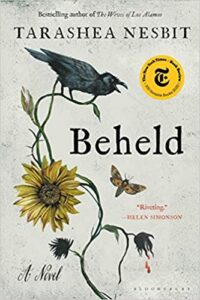

TaraShea Nesbit on Tove Jansson, Matilda, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Rapid-fire book recs from the author of Beheld

Welcome to the Book Marks Questionnaire, where we ask authors questions about the books that have shaped them.

This week, we spoke to the author of Beheld (out now in paperback), TaraShea Nesbit.

*

Book Marks: First book you remember loving?

TaraShea Nesbit: A girl lives in the particular isolation of neglected children during the years one is conscious but not yet in school. She teaches herself to read and soothes her loneliness with the characters in novels. Her parents take little notice. Eventually, a librarian gives her book recs. The girl has her wits to play tricks on her parents. When she gets to school, a teacher notices her. But even if Miss Honey hadn’t noticed her, this girl has a mind that can make pencils soar to the ceiling.

Of course, Matilda. Rereading it with my daughter I have many objections to the story, from the misogyny of the descriptions—mean women are always portrayed in visually damning ways, as one example—to the ending, in which Miss Honey adopts Matilda. I’d love to write a children’s book that features a girl lead that has the strength of her mind, scattershot support, and literature to ballast her. In the book I’d write, the parents’ neglect and harm are revealed to have origins in generational trauma. She stays in that house but saves herself.

BM: Favorite re-read?

TN: Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book and the essays in Shena McAuliffe’s Glass, Light, Electricity.

BM: Last book you read?

TN: I just finished two great books: Felicia Rose Chavez’ The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop and Yaa Gyasi’s Transcendent Kingdom.

BM: What book from the past year would you like to give a shout-out to?

TN: Daisy Hernández’ The Kissing Bug. Part investigative journalism, part memoir, and all pitch-perfect prose, Hernández tells the story of the kissing bug and the deadly disease it spreads, with a keen eye towards how diseases that are not money-makers to cure are neglected by governments and medical researchers. I also love her first book, A Cup of Water Under My Bed.

BM: What’s one book you wish you had read during your teenage years?

TN: It was not written yet, but I wish I could have read Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score.

BM: Classic book on your To Be Read pile?

TN: In keeping with the season: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

BM: What’s a book with a really great sex scene?

TN: Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies and Anton DiSclafani’s The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls.

BM: Favorite book no one has heard of?

TN: Well-known internationally, but I’ve never had a conversation with anyone in the U.S. about it: Tarjei Vesaas’ The Ice Palace.

BM: Favorite book you were assigned in high school?

TN: Twice I was assigned to choose any book that I wanted. In 6th grade, a curtain on my understanding of the world was pulled back when I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Mrs. Kuntz had it out, perhaps more as a representation of heroes for Black History Month than for the reading assignment. I say this because she hesitated when I showed it to her, said, It’s quite long. I insisted—now it was a challenge—and became newly aware of racism, bravery, boldness, and governmental involvement in oppression.

In tenth grade, Ms. Sharon Rab—who went on to found the Dayton Literary Peace Prize—taught at my mostly unexceptional public high school. I chose Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, which must have been in the front stacks of the nearby bookstore instead of the school library. Addiction and the world of an underground economy were closer to home than I was fully conscious of, so what really drew me to the book was the use of non-standard English, spelling that reflected the accents of the characters, like the opening: “The sweat wis lashing oafay Sick Boy; he wis trembling.” I read the novel aloud in parts to understand what was being said the same way I’d later delight with Chaucer in college.

BM: Book(s) you’re reading right now?

TN: When I run, I listen to female comedian memoirs and I am finishing up Ali Wong’s Dear Girls. Before bed, I read for pleasure, and I’m in the opening of Maggie Nelson’s On Freedom. When I drive into work, I listen to things I am teaching, and I’m listening to Zadie Smith’s Feel Free. For writing inspiration, I’m reading Old Growth, an anthology about trees from Orion’s archives, with a foreword by one of my favorite writers, Robin Wall Kimmerer.

BM: Favorite children’s book?

TN: For picture books: the one about the female caboose that wants off the track led by the domineering male engine and the work-work-work male bosses. By an act of chance, her coupler gets loose and she flies into the air, where she lives out the rest of her days high up in the trees with the birds, never to be bothered by the bosses or the engine again: The Caboose Who Got Loose by Bill Peet. He wrote that book right around the time he quit working for Disney.

*

TaraShea Nesbit‘s second novel, Beheld, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, a Publishers Weekly Best Fiction Book of 2020, a finalist for the 2021 Ohioana Book Award, and a 2021 Massachusetts Book Award “Must Read Book,” among other accolades. Her bestselling first novel, The Wives of Los Alamos, was a finalist for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize, a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice, and winner of two New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards. Her essays have appeared in Granta, The Guardian, LitHub, Salon, and elsewhere. She is an associate professor at Miami University.

__________________________________

TaraShea Nesbit’s Beheld is out now in paperback from Bloomsbury

*

· Previous entries in this series ·

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.