In my books, the spine is a simple, efficient, elegant, and functional form that can conduct and generate meaning, and as readers, we imbue meaning into materials based on the way they are presented to us. For a written narrative of any length, the spine keeps the language in order simply by connecting all of the pages in sequential order.

For publications that involve sections, the spine not only keeps the language in order, but also suggests how the sections relate to each other and the thematic arc of the publication; a spine can also connect materials that would otherwise seem completely unrelated and therefore make more specific our reading of that material. While we can read a book backwards and forwards, right and left, and up and down according to the languages that we know, the spine is a built structure that gives us a physical parameter and conceptual foundation for the experience of an artist book.

In 2021, I made a series of four interrelated artist books called Four Ways Through a Cave. Each book mimicked the experience of passing through a fictitious cave based on my own travels through some caves in the Phong Nha Karst, a cave system which spans Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos that played an instrumental role in helping to unite the Communist effort during the Vietnam War by housing part of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

These artist books were an extension of my written book O, which partly describes this experience along with other fictive, biographical, and historical components. These two projects differ in the type of book experiences they offer: while Four Ways Through a Cave are artist books that are meant to be perused as a method of “reading,” and each word in O is meant to be read, how I considered and used the spine in both projects determined their ultimate expression.

Each book in Four Ways Through a Cave is bound in gray-blue leather. The contents are constructed from blue Xerox prints of black and white drawings featuring textures and the orchestrated score of the Southern Vietnamese national anthem, a song no longer recognized in Vietnam but often played or performed in Vietnam War refugee communities around the world. These prints are layered with repeated laser-cut shapes of banana trees, palms, and bats in a variety of colored papers and comic book scraps from the 1980s Marvel series The ’Nam. Moments from the comics are also pasted onto the pages so that scenes like helicopter rescues, explosions, and phrases like “Get down!” or “Help!” are decontextualized from the war fiction and recontextualized into a dark, musical, and cavernous setting.

These layers then engage with the shape and/or letter “O.” In handset type and in different fonts and styles, the letter is printed across the pages in dark green. These could be read in any way: as a sound, a word, a series of dots, or a sequence of circles. Most people can recognize the musical notation used throughout Four Ways Through a Cave, but few can hear the notes that are indicated, never mind the architecture of the full symphonic score. I wanted the “o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o”s to fill in the aural void between music and imagery: this might be “o” as in “or-ganism,” “o” as in “oc-tapus,” or “o” as in “o-ozing.” Whatever sound you hear in your mind, it is meant to fill your experience of these books with imagined sounds.

The spine and structures of each codex shapes how those “o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o”s function: the whole text block of each book is then cut with a circle so the circle alludes to the opening of the cave; at times, metal flakes shimmer through the circular openings, mimicking NASA’s images of the sun. With each book taking on a different shape and (spinal) structure, the turning, unfolding, and fanning out of pages then proposes four totally different passages out of a fictive cave.

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 1. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 1. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave: 1 takes a lunette or tombstone shape. The codex is formed by multiple folios all cut in the same arched shape that are then interlocked through a folding and tipping pattern, allowing for the codex to form a concertina. I consider each folio to be a spine, making this book multi-spined, with opportunities to open and read from the left and from the right, one page at a time or several expanded at once; the many spines of this book break up the time reading. The beginning of the book, or the top of the text block, introduces the reader to the environment of this cave. As you go deeper into the pages, first laser cut shapes of tropical flora and fauna appear, then war comics, and then, finally, a small circle emerges from the dark texture. Like a moon rising, the circle is repeated page to page, slowly becoming bigger and bigger and placed higher and higher. By the time you reach the end of the book, or the bottom of the text block, the circle is now an exit filled with sunlight.

From one page to the next, each folio acts like a segment of the cave, and each spread then acts like a chapter in the journey. But, by the time you reach the end and the entire book is expanded, the cave looks like a tunnel, and all of the circles allude to light shining back into the burrow of a dark grotto. Laid flat and stretched out, the spines of this book now recede, becoming just a part of the imagery. Time is now expanded from a shorter segment to the long arc of a journey through an ancient rock. “O-o-o-o-o-o-o-o” is an opening and a call through time and space.

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 2. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 2. Photo by Izzy Leung

The arc of time can be witnessed on any clear day by looking up at the sun and following it hour after hour as it travels the path of an arc from East to West. Four Ways Through a Cave: 2 considers this arc in the relationship between the spine and the fore edge of the book. This is a lunette-shaped book turned 90 degrees clockwise, and the contours of this book allude to the cross section of a cave, with the spine representing the opening and the fore edge illustrating the hollow interior.

This diagram becomes completely inverted once you open the book. The one-inch-thick spine—a perfect bound structure adhering approximately 100 pages together—becomes a dark cavity as you turn the pages. Much like book 1, this book also starts with dark, textured pages, and as you read more shapes and comics slowly appear. About a third of the way into the book, circles representing the cave’s exit emerge: at first, they are dark, small, and located close to the spine, beginning on the right side of the book and switching to the left side as the circle is cut through the paper; as you continue, the circle becomes larger and moves towards the fore edge.

About another third of the way through the book, metal flakes start to show through the circle, suggesting that sunlight is near. Flip through the pages in sequence, and the circles start to mime the sun moving across the sky. Turn the pages at a brisk tempo and it could seem like you are fast forwarding time. Flip gently, and it’s as if you are slowing down time. At whatever speed you peruse the book, all of the circles maintain an axis with the spine, making the spine—the depths of the cave—the center of the reader’s gravity.

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 3. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 3. Photo by Izzy Leung

As a reader and viewer of Four Ways Through a Cave, your point of view of “the cave” constantly shifts. In book 1, you see through it; in book 2, you see it from the side; in both, you are immersed in it in different ways. Four Ways Through a Cave: 3 makes you larger than the cave. When closed, the book is a perfect oval with a straight groove cutting the oval in half; using your hands, you can pry apart the book by rotating the two halves of the oval along two covered bolts, one on each half. These two anchor points are the spines that hold the text block together and allow each page to fan out like the wings of a bird.

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 3. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 3. Photo by Izzy Leung

The progression of the pages is similar to the first two books, but the one-to-one scale here aims to empower the reader—that “He” may be as big as nature. Another difference is that the circles do not gradually appear, but rather burst open as a full circle once the reader reaches the back of the book. Completely filled with metal flakes, this full circle represents light coming into the cave; but at this scale, it could also be a face, i.e. you—the reader—looking face-to-face at the sun.

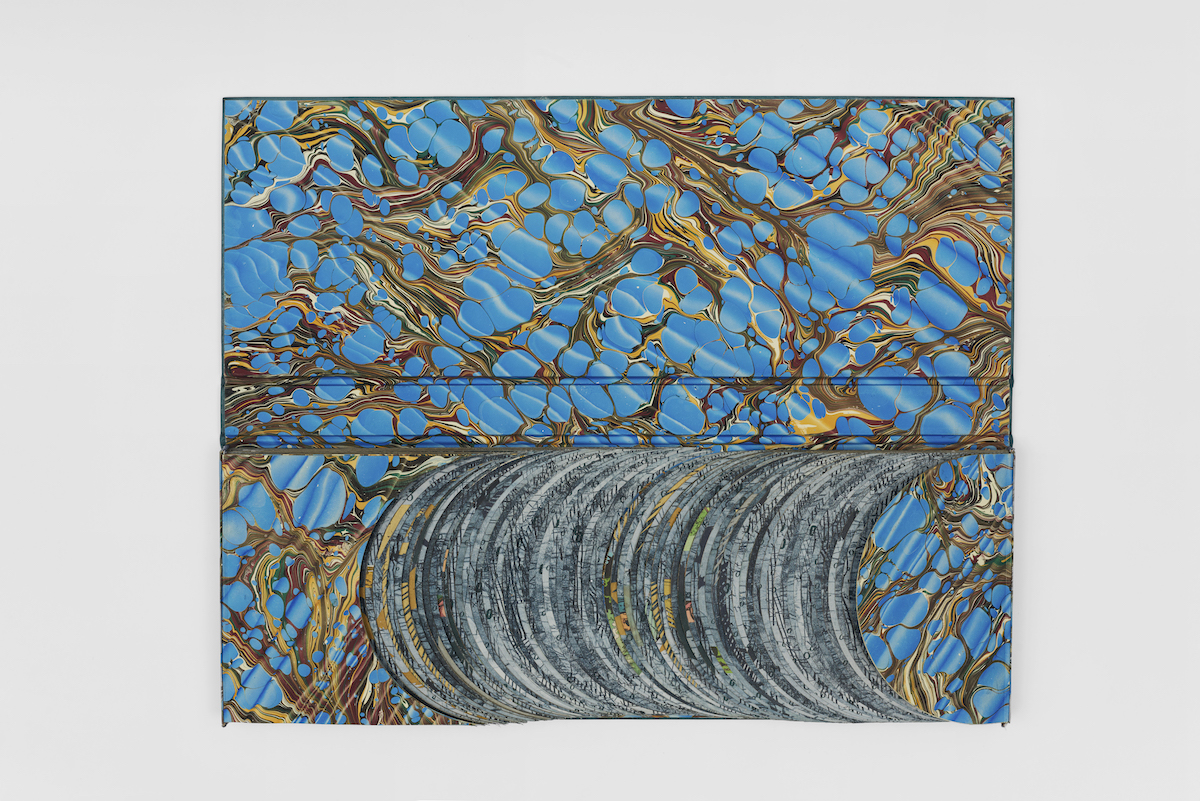

Four Wave Through a Cave: 4 continues the one-to-one scale relationship between the reader and the codex. When closed, book 4 is a simple long rectangle; however, when you open it, the pages are presented to you like a geological formation. From left to right, it appears as though a circle has been dragged out of a whole rectangle, leaving an even trail of paper ridges. There are two spines in this codex, one on the left and right; each is a perfect bind and holds together about one hundred pages as a text block. It is clear that the two blocks were formed from each other: the right side was cut from the left and flipped over, creating a valley in the middle of the book. The left text block follows the same progression as the first three books, but the right presents the pages “backwards,” since it was moved from the left text block and flipped over.

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 1. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 1. Photo by Izzy Leung

Unlike the previous books, this codex is distinctly sculptural, and the pages do not open with as much ease. This is partly due to the structure of the spine, which is the same as book 2, in relation to the shape and size of the pages. Since many of the pages are short, the paper does not rest over the book as you turn the page; rather, the pages want to stick up and need your support to stay open. Unlike book 3, where you have power over nature, here it seems that nature is being resilient against you. This codex wants to stay in its geological formation: whenever you try to turn the page, the structure of the book wants to snap it back into place, as if nature has swallowed all the content into its geology. When you get to the back of the page, the circular sun made of metal flakes appears whole again. Here, you are face-to-face with the sun again, but now the pages want to close in on the sun, suggesting a more challenging power dynamic.

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 4. Photo by Izzy Leung

Four Ways Through a Cave Book 4. Photo by Izzy Leung

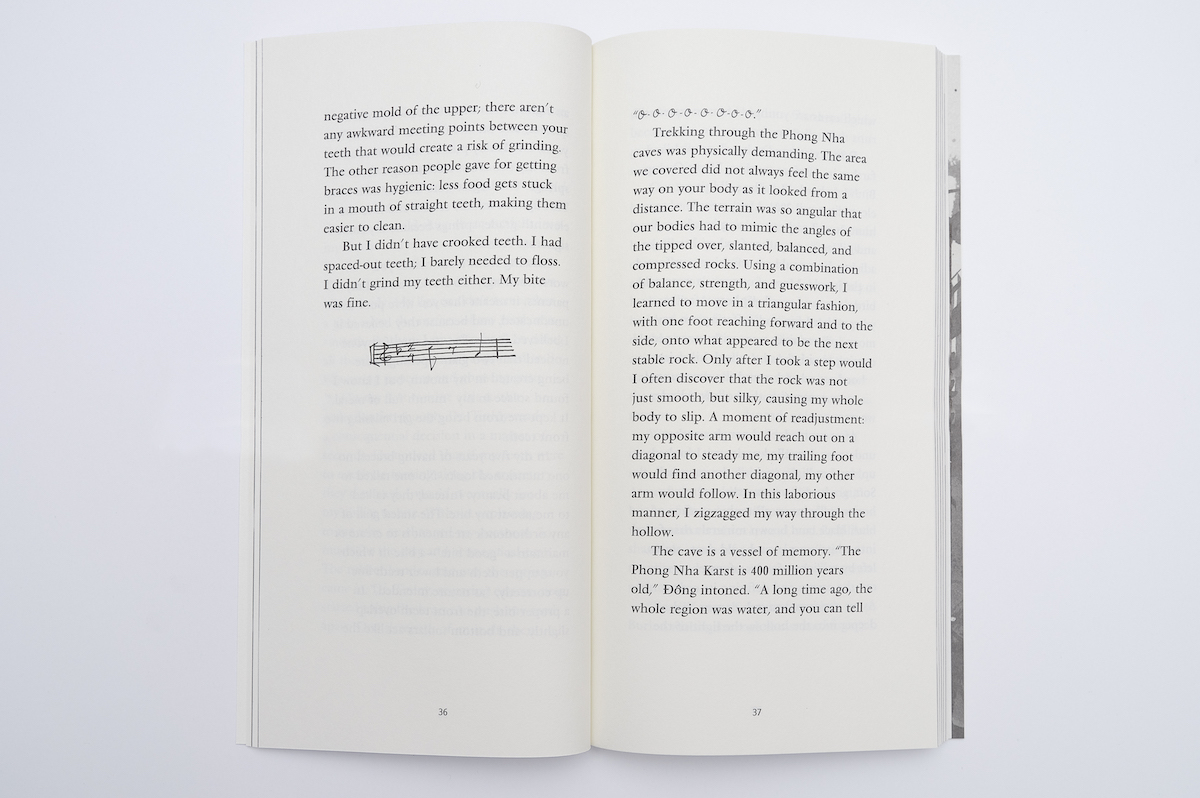

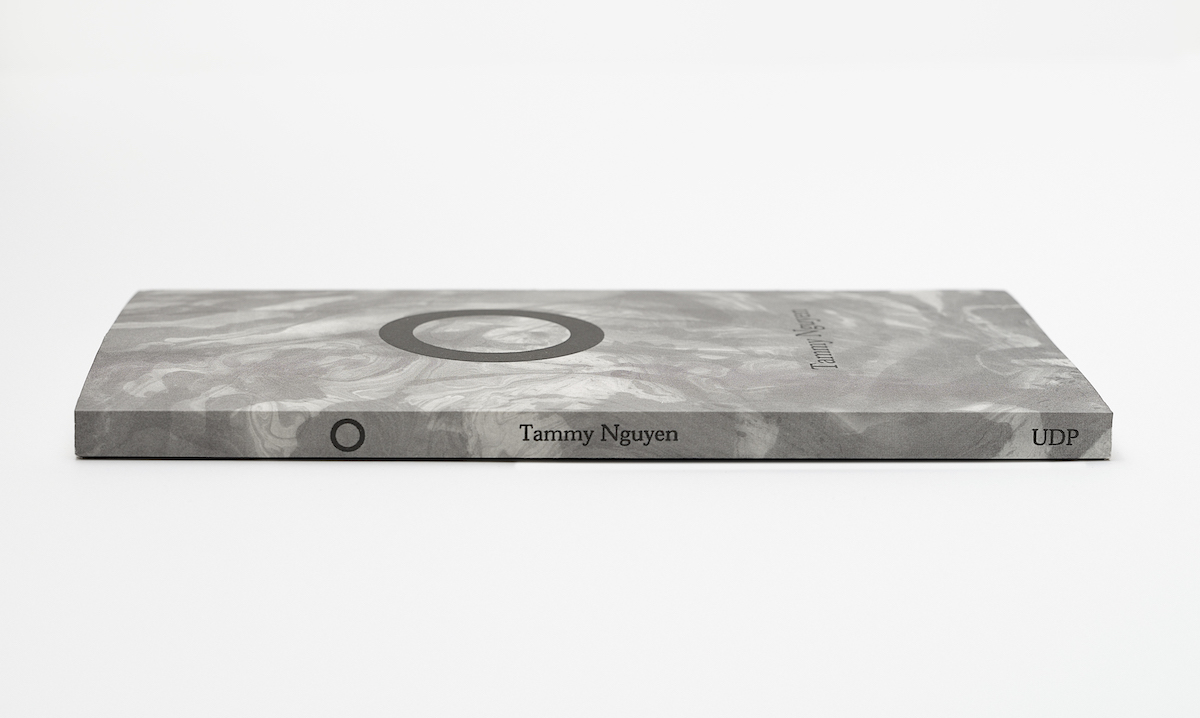

By the time I finished making Four Ways Through a Cave, it was time to design the codex for O, a project that would take the form of an ordinary book and could sit on any conventional bookshelf. O brings together many disparate thematic threads: the book begins with the retelling of my missing teeth that then breaks into a grand description of the Phong Nha Karst. Like weaving, the writing tells of my late uncle David Van, then more about the caves, then more about my teeth. Thinking of the writing as a tapestry, you learn of a man-made island called Forest City, the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the old Vietnamese southern anthem, the making of fake teeth, how a clay vessel is made, the xun instrument, and Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. As in Four Ways Through a Cave, the letters “o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o” appear throughout; however, they are written out as sounds coming from specific people, places, and objects, providing more context for how this should sound in the reader’s mind.

Photo by Daniel Kukla

Photo by Daniel Kukla

“O-o-o-o-o-o-o-o” here is the key to the form of the codex, starting from the spine. When closed, one can see that O is a sewn book split into eight sections—the number eight quietly providing a framework for O before the words are even read—indicated by gray lines that, when closed, emerge from the spine, running up and down the top, bottom, and fore edge of the book. As you read the book, these eight lines open into eight images made of cut pieces of suminagashi paper and ink. Suminagashi is a Japanese marbling technique that begins by dropping ink from a brush into a tray of water; these drops are circles that become distorted by blowing or fanning the surface of the water, creating shapes that look like swirling clouds or mountain ridges. I’m thinking of this technique as an analogy for the Phong Nha Karst, which means “wind carving [Nature’s] teeth.” Many modern-day subjects emerge from these eight pages, such as businessmen, a seafood platter, and mid-century furniture—all ideas that seem far away from the ancient caves.

Photo by Daniel Kukla

Photo by Daniel Kukla

O is approximately eight by four inches, making it open to a perfect square when read, a shape that also fits a perfect “O” and possesses an unarguable center point. The narratives are all written in a descriptive manner and appear almost random until themes and words are repeated over and over again. Of the repetitive moments, “o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o” is the most distinct as it is handwritten in Vietnamese-styled handwriting, a reference to Vietnamese education and upbringing. Look closer, and there is another element of handwriting: all of the Vietnamese diacritics have been handwritten above the Roman letters in direct reference to 20th-century Vietnamese mass produced books. O is set in Vendôme, a French font widely used in Vietnam in the late sixties and onward. To mass produce diacritics, a master copy of moveable type would be handwritten and then reproduced again. These historical references in the typography suggest meaning to the narrative beyond what the words mean themselves.

Photo by Daniel Kukla

Photo by Daniel Kukla

“O-o-o-o-o-o-o-o” always appears as a string of eight “o”s. While you can hear “O” in your mind, the use of eight letters is also a reference to the musical scale. Throughout the book, there are musical phrases that divide each section. So, as the narrative jumps from theme to theme, the music phrase acts as an imaginary transitional sound. But, if you were to play all of the notes, you would hear the former Vietnamese Southern anthem—a song that my family’s dentist in San Francisco helped to write—which can no longer be sung or recognized in Vietnam. This song moves in and out of clarity throughout the book. It is translated into English, and words from the lyrics are echoed throughout the different narratives; but, as musical notes, the song starts to transform into the openness of “O.” In a way, the song, its history, and its integration into the text transforms the music into the different circular symbols, such as the opening of the cave, the sun, my mouth, and the clay vessels.

Photo by Daniel Kukla

Photo by Daniel Kukla

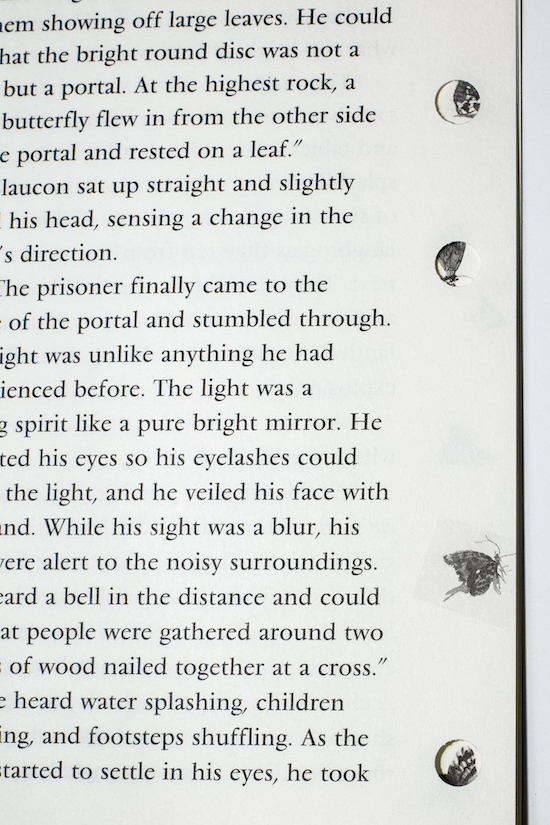

The blurring of meaning is most evident at the end of the book, when Plato’s Allegory of the Cave is retold using themes from the book itself. The margins in this section of the book have been punched every so often along invisible horizontals that have been split into eight increments. At times, imagery can be seen through the holes: you might imagine you see a rock, but after you turn the page, you see that the rock was actually a butterfly. Reading from left to right, the words constantly get closer to and farther away from the spine, flirting with the dark crevice; but, in this last chapter, the holes occupy a space that is more than just the margin. They offer another way to view through. I credit this possibility to the spine, by being a distinct, tight, and dark point of origin, for all things to contrast with, for all things to have a beginning, and point of departure.

__________________________________

O by Tammy Nguyen is available via Ugly Duckling Presse. Four Ways Through a Cave is on view at Francois Ghebaly through August 20.

Tammy Nguyen

Tammy Nguyen is a multimedia artist and writer whose work spans painting, drawing, printmaking, and publishing. Intersecting geopolitical realities with fiction, her practice addresses lesser-known histories through a blend of myth and visual narrative. She is the founder of Passenger Pigeon Press, an independent press that joins the work of scientists, journalists, creative writers, and artists to create politically nuanced and cross-disciplinary projects. In 2008, she received a Fulbright scholarship to study lacquer painting in Vietnam, where she remained and worked with a ceramics company for three years thereafter. Nguyen received an MFA from Yale in 2013 and was awarded the Van Lier Fellowship at Wave Hill in 2014 and a NYFA Fellowship in painting in 2021. She was included in Greater New York 2021 at MOMA PS1 and has also exhibited at Nichido Contemporary Art in Japan, Smack Mellon, Rubin Museum, The Factory Contemporary Arts Centre in Vietnam, and the Bronx Museum, among others. Her work is included in the collections of Yale University, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, MIT Library, the Seattle Art Museum, the Walker Art Center Library, and the Museum of Modern Art Library. She is Assistant Professor of Art at Wesleyan University.