Teaching in a Red County, After Trump

Melissa Febos Asks, "What is More Powerful Than Inspired Youth?"

The day before the 2016 presidential election, I taught a literature class to 25 students, few of them English majors. I work in a red county in New Jersey, at a private university where Trump was elected by a small margin in our undergraduate student body’s straw poll. Our student population is more than 60 percent white, with a high number of first-generation college students. Despite it being an hour’s drive away, many of them have never been to Manhattan. Most of them have never left the country, and some not even the county—for lack of motivation rather than resources. I often struggle to relate to them academically; I was an intellectually ambitious, highly politicized college student who idealized radical feminist thinkers and was so motivated to learn that I wrote a senior thesis twice as long as was expected.

I suspect that my students are a pretty ordinary sample of their generation. They are also, on the whole, kind, good-natured, and teachable. Some are incredibly talented and perceptive. In my four years of teaching them, I have calibrated my curriculum to reach them where they are, and a lot of the time it does. This requires a kind of pedagogic creativity that isn’t taught in graduate school, and reaching them is rewarding in ways that I couldn’t have anticipated.

I teach them about feminism without ever uttering the word feminism, because I know how instantly the word will alienate my students. I teach intersectionality without ever defining it. I fill my syllabi with women and writers of color and don’t announce it. My students don’t seem to notice. But they read the books. And when I see that flicker of awakening in their faces as they discuss James Baldwin or Jesmyn Ward or Joy Harjo and connect their own sympathies with people different from them, sometimes for the first time, I am grateful that I teach here and not at a school where the undergraduates are already fluent in the jargon of hegemony, diaspora, paradigm, and intersectionality.

I had planned a discussion of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. As usual, we opened class with a couple of student presentations on the text. There were five students of color in the literature class, three of them young black women. One of these gave the first presentation. A quieter student, she passed out her handout and stood at the front of the classroom. In a trembling voice, she faced the room full of her white classmates and began to explain race as a social construction. She stumbled and searched for her words. She clenched the piece of paper in her hand, with its bulleted notes. The topic of her presentation was the “ethical content” of the assigned text, and in this halting manner, but with her head held high, she discussed the “ethics” of slavery. Just after she described the way slave women had their newborn infants taken from them and sold to other plantations, she paused and stared out at the silent class. She blinked. “Just imagine,” she said. And then continued.

“I am grateful that I teach here and not at a school where the undergraduates are already fluent in the jargon of hegemony, diaspora, paradigm, and intersectionality.”

I don’t think the other students saw the tears in my eyes as she spoke, but they heard me clap for a long time after she finished. I wanted to carry her out of that classroom on my shoulders. But I knew there was no place to carry her. As I clapped, I offered a silent, fervent prayer that this election’s result would be a step toward a world in which she was safe.

*

Since childhood, my grief has had a prayerful refrain, for safety: I want to go home.

I grew up in a loving home. My mother was, and still is, a Buddhist psychotherapist and staunch feminist. My father is a Puerto Rican sea captain. They are both Democrats and are both from working-class towns in New Jersey much like the one where I teach. I spent my early life carrying signs in peaceful marches and reading while my mother attended meetings of our local National Organization for Women chapter. I also spent a lot of my childhood waiting for my father to return from sea.

“I want to go home,” I whispered alone in my bedroom at eight years old, missing him. “I want to go home,” I whispered alone in my bedroom at 12 years old after fighting with a class of fellow sixth graders about my right to love another woman. “I want to go home,” I whispered alone in my bedroom at 14 after a senior boy grabbed my breast in the high school hallway, meeting my eyes defiantly as he stared down at me. “I want to go home,” I whispered alone in my bedroom at 20 after shooting speedballs, terrified of the day that my family would find out by way of my dead body. “I want to go home,” I whispered alone in my bedroom at 36 years old on the morning that Donald Trump became our president-elect.

The home that I longed for at eight years old, at 12 and 14 and 20 and 36, was not a literal place. It was a feeling. It was a faith that I, and the people I loved, would be safe. That whatever pain we suffered would pass without killing us, or the parts of us we needed to survive, to thrive, to create love and art and social change.

No matter what our age, this kind of despair manifests in the same way: as a wish that someone will rescue us. A parent, God, a place inside ourselves where we can find refuge and reassurance that everything will be okay.

*

How could I face my students the day after the election? Ten years ago, when I began teaching, I trained myself to hide my politics. For the first five years, I even hid my tattoos. Not out of shame but out of protection. And because I wanted to do my job effectively. I wanted to teach students who had different beliefs than me to love literature, to believe in the inherent value and power of art. To understand how much of our history is archived there. I wanted to turn them into bibliophiles, champions of human rights, believers in their power as compassionate citizens. And most of the time I knew my best chance of succeeding meant hiding how desperately I wanted to succeed.

But Professor Febos did not feel like someone I could be that day. I could only be this devastated woman who wanted to go home. This queer woman sunk in terror for her country. For her loved ones. For all black and brown and immigrant and queer and trans and disabled and female people. For all the boy children, white children, and girls in her country who would learn how to be men, or white, or women—how to be Americans under Donald Trump’s administration.

And then, like so many times before, I remembered the person who had always rescued me. The person within me who had built her entire life around the ways she could best keep herself and her loved ones and her country safe. The person who had become a teacher and a writer for precisely those reasons. Because in a country whose government we do not trust, who do we need more than writers and teachers? And what is more powerful than an inspired youth? I turned off the radio. The newscasters would not make it okay. My parents would not make it okay. My students were our best hope. And I could reach them faster than anyone.

I walked into the classroom where I teach my Introduction to Creative Writing seminar and told my 15 students to take out their notebooks. I had no idea what I was going to say to them. My heart pounded as I stared at their expectant faces. Out of the 15, 12 were young white women and two were young men of color. I had no idea their politics, though I would wager at least a couple of them voted for Trump. I had no desire to alienate any of them. As they dug into their backpacks and produced their pens, I stared at them. I scoured my insides for some trust that underneath whatever differences, we all harbored an earnest desire for the safety and freedom of other humans. To my relief, I found it, a warm ember in my gut that seemed to glow when I touched it.

I told my students to describe a person opposite them in the most obvious ways: race, religion, sexual orientation, and country of origin. When their pens slowed, I asked them to describe the country they wish for that person. After a few more minutes, I asked them to think of a child they loved—their own, a niece or nephew, an infant version of themselves. I asked them to describe the country in which they wished that child to come of age.

I watched them as they wrote—their smooth foreheads crimped with concentration, their hands moving across notebook pages. When they looked up, I asked them to reconcile those visions into a single vision of a country where both of those realities could exist and both people would be free to inhabit them. They stared at me for a few beats and then began writing. Some of them paused, pens hovering over paper as they stared into space and worked out some detail in their minds. They wrote for a long time. When the scratching of pens quieted, I took a deep breath. Something had shifted in the room. We all felt it. As if there was an ember in each of them, stoked by their pens, that had glowed warm and bright enough for us all to see.

“The newscasters would not make it okay. My parents would not make it okay. My students were our best hope.”

“I want,” I said, searching for my next move. “I want you to make a list.” They laughed, first quietly and then louder, because this was how I started so many of their in-class exercises and because they needed so badly to laugh. “I want you to make a list of all the things you can do to build this home for us.” This time, many of them nodded. They understood what I was asking them to do.

The room changed that day, the way it does when the space between who my students are in public and who they are inside themselves closes a little. When they take a risk and reveal something that scares them. But that day, I revealed something, too. I try to keep my own needs out of my classroom. They need me to hold the space, and it’s harder for me to do that if I hold a personal stake. But I suspect that my students understood that I needed them to collaborate with me, to imagine something better than what the morning had promised us. And they had. My students had written about their immigrant grandparents, the people they most loved, the unspoken and spoken divisions in their homes and communities. Even those students whom I suspected voted for Trump were careful in their exercises, generous in their vision. It’s hard not to be when faced with the earnest fears of people you know.

At the end of that class, I offered an open invitation for anyone to come talk to me about the election and any reaction they might have. They came. Many said it was the first time they’d spoken aloud about their fears, the ways they silently disagreed with their families. They stumbled to name their ambivalence, the disappointment they felt after voting in their first election. “It’s bad, isn’t it?” a few of them asked in the quiet of my office. “Yes,” I said. And later that semester, after Trump’s travel ban, they came back again. “It’s bad, isn’t it?” they asked, sometimes tentatively, as if they might get in trouble for wondering. “Yes,” I said. I’d never been so forthright about my own political opinions with students at this school.

In the months that have followed, my fear has settled from the searing terror and despair of that day into something quieter but no less persistent. Inside my office, I have continued being honest with them. Their political awareness is so new—if they cannot remember a time before the Trump era, it might easily become normal without the contrast of the Obama years. And of course, in the larger scope of history, it is normal. That has always been a part of my curriculum, though it has become a part of our conversations now, too.

They have not put away their lists. One of my students came to me and told me that she had started a hard conversation with her family. It went okay. Another told me that he came out to his. It didn’t go as he’d hoped, but he isn’t sorry he did it. I am not much of an idealist. I do not believe that my students are going to turn their families. That we will survive this administration without millions of casualties. That we will survive as a species who has so abused our resources.

But I have been heartened to see that so many of my students envision honesty as part of our solution. That they have recognized the integrity of revealing themselves, even when they know others will disagree with what they think or even who they are. They have not long been forming beliefs independent from those they have inherited. It is a delicate and sometimes dangerous thing to think for yourself. Visibility is a powerful political tool. My hope is that this small knowledge, that there is enough room for everyone in a single classroom, is a belief that they can carry into the world. It will, soon enough, be theirs.

__________________________________

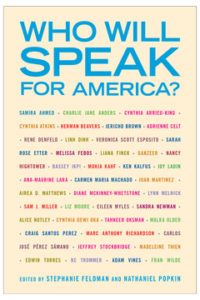

From Who Will Speak for America?, ed. Stephanie Feldman and Nathaniel Popkin. Used with permission of Temple University Press. Copyright 2018 by Melissa Febos.

Melissa Febos

Melissa Febos is the author of Whip Smart, Abandon Me, and the essay collection, Girlhood, which will be released on March 30. She welcomes recommendations for well-written, feminist, antiracist, and queer-centering mysteries. You can find her on Twitter @melissafebos and melissafebos.com.