Telling the Real Story Behind the AIDS Panic in a Small Florida Town

Steven Reigns on the Case of Dentist David Acer

As an eighth grader in 1991, my afterschool routine involved saltine crackers and tabloid TV—then at its lurid peak (or nadir, depending on your viewpoint). I found myself drawn to gay subject matter: any tale of a top BMW salesman who moonlighted as a stripper, or the rise and fall of a closeted teen heartthrob, or the career in pictures of a male supermodel. I also saw stories on A Current Affair and Inside Edition about a young woman who claimed she was a virgin, but despite that, now had AIDS. There was also a grandmother, similarly afflicted. Both women blamed their dentist for infecting them. These segments didn’t especially grab me at the time, but I did remember them.

In 1991, AIDS was a far-off threat to other people. By 2000, I faced it head-on. I had a best friend and an ex-lover die of AIDS-related illnesses. I was wildly sexually promiscuous and terrified of getting HIV myself. Rather than run from the threat, I sought safety in the center of the storm. I began work as an HIV educator and test counselor in Florida, personally testing more than 9,000 people before I left the field in 2013. One of them was an anxious young woman who came to see me after a dental procedure, terrified she might have contracted HIV. She tested negative, but I made the connection between her panic and the other young woman I saw on afterschool TV.

By then, I knew that such a transmission route was unlikely, so I investigated further. I discovered the name of the dentist, Dr. David Johnson Acer, and the women who accused him of giving them HIV while under his dental care: Kimberly Ann Bergalis, the alleged virgin, and a grandmother, Barbara Webb. Over the years, Bergalis had become something of an icon, featured in media articles and photographs, artwork, a play, and books. I found a statue of her, a beach bearing her name, a People magazine cover story. I could find little online about David Acer’s personal life.

There was no humanity or generosity in the media treatment of the now-dead dentist. Article after article repeated what had been said before.

Everything written about the situation appeared to be riddled with homophobia and unsubstantiated fears about AIDS and HIV. There was no humanity or generosity in the media treatment of the now-dead dentist. Article after article repeated what had been said before. I searched for a more balanced perspective—perhaps a journalist who wanted to tell the other side of the story, or anyone who challenged the prevailing, prejudice-driven, hysterical narrative with reason and facts—and there was none. Try as I might, I couldn’t find what seemed like an objective account of what really happened in Acer’s dental office in the mid-1980s or about Acer himself.

I became obsessed with finding that truth. In 2012, I ran an ad in a local paper with a photo of David and said I was interested in talking with people who knew him. I was curious if, years after the furor, new stories might emerge.

My phone rang off the hook. Some callers had never met Acer, but nonetheless had an opinion or wanted to castigate me for my curiosity. Some callers had known him, coworkers, friends, patients, and eventually I found my way to one of his sexual partners. I talked to countless individuals on the phone before booking another trip to Florida to meet them face to face. The ad blipped the radar of a local reporter, who questioned my motives. Why the interest in Acer, so many years later?

At that point I wasn’t ready to talk or share any of my research. The journalist published a story anyway, about my investigation. I remember picking up a copy at the gas station, somewhat bemused that my activities had made the front page of the Sunday edition above the fold and accompanied by a sad emaciated photo of Kimberly. The media still deemed her story, the blameless virgin, to be at the center of the narrative; the gay man still hidden in the shadows, his life and version of events still unheard.

After this story ran, every single one of my interviewees canceled. They “didn’t want to get involved.” One gay man, who eventually did talk with me, explained his friends warned him off. Much of the shame and stigma of being or being associated with someone gay and/or positive in that small community hadn’t changed since the height of the AIDS moral panic.

As any closeted gay man alive during that time will tell you, if you were a professional living in a small city, you had to sneak around to the next town over to survive.

The trip to Florida wasn’t a waste of time, however, despite the abruptly canceled interviews. During the day, I explored dusty archives in courthouses and libraries. When they closed, I hung out in places where I might meet locals who had known Acer and his accusers. I sat in bars and talked with anyone who looked old enough to remember 1991. I purposefully stood in a long line at a barbershop so I could strike up conversations with the older men waiting. At one point I followed suggestions of employees at retail shops who suggested potential contacts. It was incredibly helpful as I reached people who hadn’t seen my original ad or ignored it, figuring I was only interested in salacious gossip.

While pounding the pavement like this, I found an old friend of Acer’s. She told me of how he took her and the underprivileged kids she worked with on daytrips with his boat, how he did her dental work at a discount, and mostly about her deceased best friend who was once David’s boyfriend. It was another glimpse into who the shadowy dentist had been.

Acer’s parents moved into his home to care for him and stayed there after he died to handle his affairs. A friend of theirs told me how he had dinner with them one evening and heard a stream of harassing messages as they came in on the answering machine. David’s mom once showed him the pile of disparaging letters she received that week. Acer’s family had chosen dignified silence throughout the years; because of this, there was not any pushback against the narrative spun by the high-powered attorneys acting for Bergalis, Webb, and a series of other alleged victims who came forward with similar claims. He didn’t have an advocate.

I felt as though I could step into that role as a member of the gay community who lived for a decade in Florida. I wanted to challenge the true-crime-style retelling of Acer’s story in popular media, which had presented him as a serial killer who had led a double life and traveled—by night—between cities to find sexual partners, ultimately bringing the plague home to his blameless patients.

As any closeted gay man alive during that time will tell you, if you were a professional living in a small city, you had to sneak around to the next town over to survive, to meet other gay men, to find people far outside your social circle who would understand and keep your secrets, as you would keep theirs. When Acer was accused, he had no out gay friends to stand by him—any supporters would have been destroyed in the court of public opinion. Those who knew his truth stayed hidden, silent, afraid. One of his employees told me news vans besieged her house for weeks, hoping for tidbits.

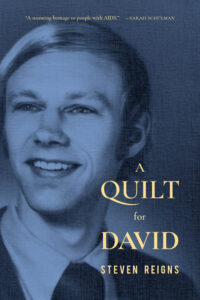

A Quilt For David is the result of numerous trips to Florida, where I worked my way through court documents, library archives, and personal interviews. I processed this research by writing poetry and short prose pieces about my response to the material I uncovered. Documentary poetry is a new and thrilling form for me it’s a way of excavating these semi-forgotten events to address where we were as a culture then, and how we betrayed the truth of David Acer, and so many others who suffered with AIDS and HIV.

There’s no poetic license or whimsical fantasy in A Quilt For David. I didn’t want to add to the reams of ugly misinformation and lies that have, until now, formed the lasting record of Acer’s life. Every detail in the book comes from my investigation. I will be donating my extensive research papers to The One Archives, in the hope that I have laid the groundwork for the future, so that more light can be shone on what really happened in Acer’s dental office, and how outside factors helped focus so much negative attention on a dead gay man.

___________________________________________________

Steven Reigns’s A Quilt For David is available now from City Lights Booksellers & Publishers.

Steven Reigns

Steven Reigns, Los Angeles poet and educator, was appointed the first Poet Laureate of West Hollywood. He has two previous collections, Inheritance and Your Dead Body is My Welcome Mat, and over a dozen chapbooks. Reigns edited My Life is Poetry, showcasing his students' work from the first-ever autobiographical poetry workshop for LGBTQ seniors. Reigns has lectured and taught writing workshops around the country to LGBTQ youth and people living with HIV. He worked for a decade as an HIV test counselor in Florida and Los Angeles. Currently he is touring The Gay Rub, an exhibition of rubbings from LGBTQ landmarks around the world, and has a private practice as a psychotherapist. He lives in West Hollywood, CA.