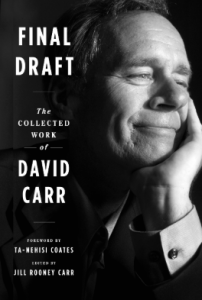

Ta-Nehisi Coates: On the Privilege of Knowing David Carr

"This man was rare. I knew it."

It’s still odd, after all these years, for me to think of David Carr as a writer. The broader world knew him as a writer, of course, and an accomplished one. David had a sprawling career that found him writing for alternative papers, doing longform magazine work at The Atlantic, New York Magazine, and Washington Monthly, and then finally as a writer for the New York Times, where he did everything from essays to straight news to (perhaps most famously) a column covering media. In 2008 he published a book—The Night of the Gun, an ingenious memoir in which David interrogated his own memory by interviewing the characters interspersed throughout his own rousing biography. Along the way, David cultivated sources and readers, collected friends, and enraged enemies. It is an enviable record, one that speaks for itself.

But there was the David the world knew and the one I knew. I met that latter David when I was a 20-year-old faltering college student who had some vague ambition of being a writer. David was then one year into his stint as editor of the Washington City Paper and was, most importantly for my purposes, hiring interns for the summer. My application was underwhelming—a chapbook of poetry and some middling columns and reporting I’d done for my college newspaper. But David was looking high and low for storytellers, and he did not much care how or where he found them. I was hired for the summer, then extended as a staff writer, and for the next three years David both invigorated and terrified me.

David’s staff skewed under 30, and among them I was distinguished neither by talent or hard work. But David invested in me, if not in dollars, then in something more precious—time. He line-edited much of my earliest work—shifting sections, urging me on with comments, threshing wheat from the chaff. He was a stickler for names and facts—and if you missed one, he would think nothing of yelling at you and threatening your meager livelihood. I wonder now if all of that yelling was necessary. Probably not. But you take the bad with the good, and there was so much good.

David could be a terror when you got it wrong, but when you got it right—when you wrote something that made him smile—he’d make you feel like you’d hung the moon. I can remember coming to his office after closing a piece on day laborers and him looking at me and saying, “I was just talking about how fucking great your piece was this week.” I was a kid who had never felt like he’d done anything great for anyone. And it was only when working for David that I came to understand that I might actually be “good” (to say nothing of great) at anything. Part of that realization wasn’t just in what David said about my own work, but where he set the bar. David would bring in writers from Vanity Fair to hold workshops with the staff. He’d introduce me to journalists who were doing incredible work. He’d clip articles from the New Yorker or Esquire and leave them on my desk with a note attached: “This is the level of work I expect of you.”

That kind of care and regard for young writers rarely happened in the ’90s, when I met David, and happens even less now. And what followed in the wake of that mentorship was just as rare—David became my friend. What I remember are dinners out in Montclair with the Carr girls, lunches where he’d dispense the latest media gossip, pancakes at his cabin upstate. David didn’t just love me, he loved my wife and my son. He always asked about them and would amuse them both with his wild stories and unique vocabulary—“Carr-isms,” we called them. If he’d been working especially long hours, David would say he’d been “in the weeds” all week. Or if he had some secret to bestow, he’d say “this is just girls” talking. Later this evolved into taking a trip “out to girl-island.” Carr-isms aside, David had an inbuilt sense of the significance of family ritual that I lacked. You didn’t go visit the Carrs and sit around and watch TV. You played touch football. You hiked. You rode bikes.

He worked us all so hard, as an editor. And then, as a writer, he worked himself even harder.David was a ferocious advocate of those he loved—his efforts on my behalf are matched only by those of my wife and parents. He was violently loyal. Once, he heard an editor I’d worked with disparaging me in front of a bunch of other editors, at a time when I was on unemployment. David, as was his wont, informed the editor with a flurry of colorful language that no such further talk would be tolerated. I don’t think I’ll be getting more friends like that in this life. I knew that at the time. I used to stop past the New York Times building to stand outside with him and shoot the breeze during a smoke break. I didn’t even smoke. It didn’t matter. This was rare. This man was rare. I knew it. And when people like this have time to bestow upon you, you take it. You take as much of it as they will give. My only regret is that I did not take more.

I guess it’s for that reason that I am particularly thankful for Final Draft. These pieces represent one last conversation with David. Much of what is here I’d read at the time of publication, so the most striking material for me is the work David did while in Minnesota and in his emergence from rehab. It’s in his own self-assessments, as a recovering addict and a father, that I see an earlier David that I did not have the privilege of knowing. But my interest in this earlier portion of the book is a subjective judgment.

More broadly, what you see in Final Draft is not just the thing that was hard for me to recognize as a former pupil—that David was a writer—but that David was a writer of uncanny gifts. He was already, as a relatively young journalist, in possession of the easy voice and understated humor that would later bloom in his later work for the New York Times. He didn’t waste his readers’ time, and he knew how to get to the heart of the story with velocity. In memorializing Brian Coyle, a politician fighting the good fight, a young David wrote:

Brian Coyle made certain that his fight to live with AIDS became a very public one. Dying with the disease was necessarily a private matter.

And just like that, you’re in the story. No throat clearing. No hemming or hawing. No philosophizing on the nature of death. You see the same efficiency years later when David profiles Robert Downey Jr.:

Look at him standing there, a great big movie star in a great big movie, the Iron Man with nary a trace of human frailty. A scant five years ago the only time you saw Robert Downey Jr. getting big play in your newspaper came when he was on a perp walk.

There’s the whole story in two sentences—a hero once laid low, now back in the saddle. And then there is David’s sheer fearlessness, which bled over from the man onto the page. For thirteen years, he was a media reporter for the Times, writing a column for the business section for nine of those years. This latter venture was something of a promotion, but it was also a risk. Columns are where great journalists go to die. Unmoored from the rigors of actually making calls and expending shoe leather, the reporter-turned-columnist often begins churning out musings originated over morning coffee and best left there. But David rarely, if ever, published a column without calling someone—often people who were, themselves, the subject of that particular column’s ire. For that reason, David’s columns had heft without devolving into an unwieldy mess of “on the other hand.”

That style of reported, researched, pointed opinion reached its apex in David’s exposé of the billionaire Sam Zell’s purchase and pillaging of the once great Chicago Tribune. This was a story made for David, who loved newspapers and hated bullies. Through detailed and damning reporting, David showed how Zell acquired the Tribune with little of his own money, transformed its offices into a frat house, decoupled the Tribune from its journalistic reputation, and then paid his execs millions in bonuses. It was a tour de force of journalism and in so many ways presaged this tragicomic era.

No one had a better sense of the brevity of life, and how essential it is to live as much of it as we can.How many times have I wished David was alive right now? Media—from mainstream to tabloids to reality TV—was instrumental in the rise of Donald Trump. David would have loved this story as much as he hated its implications, and very few reporters would have been more equipped to detail those implications. But David is not here. And our coverage, and our country, is poorer for it.

Some of David’s journalistic gifts were obvious to me at the time. Many were not, and even those that were, I poorly understood. He worked us all so hard, as an editor. And then, as a writer, he worked himself even harder. I could see this at the time, but now reading Final Draft, I wonder how much of that was rooted in his earlier brushes with death and his constant struggle with sobriety. When I was younger, I imagined substance abuse as a foe David had conquered—a slain dragon. Only later did I understand that the dragon was reborn each day, and every morning, David had to wake up and go off to battle.

David won much more than he lost. And I think those victories were tied to this fact: No one had a better sense of the brevity of life, and how essential it is to live as much of it as we can. I think now that that is why he worked so hard—that the work (and the play) was how he fought back. And I now think back to David as an editor, and think that’s what he wanted most from us. To battle, every day. To wake up in the morning, ready to face the dragon.

__________________________________

Excerpt from Final Draft by David Carr. Foreword copyright © 2020 by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Feature photo by Brian Lambert.