Mötley Crüe’s Nikki Sixx on Discovering Hard Rock in the Middle of Idaho

“Until Kiss and Alice Cooper came along, music had been getting softer and softer.”

Jerome, Idaho might have been small, but it had a downtown, with a JC Penney, a Western Auto, a Dairy Queen, and a couple of drugstores. My friend Alan’s grandmother worked at McCleary’s, which had a real old-fashioned soda fountain with circular stools and a half-moon crescent counter. She lived above the store, worked as a cook in the back, baking pies, and Alan and I would go hang out and drink milkshakes.

McCleary’s was a small-town drugstore straight out of the 1950s. Most of whatever you needed, they stocked: clothes, tools, magazines, and dime-store novels. They even sold records. I bought a Pink Floyd tape, Dark Side of the Moon. Alan and I listened to “Money” over and over and over again on a battery-powered tape recorder we could take out of the house. I felt the bass line to that song at a visceral level. At around the same time, I heard Deep Purple for the first time—“Smoke on the Water” came over the airwaves one day on Nona’s radio—and “Saturday in the Park” by Chicago. A few months after that, I was doing something in my room and Nona called out to me, “Hey, Frankie, that guy you like, Peter Cooper. He’s on TV.”

I knew what she meant. I didn’t have any Alice Cooper albums, but I was interested in Alice Cooper, so I ran right out, down the hall and into the room where our TV set was. We had a little TV on one of the small TV stands you can roll across the room—and there, on The Merv Griffin Show, I got my first glimpse of Gene Simmons from Kiss.

Not Alice Cooper. But Simmons was interesting too. He was dressed up, full regalia, full makeup, big boots, devil horns coming up from his shoulders, just going for full-on shock.

Merv asked him, “Are you a bat?”

“Yes,” Simmons snarled. “Actually, what I am is evil incarnate.” He leered at Merv’s audience.

“And some of those cheeks and necks look really good,” he said. Then he hissed and stuck out his very long tongue.

It was silly, way over the top, and the guest sitting right next to Simmons—an older comedian named Totie Fields—was rolling her eyes and having none of it.

“Is your mother watching today?” she asked. “Wouldn’t it be funny if under all this, he was just a nice Jewish boy?”

You can see the exchange for yourself—it’s on YouTube, and it looks as ridiculous now as it must have back then. But then the full band came out. They played “Firehouse,” and even if “Firehouse” is a rewrite of “All Right Now” by Free, it’s still a good song. You really can’t argue with that chord progression.

It was a lot to take in. I didn’t love Kiss’s look. I didn’t hate it. I never became obsessed, the way some of my other friends did. For other kids my age, Kiss became the 70s equivalent of the Power Rangers. They had Kiss lunch boxes and, later on, Kiss tattoos. I paid more attention to their songwriting than anything else, and it’s funny: Once, we were co-headlining with Kiss, and I was playing our song “Ten Seconds to Love.” I was deep in the pocket, the crowd was going wild, and suddenly I realized: “Whoa. I ripped this song off of ‘Calling Doctor Love’!”

Until Kiss and Alice Cooper came along, music had been getting softer and softer.It was the same chord progression, and we were on the same tour, and I hadn’t realized how deep their influence on me had been. But there I was, doing the same thing with Kiss that Kiss had done with Free, without even realizing it.

Until Kiss and Alice Cooper came along, music had been getting softer and softer. Jim Croce, James Taylor, Bread. I loved those lyrics and the melodies. But the harder stuff I was starting to hear got me going. I played it more and more loudly at home—and the volume started to cause problems because our house was a double-wide trailer.

Watching Tom put the two trailers together had been fascinating. He made steps and poured concrete to make a driveway. He built a little work shed and put a fence around the backyard. I had a doghouse out back for Barnaby. Nona had a garden with fruits and vegetables she liked to grow. It was a nice place—the trailers were white and Nona always made sure they were immaculate, as was our yard. But it wasn’t big. We had a kitchen, a front room, a little laundry room, and two bedrooms in the back, and the walls between those rooms were thin, so whenever I cranked my music up, Tom would start yelling: “Frankie! Turn that commie crap down!”

That’s when I realized, “If I ever get a girlfriend, I’m not going to be able to do very much with her in here.”

But when I finally did get a girlfriend, it wasn’t like that anyway. Her name was Susie. She had glasses with metal frames, like mine.

A sweet smile too. Her dad called her “Sulky Sue” teasingly, but she wasn’t sulky with me at all, maybe just a bit awkward. But, again, I was a bit shy and awkward myself—which was fine, because it seemed like we had all the time in the world to get to know one another.

We did that on walks, up to the Dairy Queen that stood on the end of Main Street and over to the ball fields just past it. It was like a Norman Rockwell painting come to life, literally Main Street, USA. Susie’s mom drove the school bus. Her dad worked at the milk-bottling plant. I’d talk to Susie about Nona and Tom, about my sister Celia and how I missed her because she lived so far away. Sometimes we held hands, maybe kissed, and the whole world suddenly felt electric, woozy, and wild, even though, looking back, it seems very wholesome—and it was.

Susie’s dad did not go to a church. “I worship God up on the mountain,” he’d say. But Susie’s mom attended the Nazarene church. Sometimes we’d go with her. There was a lot of singing of hymns, but I don’t know that those hymns made an impression. What I mostly remember is shyness, mine and Susie’s, as she sat on the bench beside me. Embarrassment at being seen in public with my “girlfriend.” But also pride, because the girl I liked seemed to like me.

Jerome and Twin Falls both lie in the same Idaho valley—Magic Valley. Once a month, all the Nazarene churches in Magic Valley went to the roller rink in Twin Falls. Susie and I went together, even though I couldn’t skate well and mostly held on to the wall. We went to the movies too, in Jerome’s one movie theater—a single-screen cinema off Main Street, next door to the bank. We held hands. Sometimes we went bowling. And there was a record we listened to all the time: a Seals and Crofts song called “Diamond Girl.” That became our summer song.

Twelve years later, when we were recording Mötley Crüe’s third album, I tried to come up with an excellent cover. We tried “The Boys Are Back in Town” by Thin Lizzy—a great song, but we couldn’t get it to work. We tried Elton John’s “Saturday Night’s Alright,” but that didn’t sound right to us either.

Then I said, “‘Diamond Girl’ by Seals and Crofts.”

Everyone else in the band said, “You’re crazy. This doesn’t even sound like a rock song!”

We rehearsed it. The other guys were right—it wasn’t going to work as a Mötley Crüe song. We covered “Smokin’ in the Boys Room” by Brownsville Station instead, and that song, from the same year as “Diamond Girl” (1973), was Mötley’s first top-forty hit. It went all the way to number three in the charts. But I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I had stuck to my guns and insisted on “Diamond Girl.”

__________________________________

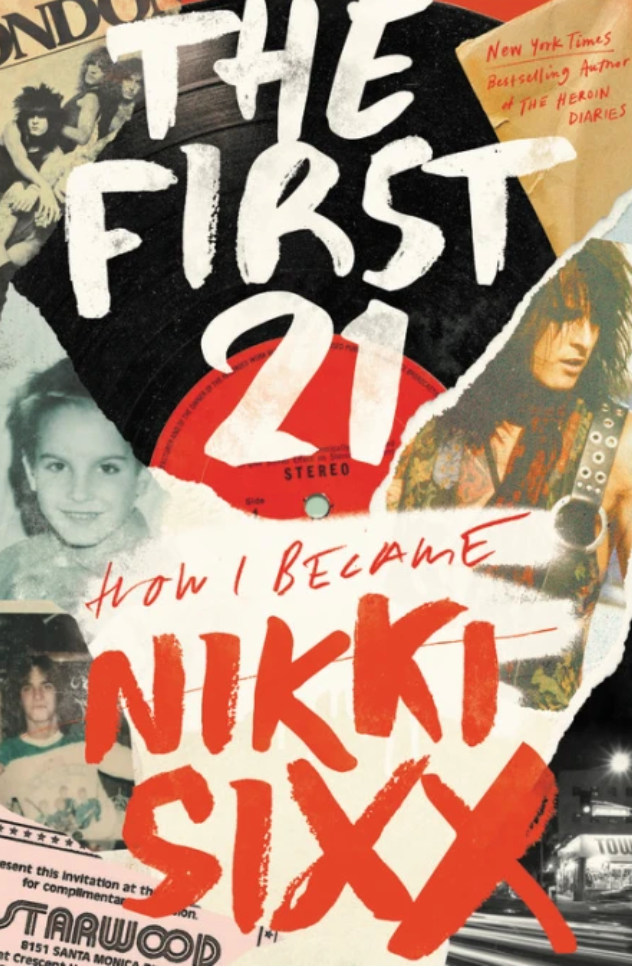

Excerpted from The First 21, by Nikki Sixx, courtesy Hachette Books. Copyright 2021, Nikki Sixx.