Talking to Poets About Their Love of Crossword Puzzles

Adrienne Raphel Talks to Alice Notely, Fatima Asghar, and More

Anselm is sleeping; Edmund is feverish &

Chatting; Alice is doing the TimesCrossword Puzzle.

So begins Ted Berrigan’s poem, “Small Role Felicity.” “Alice” is the poet Alice Notley; Anselm and Edmund are their sons.

“I think I don’t care about whether I do the puzzles or not,” Notley declared when I spoke to her, but the more we kept talking about them, the less I believed her. Our phone connection crackled. It was snowing in Brooklyn (on my end) and in Paris (hers); I pictured Notley looking out from a balcon as city lights began to twinkle. “I have a completely overactive mind,” she told me. “If I want to relax, I have to be working with words. I either read or do crossword puzzles.”

Notley started doing crosswords when her father died. “I associate them with grief,” she told me. While cleaning her father’s house, she found a collection of diacrostics, a particularly fiendish variety in which you have to fill in a quotation at the center and the name of the author and book title around the side. “I sat and did all of them,” she said. “I didn’t want to think. There was something very vivid about doing them.”

Now, puzzles give her a routine. “I will do one every single night here in my apartment,” Notley said. “I have a schedule,” she said. “It involves getting up, having coffee, checking the news, either going jogging or not. The international New York Times, which I detest now but I buy it anyway, read it, write. In the afternoon, I buy Le Monde. I have lunch. I have dinner. And sometimes I do the puzzle.” (By “sometimes,” I soon learned, she meant sometimes in both English and in French, and sometimes just in French, when the English one is too easy.)

How is a poem like a crossword puzzle? feels like the start to a bad joke. Even though crosswords seem related to poetry on the surface—minute attention to language! love of words! precision!—poets and critics often bristle at the idea of the puzzle, and use it as a metonym for all things that a poem should not be.

Using poetry as a crossword theme is subordinate to the overall puzzle’s logic. You could just as easily swap in something about modern art.

Poems have a delightful history as crosswords. Constructor Jacob Stulberg embedded a whole William Carlos Williams poem through one puzzle. “The Homer that Never Happened,” a 2014 crossword by the late, great constructor Merl Reagle, features a grid shaped like a baseball diamond; when solvers complete the puzzle and “run” the bases clockwise from home plate back to home plate, the squares spell out the last lines of Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s 1888 classic “Casey at the Bat”: THERE IS NO JOY IN MUDVILLE MIGHTY CASEY HAS STRUCK OUT.

A 2017 crossword by Peter Gordon features the following theme answers: WHAT FAMOUS POET / HAS A NAME THAT’S / A DOUBLE DACTYL / EMILY DICKINSON. (The clues: “Start of a question is…” / “More of the question is…” / “End of the question is…” / “Here’s what the answer is…”). But the real star of Gordon’s Dickinson puzzle isn’t in the grid itself––Gordon clued every answer in double dactyls: “Oompah-pah instrument”; “Speak indecisively”; “Footwear with lozenges”; etc.

Some constructors have even used the crossword as an opportunity to test-drive original doggerel. Constructor Frances Hansen composed an original quatrain for the centerpiece of a 2002 Christmas-themed puzzle:

HANG UP YOUR STOCKINGS DO

BUT PLEASE DO NOT SUPPOSE

THAT SANTA YEARNS TO VIEW

SWEATSOCKS OR PANTYHOSE.

In a crossword, poetry is a theme rather than a substantive aspect of the medium. That is, using poetry as a crossword theme is subordinate to the overall puzzle’s logic. You could just as easily swap in something about modern art, say, that hangs painting titles along a Guggenheim-shaped spiral grid; or an astrology theme that puts letters in the shapes of constellations. Poetry in the puzzle is a bonus, never a detriment, but not a necessity.

For a poem itself, being described as a crossword puzzle is––historically speaking, at least––a huge diss. When a poem gets labeled “crosswordy,” it’s usually synonymous for a certain kind of masturbatory difficulty, too clever by half. In 1977, James Merrill published Divine Comedies, which contained “The Book of Ephraim,” a long poem documenting the start of his experiments with a Ouija board.

Though the book won that year’s Pulitzer, the Ouija experiments got mixed reactions. The New York Times review sniffed: “J. M. and his friend arrive at their ideas of the afterlife by using a Ouija board; a teacup moves from one letter of the alphabet to another as Ephraim speaks. In this manner the universe is assembled––rather like a crossword puzzle.” (It wasn’t a compliment.)

During the 1920s, critics like Louis Untermeyer damned T.S. Eliot and James Joyce as “crossword-puzzle-school” writers, relying on pure formal pyrotechnics rather than emotion. According to Untermeyer, The Waste Land’s pleasures were “the same sort of gratification attained through having solved a puzzle, a form of self-congratulation.” A crosswordy poem, in other words, is merely a game, meant to be solved and not felt.

And not only is “crossword” a dirty word when it comes to writing literature, the idea of reading like a crossword is even more gauche. In the introduction to his 2015 Young Eliot: From St. Louis to the Waste Land, biographer Robert Crawford assures the reader that “the verse is nowhere here treated merely as a crossword puzzle or source-hunter’s labyrinth.” (Eliot is a typical punching bag; helpfully for the cruciverbal naysayers, Eliot also had a crossword habit, completing them every day on the omnibus.)

Today, many poets are reclaiming the crossword in the work itself.

Crawford’s description gives a double jab to the crossword. As an art form, the crossword is painted as clever for the sake of cleverness, lacking the sensitivity of Eliot’s verse. As a mode of reading, the puzzle symbolically signals a fact-finding mission, conjuring a reader in pith helmet and blinders who enters the poem attempting to excavate archaeological elements, rather than experience an emotional landscape.

But poetry and the crossword are yoked. Take Notley, for instance. Her deeply personal, committed poems seem to go against everything that crosswords critics would pin on the puzzle—fussy and trivial without capacity for emotional intelligence––the impulses that drive Notley to solve the crossword also drive the elusive yet inevitable connections at the core of her work.

The Descent of Alette, Notley’s 1993 book-length epic poem about the travels of a woman named Alette through the underworld of the subway system, doesn’t borrow its form directly from the puzzle, but it does ask readers to use some of the same strategies that the crossword employs. Like the crossword, Alette breaks texts into chunks of unfamiliar but regular size, forcing the brain to stop and reconsider language phrase by phrase, not as word units but not sentences either. The whole thing hangs together in a cohesive yet disjointed way, and the reader, like the solver, has to put together the world actively.

There’s long been a tradition of poet-crossworders. W.H. Auden was addicted to British-style cryptics, that is, crosswords involving elaborately punning clues. Puzzles find their way like Easter eggs into John Ashbery’s collages. The poet and critic Christopher Spaide has a multi-year streak of solving the New York Times puzzle every day.

Today, many poets are reclaiming the crossword in the work itself. For some, that’s literal. Fatimah Asghar’s “Map Home,” from her 2018 collection If They Come For Us, riffs on a crossword grid: though it looks like a puzzle, the “Across” and “Down” lists read less as discrete clues meant to be solved and more as a poem meant to be experienced in two stanzas. Asghar told me that the crossword, for her, gave her a form to experience “trying to find a way home when you have some of the pieces and not some of the other ones.”

Others, like Notley, let the crossword speak more metaphorically. “If you can really get inside the alphabet, you might really approach the secret of everything,” Notley told me. “It’s a very metaphysical place. Crosswords are the alphabet. They’re not about anything else. They’re pure. I’ve been working on these poems lately where I spell out words vertically. I have a terrible feeling I’m being influenced by crosswords.”

__________________________________

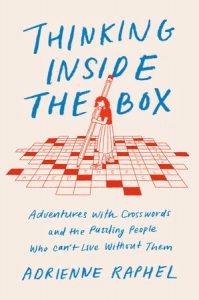

Adrienne Raphel’s Thinking Inside the Box is available now from Penguin Press.

Adrienne Raphel

Adrienne Raphel has written for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, Slate, and Poetry, among other publications. Her debut poetry collection, What Was It For, won the Rescue Press Black Box Poetry Prize. Born in southern New Jersey and raised in northern Vermont, she holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a PhD from Harvard. Her book Thinking Inside the Box is available now.