upon a group which is strong and powerful enough to circumscribe my activities and prevent me from entering fields in which I should like to work. . . . No colored woman in her right mind who has had as many genuine friends in the dominant race as I have had . . . could be bitter toward the whole group.”

Becoming conciliatory and racially respectable in tone, Terrell undoubtedly wanted to win the trust and confidence of her audience, whom she clearly understood to be multiracial. She also returns to this sentiment at the end of the book:

In writing the story of my life I might have related many more incidents than I have, showing my discouragement and despair at the obstacles and limitations placed upon me because I am a colored woman. Several times I have been desperate and wondered which way I should turn. I have purposely refrained from entering too deeply into particulars and emphasizing this phase of my life. I have given the bitter with the sweet, the sweet predominating, I think.

In speaking of what is not spoken about in her narrative, of her inability “to tell the whole truth,” Terrell points us to an absence that is at the heart of this project. Carla Peterson, drawing on the work of postcolonial theorists, argues that these kinds of elisions in African American women’s literature signal a challenge to the boundaries of dominant discourse by “inscribing both presence and absence in [these] texts.” Terrell, then, resists narrating a story of discouragement, despair, and desperation but fully acknowledges the ways that her encounters with racism and sexism have produced this full range of emotion. Instead, she focuses on a more public story of triumph, one that is perhaps more politically palatable. In this regard, the public nature of her story fits with Williams’s conception of organized anxiety as the kind of animating emotional ethos of Black public life. Terrell does not deny the range of anxiety-producing experiences, but she frames these experiences in terms of how they influence and inform her career as an organizer and thought leader.

Black women’s leadership memoirs have been a critical site for the articulation of their intellectual and political goals. Less concerned with the interiority of their subjects, this genre afforded Black women, particularly those who emerged during the 1890s, the opportunity to theorize about race and gender politics in ways that their lack of access to producing more formal academic texts did not. In fact, the leadership memoir is the most common kind of book-length work produced by early Black women public intellectuals, a fact that stands in marked distinction to the range of texts produced by public Black men. For Black women “the personal narrative became a historical site on which aesthetics, self-confirmation of humanity, citizenship, and the significance of racial politics shaped African American literary expression.” But these narratives also served as a site of theorizing about racial and gender identity, in addition to providing space in which race women could set forth their public agenda for racial advancement, citizenship, the defense of Black humanity and personhood, and a historical knowledge of Black achievement.

Of this theoretical impulse undertaken in Black autobiography, Kenneth Mostern avers that “nearly all African American political leaders (regardless of politics; self-designated or appointed by one’s community) have chosen to write personal stories as a means of theorizing their political positions.”41 Terrell understood her position as “a colored woman in a white world” to be a politicized position, which made her life of activism unique. Thus, her autobiography provided space for her to articulate how her race and gender identity had shaped her life and her politics. Though intersectional accounts of identity are the current order of the day in contemporary feminist scholarship, Terrell’s explicit intersectional framing of her life story, her invocation of a Black woman’s standpoint through which to tell her narrative, is the first of its kind.

__________________________________

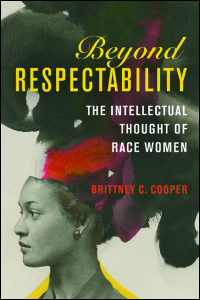

From Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Used with permission of University of Illinois Press. Copyright © 2017 by Brittney C. Cooper.

Brittney C. Cooper

Brittney C. Cooper is an assistant professor of women's and gender studies at Rutgers University.