Teenagers at War: On Fighting the British in New York, 1776

Jack Kelly Chronicles the Experience of a Revolutionary Soldier During America’s Fight For Independence

By September 1776, Thomas Paine had done more than any other individual to convince Americans to break their ties with England and to declare themselves independent. He well understood that dispensing with the centuries-long tradition of monarchical rule was a dangerous and daunting endeavor. But even he did not fully grasp the sacrifice that would be required or the depth of the crisis that now loomed over his adopted homeland.

One who had heeded his words was a young Connecticut lad named Joseph Martin. He may have read Paine’s delicious phrases in a pamphlet, or he may have heard them repeated in the town square. We have it in our power to begin the world over again. Yes! It was the shining hope of the young. Remake the world. The words had stirred Martin, sounding a chord in his heart like an organ in church.

So, on a hot July 6 in the year 1776, four months shy of turning sixteen, Joseph had said to a young friend, “If you enlist I will.” To himself he whispered, “I may as well go through with the business now as not.” Independence in the air, he went through with it. He signed up for six months to “try out sogerin’.” He had become a musketman with Peck’s Third Company of Douglas’s Fifth Battalion of Wadsworth’s brigade of Connecticut new levy militia. He had joined a revolution.

Folks would talk about it like they did about Julius Caesar and General Wolfe. He and his fellows were going to shine in history.

When he had first put on the uniform, Martin had felt his soul expanding. He sensed his frail body growing larger, tougher. As he marched in step with his fellow soldiers, he gloried in a greater sense of life. He and the men of his regiment were a muscular creature, more powerful, more forceful, far grander than any individual man. He was part of an army.

His regiment had ridden a sloop down Long Island Sound through Hell Gate and along the dirty river to the wharf at New York City. At the time, the entire city extended barely more than a mile north of its southern tip at the Battery. Martin and his fellows had paraded proudly on Broad Street. They had joined the mass of armed men commanded by George Washington, men who would fend off the onslaught of the king’s forces.

*

That was then. Now, in mid-September, the sluggish Sunday morning found Martin and his regiment stretched out along Kip’s Bay, a cove two and a half miles north of New York City.

Now he lay in a ditch behind heaped dirt along the bank of the East River. He had been on duty all night, his eyes peering into blackness till they ached. He had watched the starlight flash on the black water. Now the heavy air and an empty fatigue pressed against him. The smell made him think of a freshly dug grave. He wiped his mouth with his sleeve, swatted at the age-old insects pestering his face.

He allowed a deep pity for himself to suffuse his breast. He was hungry and morning had brought no food. The predictable rhythms of his childhood had gone awry. He had to go where he was ordered, but he sensed that the officers did not know what they were doing. They were pulling strings to make him jerk this way and that.

The unseasonable heat made it hard to concentrate. At dawn, four British warships had heaved into sight. They stopped directly opposite the American troops. Their clanking anchors dropped with mighty splashes. The chains rattled out. The rising sun became tangled in their rigging.

Martin and his fellows stared at these looming vessels. They were close enough to let the recruits exchange banter with the tars, who were busy attaching spring lines to the cables so that they could revolve the ships with capstans and point their gaping cannon at the shore. Close enough for the Americans to read Phoenix on the stern of the largest. Blessed Jesus, forty-four guns on two decks run out for action.

Joseph clung to the notion that he and his mates were veterans, already tested by war. Just two weeks earlier, during the swelter of August, the regiment had gone aboard a ferry at the foot of Maiden Lane to cross the river to Brooklyn. Cannon fire, musketry, and smoke announced that a fierce struggle was raging there. Before leaving, the soldiers had shouted together, three cheers. The roar from their throats had been answered by the shouts of the people on the waterfront, who were not going over.

Too bad for them, Martin had thought with secret scorn. Events were afoot—he was determined to feel the pulse of history. He was about to join in a battle, just like you read about in the books. Folks would talk about it like they did about Julius Caesar and General Wolfe. He and his fellows were going to shine in history.

As the regiment swayed toward the landing opposite, he had turned away from his scareful imagining and swore, “I will endeavor to do my duty as well as I am able and leave the event with Providence.” On landing, he saw wounded, blood-crusted men, men limping and carried along. “The sight of these a little daunted me,” he remembered, “and made me think of home.”

He had tried to fight off the crowd of memories that appeared to his mind as if he were looking into the wrong end of a spyglass. Milford, his hometown sixty-odd miles up the Connecticut coast, was as far away as the moon. The arduous hours of plowing there now seemed play; the soft remonstrances of his grandfather, love sounds. The morning meadows of the home fields, dancing with bees and midges, were a distant paradise.

During the day of the fight at Brooklyn, he had watched the Maryland and Delaware boys sprint into the Gowanus millpond. The regulars fired at them with a booming 12-pounder that made the American boys lift their knees like old hags, trip and founder as tentacles of water dragged them under. The roar was something.

One man arched his back and fell. Oh, God! Another gasped and splashed, the water choking him. Them that got across emerged rat-like, coated with sopping sludge. After the tide went out, Joseph joined with others to wade into the mud and pull the bleach-white, slime-smeared corpses to land. Others came running from up the lines, telling tales of horror, of friends’ bellies ripped by Hessian bayonets, of redcoats surging at them from every direction.

His regiment marched here and there and fought a band of scarlet-clad foot soldiers near a cornfield. Their muskets made an angry stamping sound. Confusion snarled Joseph’s mind. A heavy burst of rain tore up the sky and left him and his fellows soaked. With night came whispered orders to march back to the ferry. They moved in perfect silence, not even a cough allowed. They boarded boats and were glad to make it across the river again, glad to be alive.

Now, in the heat of September, the war seemed like a dream. Now this immediate threat, the hulking ships, laughing sailors, yawning black cannon mouths, gave the lie to the notion that they were veterans. His blood thinned with the expectation of what was to come. War, Martin saw, had many faces.

Around them, the pastoral countryside lay stretched in neat farm fields and wooded lots. It offered a false reassurance. The inward arc in the riverbank ascended to form a glade, trees standing sentinels at its upper edge. Two streams skipped merrily down the hill and merged before adding their glassy waters to the bay (now erased by landfill, Kip’s Bay stretched from today’s 31st Street to 38th Street along Manhattan’s east side).

The angry red globe of sun climbed over the opposite shore. The infantrymen around him peeped painfully over the heap of dirt that substituted for a breastwork.

He wanted the bombardment to end, wanted quiet to return, wanted not to be here, wanted to be home, wanted to awake from the dream.

“Here they come! Here they come!” Someone was shouting. Dozens of barges were gliding out from a creek on the far side. Then more and more yet, scores of ’em, each propelled by sixteen strong rowers, each holding sixty tall men standing in ranks, each man with a shining musket on his shoulder and a bayonet pricking the sky.

Young Joseph knew them by their uniforms. The fast-running light infantrymen were lining up opposite his own position at the north edge of the bay—red jackets, small caps. The barges filled with grenadiers in towering bearskin headdresses were gathering just downstream. The most distant were the Hessians, green- and blue-jacketed killers. The barges were slipping through the gaps between the warships and bobbing on the choppy water. The rowers held them motionless against the current. After his long night’s watch, Martin’s mind was fogged by weariness.

He could not take the waiting. He crept away from the river and stepped through the morning quiet to explore the large shed just behind where his regiment lay. He hoped without hope to find a bit of bread there, anything to ease his angry innards. He had not tasted a morsel since yesterday morning. Thoughts of pie and pork and ripe apples made him even more famished.

No luck. The creaky, empty building must have been a warehouse for the farm up the hill, a counting house where they recorded the shipments leaving from the small wharf. Flies danced in the heat; shafts of sun illuminated the dusty air. The high room stank of piss and the droppings of doves.

He sat on a stool and leafed through the papers strewn about, receipts and invoices, notifications and ledgers. They were the registers of a prosperous trade in milk and honey, butter and eggs to the New York markets. He liked to read, liked the feel of paper, the elegant flow of the script. He traced a capital T with his finger and remembered his grandmother holding his hand with the quill pen, making his first letters. The little curls were important, they—

Without warning, the world exploded. The still, humid air roared to life, punched him off the stool, slammed his tailbone against the floor. The noise mounted until it was shattering the air into fragments that pommeled his head, his gut, his arms and shaky knees. “I thought my head would go with the sound,” Martin remembered later.

He was not the only one who was impressed by the barrage. Ambrose Serle, secretary to the British commander General William Howe, wrote that “so terrible and so incessant a roar of guns few even in the army and navy had ever heard before.”

Martin felt himself flying. With a thump to his chest, he was back in the ditch, gripping his musket, pressing himself into the wormy earth. His brain swam, his sweat flashed to ice, as if he were in a fever. The air stank of roasting sulfur. Joseph inhaled a thick fecal odor he hoped was not his own. He later remembered that he “lay as still as I possibly could and began to consider which part of my carcass was to go first.”

The blasts from the looming ships yanked the breath from his lungs. The roar banged against the limits of sound, numbing the soldiers’ ears. The noise erupted in violent staccato, again and again and again, coming too fast, shoving the young recruits farther into the ground, their fingers clawing the clay, their instinct to burrow. Emotions with no names gripped Joseph Martin, then vanished in a second. He tried to stop his mind from careening.

Round shot roared overhead, plowing the dirt behind them. Grape and canister screamed past with the whistling squeaks of demented birds. To breathe the pall of smoke was like inhaling vinegar.

The noise punctured his treasured illusion of the regiment as a muscular animal. Each man suddenly shrank back inside himself. Terror ignited a deep and chilling loneliness in Joseph’s heart.

He wanted the bombardment to end, wanted quiet to return, wanted not to be here, wanted to be home, wanted to awake from the dream. But the catastrophe continued until it seemed as if it would dismantle the earth. Was nobody in charge of the world no more?

__________________________________

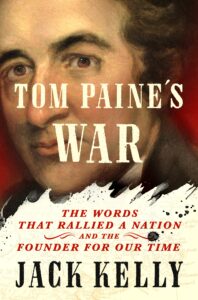

Excerpted from Tom Paine’s War: The Words That Rallied a Nation and the Founder for Our Time by Jack Kelly. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Jack Kelly

Jack Kelly is an award-winning author and historian. His books include Band of Giants, which received the DAR History Medal, and God Save Benedict Arnold, a Finalist for the New England Book Awards. He has published five novels, and is a New York Foundation for the Arts fellow in Nonfiction Literature. Kelly has appeared on The History Channel, National Public Radio, and C-Span. He lives in New York's Hudson Valley.