Talking to Myself: On The Image Book and the Legacy of Jean-Luc Godard

"What Godard is saying has always been a matter of how he is saying it."

When Jean-Luc Godard died on September 13, 2022, at the age of 91, the sense of loss had little to do with what more he might have achieved. No filmmaker of his stature has left behind such vast domains of their filmography which are nearly impossible to see in the US, packed with major works that await rediscovery for decades to come.

What vanished from movie culture feels less like a canonical master than a paradigm for the capacity of cinema to think. As his attention turned to more and more experimental forms over the years, to watch a Godard film was to grapple with an object whose pleasures had as much to do with what the films were trying to convey as in how the meaning-making capacity is activated in the spectator.

Such is the case with Godard’s final film, The Image Book (2018)—although to call it a “film” is not quite right, and not only because it is, technically, a video, but for the ways it defies nearly all our habitual classifications. An oblique montage of film clips, news footage, photographs, paintings, and on-screen text accompanied by a dense soundtrack mixing diverse voices with music by Bach, Beethoven, Arvo Pärt, and other composers, The Image Book is seductive and confounding, concise and inscrutable, a surge of audio-visual materials that feels like nothing so much as the externalization of Godard’s consciousness.

One might say it belongs in the company of experimental film or contemporary art more than cinema (the 60th New York Film Festival is currently looping it in an amphitheater in the manner of a video installation), but even that isn’t quite right. The simplest way to read The Image Book is as the final iteration of a mediatic form Godard invented and refined starting in the late 80s—a text inscribed in a language of his own devising, marked with countless references and influences but beholden to no precedent except its own fiercely committed development.

The most celebrated of these works is the magisterial Histoire(s) du Cinema (1998), an eight-part project, running four and a half hours, that Godard labored over for ten years. At the largest and most legible scale, Histoire(s) constitutes a wide-ranging meditation on the entanglement of cinema with history. It is, in one sense, an epic riff on the dual meanings of the word “histoire,” which translates to both “story” and “history”: cinema as the story of our history; history as the ultimate movie, and one whose moments of beauty flash out from the surrounding darkness of violence, war, and the political horrors of the 20th century.

But that is like saying Ulysses is a novel about the perambulations of a normie cuck going about his business on a Dublin summer day. Moment to moment, shot to shot, and even at the level of the single frame—which may be subject to superimposition, embedded images, or overlaid textual puns, and not infrequently all three at once—Histoire(s) is a relentless provocation to our sensory and cognitive capacity to process audio-visual material.

The work is extravagantly polyrhythmic, syncopated, spasmodic, multimodal, composed largely of film clips subject to various distortions of scale, frame rate, and tonality interspersed with textual materials (puns, thematic markers, fragments of phrases), and paired with a soundtrack so extraordinary that the ECM record label released it as a boxset of CDs in 1999.

Why bother watching a work that refuses to cohere, that poses more questions than answers, that speaks in a highly refined language that perhaps no one but Godard himself understands?

As one is pulled along in this slipstream of materials, themes can be teased out from a sequence of shots, only to be supplanted by a fresh cluster moments later, sending the line of thought in an entirely new direction. At a purely formal level, Histoire(s) is exhilarating and exhausting, exuberant and overwhelming. As for what it all means, Godard situates us in a conundrum. Moving at the speed of thought, the onslaught of information sweeps us up in a hyper-attentive fugue state where our synapses can do little but vibe on the High Modernist razzle-dazzle. Yet the design is far from random, and the text actively solicits and rewards the effort of exegesis.

This is not to say a brave soul might one day undertake a comprehensive skeleton key to Histoire(s) du Cinema, as Joseph Campbell and Henry Morten Robinson attempted for Finnegans Wake, a work to which Histoire(s) is sometimes compared. (The closer literary analogue, I would argue, is Ezra Pound’s The Cantos, with its montage-like clusters of “radiant gists.”) Godard’s video works in this style cannot be reduced to a thesis statement or resolved into fully coherent arguments.

They are, like thought itself, subject to cracks, gaps, failures of signification, contradictions. The intensity of their sensory-cognitive impact is of a piece with their irreducible strangeness, their ecstatic sensuality inseparable from their confounding difficulties. For Godard’s detractors, who never forgave him for abandoning his nouvelle vague riffs on Hollywood featuring manic pixie dream girls, the barrier to entry is simply too high—or worse, unwatchably irritating: pretentious, excessively obscure, ungenerous, narcissistic.

And yet it must be admitted by even his most ardent admirers that if Godard’s video works forged a style of filmmaking entirely his own, absolutely singular and infinitely rewarding, he is also something of a crank who long ago stopped giving a shit if anyone was keeping up. Of the video montages, The Image Book is not in the company of his strongest endeavors: Histoire(s), The Old Place (1999), Origins of the 21st Century (2000), or a personal favorite, the minute-long micro-masterpiece Une Catastrophe (2008). But it does stand as a fitting summation of his prickly genius. It also expresses with particular force and poignancy how cinematic technique, for Godard, is not the means to articulate a set of ideas, but is itself an ethical, thematic, and political practice. What Godard is saying has always been a matter of how he is saying it.

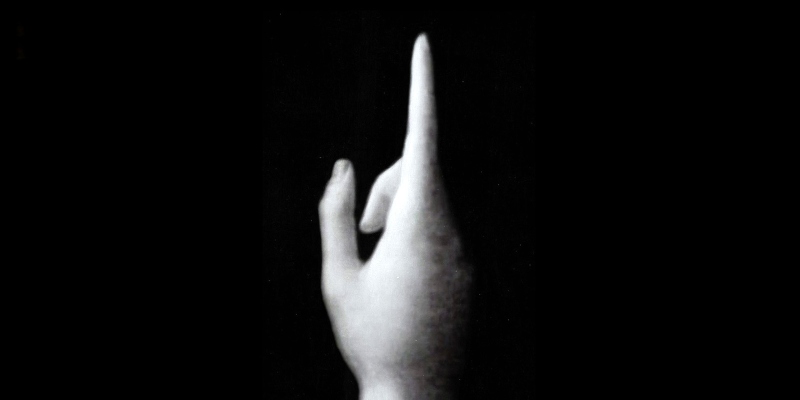

The Image Book is divided into five sections bearing titles that scarcely help decode their thematic consistency: “Remakes,” “St. Petersburg’s Evenings,” “These Flowers Between the Rails, In the Confused Wind of Travels,” “Spirit of the Laws,” and “La Région Centrale.” One can track sets of concerns, or at least general patterns, among some of the sections. “Remakes” functions as a sort of methodological prelude that emphasizes the hand-made, artisanal nature of Godard’s video productions. It opens with a black and white close-up of the upward-pointing hand in Leonardo da Vinci’s “St. John the Baptist,” quickly followed by an over-saturated video of Godard manually splicing strips of film, his cigar-scarred, raspy voice on the soundtrack.

The Image Book is seductive and confounding, concise and inscrutable.

Here, as throughout The Image Book, the subtitling is bafflingly erratic, with large swaths of language left untitled, or select phrases of extended speech given titles. Whether this was an aesthetic decision made by the ever-elliptical Godard or assignable to Kino Lorber, the work’s US distributor, is unclear. Frustrating as this is, the lack of adequate subtitles does have the effect of shifting your attention to formal qualities of the image, the ingenious tempo of the editing, the remarkable textures of sound. That watching The Image Book as a non-French speaker should result in a continuous experience of the failure of language and the precarious nature of synch sound inadvertently reinforces a quintessential Godardian theme.

Another emerges in “These Flowers…” with the frequent images of trains, a motif of longstanding concern for Godard both for its centrality to the history of cinema (starting with the iconic Lumière Brother’s 1895 actualité “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat”) and their historical use in the Holocaust, a catastrophe the filmmaker has reckoned with throughout his career, even as his criticisms of Israel and defense of the Palestinians have led to charges of antisemitism.

Here again one finds Godard reflecting the histoire (story) of cinema against the notion of histoire (history) as cinema. This dialectic is powerfully deployed in the concluding section, “La Région Centrale,” which takes its title from the name of a celebrated 1971 experiment by the avant-garde filmmaker Michael Snow. The region of interest to Godard is the Middle East; the problem he ruminates on is how it has, and has not, been represented in cinema.

What, if anything, unites these sections? What is The Image Book about? Why bother watching a work that refuses to cohere, that poses more questions than answers, that speaks in a highly refined language that perhaps no one but Godard himself understands? There are many ways to answer such questions, the easiest perhaps the simplest: there may be no other filmmaker who commanded cinema at so granular a level, who can make your heart leap by the wit of a juxtaposition, the ravishment of an unexpected image, the virtuosity of his stereo sound effects. (Godard’s soundtracks often create a greater sense of depth, mass, and volume than the images.)

To embrace the interplay of formal mastery in The Image Book with its semi-legible tumult of ideas is to revel in a cinematic experience whose primary effect is to make you think about how you’re thinking, to force reflection on the ways you process sounds and images.

In the closing minutes of The Image Book a woman’s voice ruminates: “When I talk to myself, I speak the words of another that I speak to myself.” Godard shared his mind so we could better know our own.

Nathan Lee

Nathan Lee is an Assistant Professor of Film at Hollins University. He is a former film critic for the New York Times, Village Voice, and NPR, and a longtime contributor to Film Comment.