The city’s Central Bus Station was built upon the principle of a large shed and, except for the enormous windows on one wall, barely disguised as such. Inside, a vast grey plain of concrete was enlivened not only by the dancing dust motes and large, sparkling rectangles of sunlight on the floor, but also by firmly anchored patterns of bright plastic chairs. A schoolgirl entered the building and, veering widely around the chairs, paused at a vending machine. The machine accepted her money, gave nothing in return.

The woman behind a pane of glass marked Enquiries looked away. She touched her stiff hair, pursed her bright lips and tapped the keyboard before her. Small particles of what seemed to be skin flaked from her cheekbones.

A would-be passenger, clutching at baggage and clothing, stumbled into the building as if pushed. Hissing, the doors closed. Outside, a hot wind continued to moan and twist in the angles of the building. The schoolgirl, Tilly, perched at the very corner of one platoon of chairs, and bent her head to her electronic device. Voices in her skull competed for her attention; she did not hear the wind, the doors; had not even heard her own footsteps.

Again the doors parted and an old woman stood between them, holding herself against the buffeting wind and beckoning two small children to join her.

The woman was perhaps 70 years old, the children of primary school age. Each child—a boy and a girl—had a bright backpack. The woman wore loose, colorful layers of clothing and her abundant hair was tied back, silver curls spilling against her skin. She looked around the sunlit departure room and saw Tilly, in pleated private school uniform and hat. Tilly pulled her sleeves down past her wrists, and wrapped her legs around one another so tightly that they might have been woven together and the one loose shoelace the only thing awry. Her eyes were fixed to her phone, and tiny speakers pressed into her ears. Her fingers danced and her lips moved as she breathed some internal voice.

The Enquiries woman shuffled toward the glass doors, a hand flicking at the wrist to gesture that the old woman and children must move away from the doorway. A bus pulled up and, as it lowered itself with a subdued hiss, its door sighed open. Elderly passengers stepped cautiously onto the kerb and, seasoned campaigners, looked around for alternatives to the glossy woman and sliding glass doors that confronted them.

A little group of bodies had attached itself to the belly of the bus, and watched the beast being gutted. Another group began to gather to see it stuffed again.

Tilly turned at a touch and, skilled by habit, unstoppered her ears. Dangling the tiny speakers in one hand, she put her head to one side, and politely performed: Yes, what do you want?

“Where you from, bub?” asked the silver-haired woman, keeping an eye on the children’s ascension into the bus.

“Here,” said Tilly. “From my mother’s belly.” Faltered. “Well, I used to live in . . . I’m at boarding school.”

The school’s name was emblazoned across her small frame: on the round straw hat, the tie, at one breast. Her shoes were sensible shoes, neatly polished; her socks smooth, and folded at the ankle.

“I’m Gloria,” the woman said. “Gloria Winnery.” Her eyes moved to the windows of the bus. Tilly wanted to step around her but could not.

“Who’s your family then?”

“Oh, my mum is white.” It was dismissive. “She passed away.” Tilly glared at the older woman, and continued on to prevent any more questions and to get it over with. “My dad was Jim Coolman.”

“Oh, I’m sorry. You’re that Wirlomin mob.”

“Yeah.” Surprised.

“You poor thing, losing both your parents.”

Tilly gave a little snort. “I only met my dad this year.” She looked past the woman to the bus. The silver-haired woman’s attention moved to the children, who had claimed their seats and were now pressing against the glass. Tilly danced around the colored shawls, the silver hair and waving arm. “See ya,” she said, glancing back from the steps of the bus.

Before he passed away her dad had as good as asked Tilly to make this trip, go to this camp.

“Where you headed, bub?” Gloria called after her.

From beside the driver, Tilly called, “Kepalup,” and kept moving.

Seated near the back, unpacking phone and earbuds, Tilly allowed Gloria a little wave. The old woman was clutching her hands to her chest, as if distressed. Tilly wasn’t feeling so wonderful herself.

She put her bag on the seat between herself and the aisle and leaned against her reflection; beyond that was the rush and flow, the spiky, shape-shifting world of traffic lights, of shouting signs, of corners of glass and brick and steel, of vehicles merging and separating; people were fragments and shadows in tilted panes of glass and scattered shards of sunlight. Tilly’s fingers gripped each shirt cuff; her fingernails were gnawed to the quick. Smoothly, with the practiced ease of a nervous reflex, those raw fingertips found the text from her Uncle Gerry:

Hi Tilly get Esperance bus to lake grace 2moro. Someone will pick you up there for the camp. Gerry.

She’d replied, Ok, and a phone call from Nan Kathy had sorted it. Gerry was her dad’s cousin, Noongarway; connected by generation from an apical ancestor, as the legislation speaks it. Before he passed away her dad had as good as asked her to make this trip, go to this camp. “For me,” he might as well have said. “For all of us.”

Tilly told herself it was nice of the old woman (Gloria?) to be concerned about her, but she’d rather she wasn’t. One of the children at the front of the bus turned, waved to Tilly. Did they know about the taboo, too?

She caught the driver’s glance in his rearview mirror. Closed her eyes.

*

Already, several of the passengers had turned to look at her, some more than once. In some cases, they had gone to some trouble to do so, and smiled reassuringly. Tilly did not feel comforted. People had told her not to see hurt where there was none, not to be paranoid. Trust yourself. Even Gerry had said it. Love yourself. Be grateful.

She administered to her telephone. Her reflection there, too.

Outside the bus, unnoticed by Tilly, was clear evidence they’d left the city. White lines stuttered along the bitumen and Christmas trees trumpeted orange blossoms from fence corners and road edges. The many masts of a forest of some other tree, tall and straight, sailed by. For a time, the bus sliced through undulating, bright yellow rectangles that were irregularly hemmed by fences, only otherwise interrupted by a thin line or threatened stand of shabby trees crowning a slope. Vast expanses of bright yellow flowers rippled when the wind rolled across them.

Tilly was so attentive to her screen you would not think she realized two old women were talking about her. Each turned their head to look, turned away again. Their skulls leaned to one another. Tilly pulled her wrists deep into her shirtsleeves. Sipped at a water bottle.

“Pulling over for a toilet break.” The driver’s amplified voice startled her. “Back on the bus in 15.” He made a performance of looking at his watch and named a time. “Grab a snack if need be. We’ll pull up again around lunchtime.” He rose to his feet, singing, and the passengers, save those few laughing and singing with him, went among the billboards and bowsers, headed for bright shelves and cellophane.

It wasn’t one of those new roadhouses, in which everything is integrated. Vehicles, except those re-fueling, parked haphazardly at a distance from the bowsers. There was a little copse of peppermint trees; green, mowed grass; and a path to the toilet block. From behind a tall fence, two llamas stared at Tilly with impertinent expressions. A sign:

You can feed the llamas!! Feed $1 per bag in shop.

Another on the toilet wall:

These ARE NOT public toilets. They are privately run.

Please do the Right Thing!

If you need to use our toilets please use the shop also. Thank you.

Inside the door, large above the basin, in strong red letters:

NOT DRINKING WATER.

Tilly went into the shop. With a twinge of anxiety, she passed her fellow passengers going the other way, back to the bus. She grabbed a bottle, handed the man some money. Checking the change as she left and realizing she’d been short-changed, Tilly turned around within the doorway. The shopkeeper was smirking; it seemed the skin of his face might split. He teetered toward her with a curling index finger.

The bus shot between two paired trees as if through a gate.

Tilly turned her back on him.

Back on the bus, Tilly pulled a bright plastic lunchbox from her backpack. Gave it prime place among her luggage.

Trees closed in on each side of the road, then were flung back again and reduced to scattered clumps, or a thin fringe running beside road or fence and the expanses of bright yellow. “Canola,” she heard someone say, though not addressing her; people looked away at her glance. The undulating yellow was a backdrop, a blanket, something you might fall back upon. Be helpless and pinned down, held there and hurt by some greedy twisted fucker.

Smothered under this sky.

Tilly pressed her knees tightly together, folded her arms very tight.

One of the women across from her held out a plastic container of sandwiches. “We’ve made ourselves too much, love. Help yourself.”

“Oh no. Thank you very much, but I’m full, really.”

The old woman smiled, but seemed disappointed. Before she could withdraw Tilly seized and displayed her own open lunchbox. “Something sweet to finish off?” The plastic box was brimming with brightly iced cupcakes. “I baked them for the trip.” The women’s faces creased and folded, crumpled with pleasure. They struggled to rise from their seats. Two pair of little old hands reached toward Tilly, fingers trembling. “Baked them yourself you say?”

“Yep, got up early especially. Ate too many already, myself.” Though in fact, she had eaten one.

“Mmm, taste even better than they look.”

“Aren’t you the clever girl then?”

Tilly closed the lunchbox when they’d had their fill, and clamped herself back into the music.

*

Road signs held up words and made them strange. She realized they were not from any song or film or book she knew: Wagin, Narrogin, Kojonup, Katanning . . . Wangelanginy Creek: a place, it might be said in the old language, where all the voices are together speaking and where, perhaps, beyond the roaring tunnel of glass and metal that held our Tilly, some innocently babbling brook remained, some safe and sheltered course with its own momentum continuing.

Tilly removed her tie and curled it in the hollow of her upturned hat.

At the next stop, the driver—stretching and scratching himself as Tilly stepped from the bus—asked, “Where you getting off again, love?”

“Lake Grace.”

“Staying there?”

“No. Kepalup, or Hopetown.”

A passenger glanced quickly at her, then away again. A woman on her way to her car turned her head at the name and two women leaning against a car watched the bus leave.

Tilly was wrapping herself in her playlist, her photos, all her friends and the world she wanted kept close:

You lubbly sing Watta dog

Yey party bitches

Thas rite niggas u 2 blue.

Tilly took the lunchbox from her bag, looked at the cakes for a while. She snapped the lid shut, put the box properly away. Sipped water.

Attending to her homework, Tilly made her way into some old novel: Dracula.

On the long scar of bitumen ahead, a minor murder of crows prepared to have their feathers ruffled. A couple took reluctantly to their wings, a few hopped away from the furred carcass as the bus buffeted them. Further ahead, a bloated kangaroo thrust its limbs skyward.

Tilly, bent to the old English words on her small screen, may not have noted the shadows lengthening, or the vegetation changing. Outside, mallee bristled at the bus’s approach, then writhed and thrashed and shivering leaves applauded the blustering vehicle’s departure.

Despite the fine soil lifting in the wind, shadows remained etched in earth: trees and fence posts, clods of ploughed soil, even a bull ant defiantly gripping the road’s bitumen edge.

A thin stand of towering trees closed above the speeding bus, and in that brief tunnel of filtered light the trunks and limbs referenced the barely sun-kissed flesh of most of those in the bus; might have reminded them of their own sheltered, intimate parts; Tilly’s secret skin too.

Deep red gum oozed from old wounds on the scarred trees; dark fluids seeped and coagulated.

The bus shot between two paired trees as if through a gate. Sinking into some old story, Tilly was slipping away from her new friends, their fashion and idols, their boyfriends and bands, their films and photos and gathering energy. Even so, she did not see the clefts and limbs, the gateway of trees, the eagle hovering far above. She heard no rattling leaves, no shivering applause.

Lest we forget. The Great War.

One side of the road was forest reserve, mostly what’s called jam tree. Small, erect trees standing shoulder to shoulder like a sullen crowd, dull with dust. The other side of the road was bare earth, a haze of soil hanging just above the surface and sand heaped at the base of fence posts. Clouds moved across the bare sky, slowly shape-shifting.

Tilly raised her head. Saw the glass screen beside her. A dead snake on the bitumen. More crows. A shallow pool by the road held a patch of blue sky that rippled. The bus swerved a little.

“Lake Grace coming up. One passenger getting off here, cup of tea and toilet in another hour if everyone can hold until then please.” It wasn’t a question.

Tilly read the speed signs. Saw a jeep, recently polished and ostentatiously parked across the entrance of a driveway. Three metal cut-outs of a poppy flower leaned in its open cab. The town labelled with a metal sign. The same colorful metal poppies again, each the height of a person, standing around the fence of the preschool.

Lest we forget. The Great War.

Farm equipment: For Sale. A pub. Supermarket. Curly Wigs Hair Salon. Eatitup Café. Guns Safes Steel.

The bus pulled over at a roadhouse the other edge of town. “Got someone to meet you, love?’

“Yes thanks.”

But there was no car waiting at the roadhouse.

Faces in the windows of the bus turned to her, for a moment like a school of fish. All eyes on Tilly, on her backpack and the Aboriginal flag imprinted upon it.

“Tell you what, love, have a word with the roadhouse. You got money? You can wait in there, at a table. He won’t mind if you just sit.”

Not 50 meters away, the proprietor held open the door. He was a big man; Tilly would need to press against him to get through the door. His shirt tight against his bulging belly; skin like damp beach sand; strands of dark hair pressed against his skull.

Then there was the sound of another engine, of tyres flicking small stones. The school of faces in the bus windows turned again, lured by glass and sunlight-edged chrome. A dented and dusty four-wheel drive utility pulled up parallel to the bus, facing the other direction. The utility’s tray cover was torn, and a thin cord dangled by a broken taillight. Its motor coughed and grumbled. The girl stood in the space between the two vehicles. The bus driver looked down the tunnel of his open doorway. The faces in the bus floated this way, that, like coy goldfish not wanting to stare.

The ute’s tinted passenger window opened slowly, teasing the curiosity of the passengers. The onlookers saw two men inside. Twins? Of Aboriginal appearance. Approximately 30 to 40 years old. Unshaven. Passenger appeared to be drinking, your grace.

“Tilly?” said the man in the ute. He gave a small belch.

“Gerry?” Tilly said, looking from one to the other.

“G’day, Tilly,” said the driver.

“Gerry,” she repeated, relieved.

“Hop in.”

The bus throbbed, waiting.

That girl in school uniform, no tie or hat; socks down, her skirt surely too short for school rules. She had flounced from the bus, now leapt into the back seat of the dual-cab. Kept her backpack with her, not in the tray.

“Yeah, plen’y room in the cab, Tilly. You don’t want your bag in the back. Blood and all sorts of shit there.”

They accelerated away before the bus door had closed.

The roadhouse manager, still with one hand on the open door, raised the other in a wave of departure and the car horn squawked a reply. He looked at the bus, and gave a gap-toothed leer.

Eyeballs rolled away with the bus. The roadhouse door closed.

__________________________________

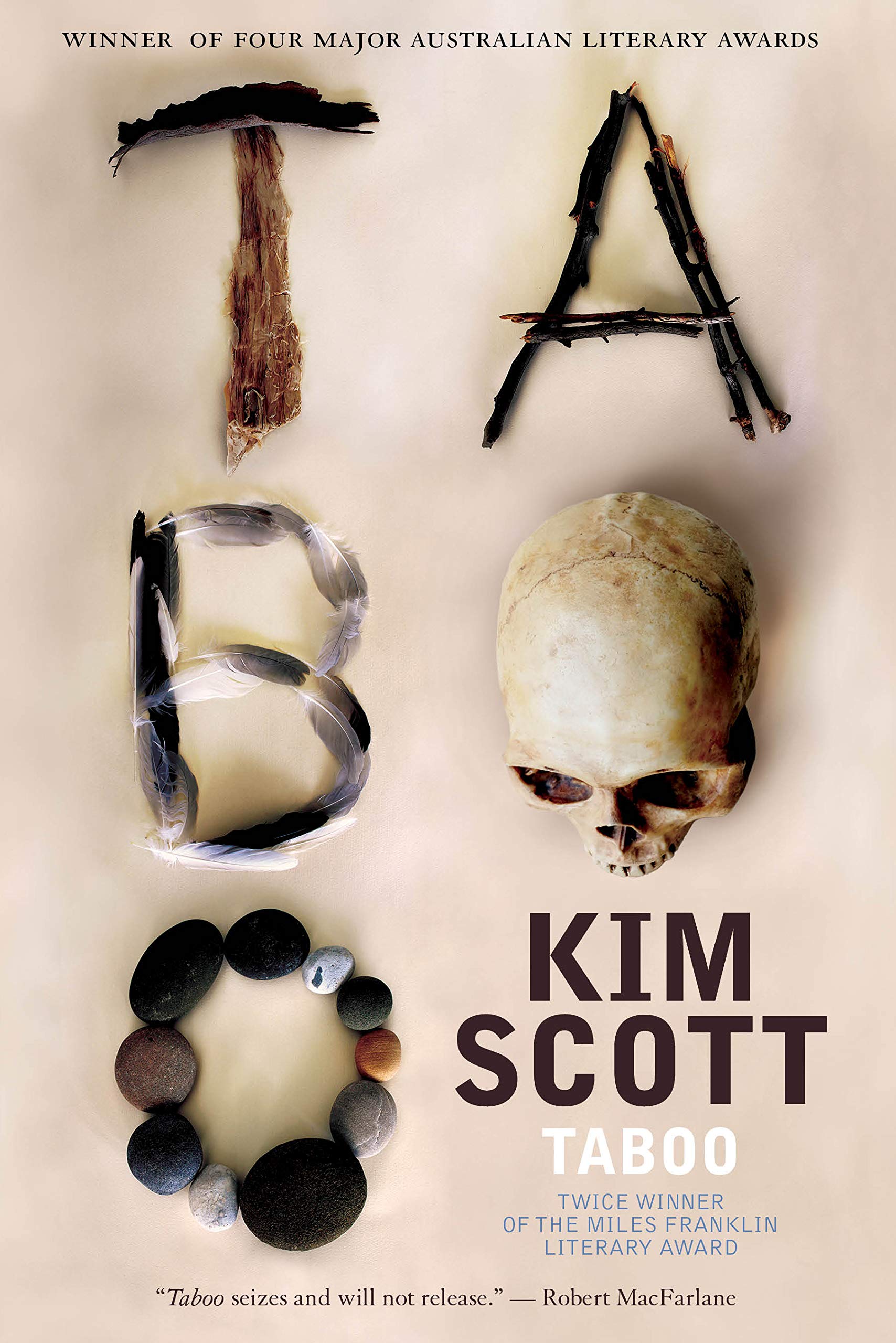

“Departure” excepted from Taboo copyright © 2017 by Kim Scott. All rights reserved. “Departure” first published in the Review of Australian Fiction, 2015. Taboo first published 2017 in Picador by Pan Macmillan Australia. First published in North America in 2019 by Small Beer Press edition.