Telling the Story of Zimbabwe's Subversive Creatives

The Brooklyn Public Library Showcases Artists Who Defied Authoritarian Rule

Next year will mark the 40th anniversary of Zimbabwean independence, which came after nine decades of colonial rule, 15 years of a white segregationist government, and 13 years of war. Through it all, the country’s writers never stopped. But in order to continue working, they had to get creative.

The first book to be published in the Shona language, Solomon M. Mutswairo’s Feso, came in 1956. That date is not the starting point for the exhibition Beautiful Words Are Subversive, on view at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Branch through January 5, 2020. Black Chalk & Co., who organized the exhibition, is interested in what came before then (texts published overseas during colonial rule; black writers writing in the colonizer’s language), what could have been (clandestine, anti-state writing behind closed doors) and what exists in the present day, at a time when the country’s once-robust publishing industry is government-censored, Feso is banned, and the indigenous literary archive is underground.

Black Chalk & Co. is the partnership of two Zimbabwean creatives: Tinashe Mushakavanhu, a writer and editor, and Nontsikelelo Mutiti, a visual artist and educator. The Brooklyn show, this exhibition’s third iteration, is spread throughout the Prospect Heights library. Glass display cases at the main entrance hold Mushakavanhu and Mutiti’s artwork, which straddle continents and decades. On display are T-shirts that the skaters outside Grand Army Plaza could be wearing, printed with selects from the archive: a faded photo of partiers from Zimbabwe’s independence celebrations in 1980; a newspaper clipping announcing Bob Marley’s appearance at the celebrations, uniting Brooklyn’s Caribbean diaspora to the continent; and a reproduction of author and poet Dambudzo Marechera’s branded merch tee from The Voice, Britain’s weekly black newspaper.

There are also the “lost books,” which fit in the genre of biomythography, Audre Lorde’s concept of combining history, biography and myth.

“We have a set of books that we have just published ourselves that have never been published before,” Mushakavanhu said. “Because when you go into the archives, there always there’s always a list of books that [have] so much literature around them, but the actual text is missing.” It is their physical existence that matters, these little pink books that we see but cannot read.

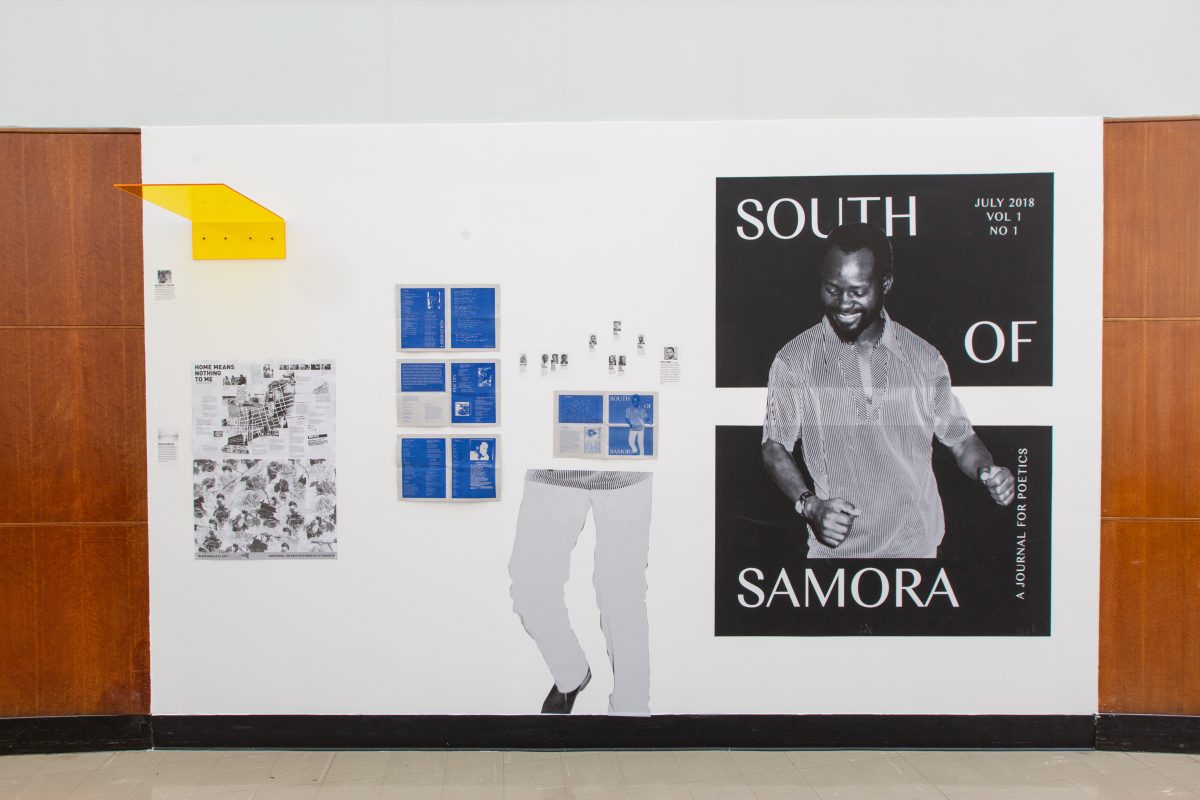

Viewers of the exhibition can read, along the library’s second floor balcony, issues of South of Samora, a zine made by Black Chalk & Co.

“Because we were seeing so little publishing, publishing dwindling in our nation, we thought, ‘Oh, can we participate?’” Mutiti said. “Zimbabwe has no history of literary magazines, and we’re constantly thinking how, through our work, we can also build platforms for creative production, critical thinking.”

“Archives are personal. Everyone who creates a repository does it because of what they care about.”

Starting in 2018, Black Chalk & Co. printed the zines in Grahamstown, South Africa and Richmond, Virginia, where Mutiti teaches graphic design. On light newsprint and in hot pink font are excerpts of celebrated work from established national writers as well as emerging poets in Africa and in the diaspora. It’s a colorful joy to flip through. Because, Mutiti wonders, how else do you get someone who only associates Zimbabwe with former president Robert Mugabe, who never before sought out authors like Doris Lessing or Charles Mungoshi, to pick it up? “If it’s not already important to people, how do you make it irresistible?” she asked.

Beyond getting these stories to individual people, how do you demand increased visibility within the structures that have long buried them? Mushakavanhu and Mutiti are interested in the available ephemera as much as they are looking at the gaps in our bookshelves. The American publishing, archiving and education hierarchies, which house much of the African literature in the world today, are part of the conversation.

Black Chalk & Co. mapped the universities where Zimbabwe-related projects have taken place, “simulating what a PhD thesis [on the country’s culture] looks like.” They collected over 200 dissertations, a process that Mutiti said was also about situating their own work within an academic, diasporic context, “acknowledging [their] place within the voices of other people that have left home and been concerned about home.”

Accumulating and gathering are activities at the core of Beautiful Words Are Subversive. The colonizer’s archival methodology is employed and at the same time reimagined as Black Chalk asks: Who is allowed to tell the story of a country?

“Archives are personal. Everyone who creates a repository does it because of what they care about,” Mutiti said. “What’s processed in the archive, how things are categorized in the archive… how fast those things happen, how people are told that those things exist so more scholarship can happen… It’s all because of the value system of the people that organize thought.”

Photo by Gregg Richards, courtesy of Brooklyn Public Library

Photo by Gregg Richards, courtesy of Brooklyn Public Library

The dissertations, the zine and Beautiful Words Are Subversive grew from Black Chalk’s first project, Reading Zimbabwe, also a personal archive. The online bibliography, with its references to thousands of books about Zimbabwe, takes a clean visual approach. The interface is designed for users to scroll through book covers classified into categories that Black Chalk & Co. created: Literature & Society, Mugabe, Urban History, War Veterans, and others. Clicking on Yvonne Vera’s 2008 biography, written by her mother, Ericah Gwetai, you get a short synopsis, an excerpt of a critic’s review, a couple sentences on Gwetai, and links to related entries.

“When you go to our website, there’s no commentary [on these books],” Mushakavanhu said. “And that was a very deliberate choice because there’s so much we can say about even absences… about history, about censorship, about the politics of publishing, about power. For us, [this is not a] limitation. I think it forces us to rethink our language, to create new languages, to experiment.”

On November 21, Black Chalk & Co. will celebrate their new book, Some Writers Can Give You Two Heartbeats, with a film screening in the exquisite corpse style, in the library’s Dweck Center. African artists will respond to prompts about Zimbabwean literature and its archive, creating a video collage. Black Chalk & Co. assert that “literature” can be multimedia and open to interpretation, “formed and deformed by necessity.”

On November 3, the library hosted a performance of Tanyaradzwa A. Tawengwa’s choral drama, Dawn of the Rooster, as part of the exhibition. The composer, on stage with her mother, sister and collaborators, sang stories of the Second Chimurenga, the 1965-1980 revolution that ended white-minority colonial rule in Rhodesia. Tawenga got everyone standing, singing “kumberi” (“forward”) and clapping to the liberation tune.

Beautiful Words Are Subversive, in its temporary Brooklyn home, is both for Africans, to enjoy and to see themselves reflected in the library institution, and for people who couldn’t place Zimbabwe on a map. “We are about conversation, not confrontation,” Mushakavanhu said. “Everything we do is a provocation.”

Greta Rainbow

Greta Rainbow is an artist, writer and radio producer living in New York.