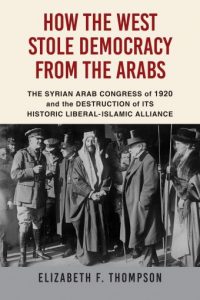

Syria's Doomed Struggle for Independence After WWI

Elizabeth F. Thompson on a Diplomatic Ruse That Transformed the Middle East

It is a commonly held idea that there is but one democracy in the Middle East. Not only is this false, but the ways it is uttered—as if the region has been one long failed blood battle for centuries and centuries—overlooks the fact that democracy was on the verge of flowering at the end of World War I. During the war, the British promised the Arabs an independent state, and in return, leaders of the Arab Revolt joined the Allies in World War I to capture Greater Syria from the Ottoman Turks in 1917-1918.

Prince Faisal, leader of the revolt’s Northern Arab Army, proclaimed the end of Turkish tyranny and a new era of constitutional government, where citizens would enjoy equal rights regardless of religion, upon the army’s arrival in Damascus in October 1918.

And here began the beginning of a deep and profound betrayal.

Not long after his troops ousted the Ottomans from Damascus, the British informed Prince Faisal that Arabs would not automatically gain independence: they would have to negotiate for it at the Paris Peace Conference. Prince Faisal traveled to Paris, where he won Allied recognition of provisional independence on condition that Syrians accept a temporary period of political tutelage, called a mandate. He then returned to Syria to call for elections of a constituent congress, which presented its resolutions on Syria’s political future to a visiting American committee of inquiry sent by President Woodrow Wilson.

The congress called for immediate independence, or at least, a brief and limited American mandate. However, the British and French refused to recognize the congress or its resolution. They had secretly agreed that France should occupy Syria and Lebanon, while Britain occupied Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq. In the fall of 1919, Britain withdrew its occupying troops from Syria, making space for a French occupation. Popular protests flared across Syria that winter, and the Congress reconvened to declare unilateral independence, without Allied consent, but based on the League’s principles of self-determination.

In January 1920, Faisal returned from another round of negotiations in Paris with a secret accord to avert outright colonization. By then, the French had occupied coastal Lebanon and Syria and installed a high commissioner in Beirut, General Henri Gouraud, who itched to occupy the Syrian interior, including the Syrian capital, Damascus. The accord, struck with French Premier Georges Clemenceau, permitted a limited form of French mandate that would bar French troops from the hinterland.

But Faisal feared the power of political movements that rejected all compromise in favor of full independence. In hope of moderating popular opinion, the Prince enlisted the help of a famous Islamic reformer, Sheikh Rashid Rida. Rida, well known for his widely read magazine, The Lighthouse, and for his support of constitutional government had been living in Cairo during the war, in exile from Ottoman Turks.

The negotiations conducted at Damascus in February and March 1920 would lead to the Syrian Arab Kingdom’s declaration of independence on March 8th. Virtually every invested faction attended. Negotiators included not only the dominant Sunni Arabs, but also Shi`ites and Christians. Jewish and Greek Orthodox leaders pledged allegiance to the constitutional monarchy.

The negotiations did not include Faisal’s own father, Sharif Hussein at Mecca, who had led the Arab Revolt. Arabs of Greater Syria had insisted that their state would be independent from the Kingdom of Arabia, but in federation with it. Likewise, they aimed to forge a federation with the Arabs of Iraq. Their model was the federal system of the United States.

Rida warned that the French were laying a trap. Their advisors must not hold any administrative authority in the government, he advised. Syrians must be free to disagree with French advice.

Remarkably, the Arabs in Syria formulated their political demands in alignment with what they understood to be international law. Arabs were not flouting European liberalism, they were universalizing it. At stake in 1920, according to Rida, was not just the independence of Syria, but the viability of the peace after World War I. He correctly foresaw that if the rights of small nations were not respected under the new world order, years of violence would ensue.

Arabs were not alone in the demand for national rights and the end of colonialism after the war. Indians, Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese and colonized peoples of Africa were also clamoring for self-determination, inspired by Pres. Woodrow Wilson’s wartime promises. As Rida predicted, the denial of democracy at this critical moment, in 1920, unleashed decades of anti-colonial and civil violence across Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Also at stake was the future of democracy in Arab lands. Sheikh Rashid Rida was in a unique historical position to forge a compromise between religious conservatives and secular liberals in the Arab world. The political bargains he struck at Damascus in the early spring of 1920 were historic. The destruction of Syria by French forces four months later would drive a wedge between Islamists and liberals that lasted for a century, dividing the coalitions that rose up against dictatorship in 2011, thus undermining the Arab Spring. This was exactly what Rida hoped to avoid when he set out to Tripoli just after New Year that January.

*

A rainstorm drenched Qalamun on the morning of Sunday, January 11th, when Sheikh Rashid Rida and his brother set out on a walk to Tripoli. The road turned muddy, so they stopped at the house of a friend, the city’s former mufti. Because of his nationalist views, the French had expelled him from his office. Suddenly, a French messenger arrived with a note from General Henri Gouraud, the French high commissioner in Beirut: would Rida kindly attend the official welcome ceremony for Prince Faisal upon his arrival in Beirut on Wednesday?

After tending to his ongoing legal tangle over the mosque endowment, Rida set out for Beirut the next evening. The trip took six hours. Rain poured down and one of his car’s tires blew out. He arrived near midnight. On January 14th, Faisal disembarked at Beirut to enthusiastic crowds. General Gouraud hosted a reception and luncheon for the prince, attended by his top military brass as well as foreign consuls present in the city.

Faisal assured Gouraud that the Clemenceau accord would open a new era of peaceful relations in Syria. Gouraud warned him that France would uphold the accord only if all guerrilla violence ceased in the Bekaa valley, which lay between the French and Arab zones. The general sent a guardedly hopeful report back to Paris.

The next morning, January 15th, Rida arrived at the Damascus government’s delegation in Beirut for a personal meeting with the prince. He had been waiting for this moment since September. Faisal arrived just before noon. “He welcomed me with much praise,” Rida recalled.

The 35-year-old prince and the 54-year-old sheikh took an immediate liking to one another. Over the course of more than an hour they spoke frankly. Faisal confided to Rida the terms of the accord with Clemenceau. Since America and Britain had abandoned Syria, they must strike a deal with France, he explained.

Rida warned that the French were laying a trap. Their advisors must not hold any administrative authority in the government, he advised. Syrians must be free to disagree with French advice. And the French must not be allowed to control the police or military. “Their control over security, for example, would allow them to rob the country of its freedom,” Rida pointed out. “I cannot be free in my thoughts or opinions, or in advising my nation against their policy, if they can boot me out of the country for security reasons!”

“That is true,” Faisal admitted. “But if we are united in the service of our country, we can protect ourselves against the dangers inherent in their authority.” The only other option would be to wage war, Faisal reasoned, and he would not take responsibility for that: it was up to the people to choose between the accord and war.

Rida proposed to Faisal a third option. “If they would let you say at the Peace Conference that Article 22 of the Treaty recognizes the complete independence of Syria,” Rida proposed, then Syria could act as a strong nation. It could choose its own advisors, not France. And Syria could “form a national government, elect deputies to the legislature, and enforce the laws.”

Some theorists and policymakers interpreted “nations” to mean “states,” meaning the Syrian state was essentially sovereign. Others insisted that the article did not grant political sovereignty.

International recognition of Syria’s independence would also remove the threat of conquest, Rida argued. “The French Chamber of Deputies will not approve funding for a war of colonization, especially against a country that the peace conference had determined was independent.” Rida demonstrated here familiarity with debates on Syria in the French Chamber of Deputies. Since the 1918 armistice, the socialist deputy Marcel Cachin had led a faction demanding respect for Syrian self-determination.

Faisal parried that the colonial lobby would be likely to prevail over pacifists in the Chamber. “[France] feels the ecstasy of victory,” he remarked. “Syria would consider an order to evacuate her army occupying Syria as an insult to her military honor.”

Rida’s counsel reveals that he was acutely aware of the ambiguities of legal meaning in the League covenant that could either ensure Syria’s freedom or seal its subjugation. Article 22 provided that “certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory.” Article 22 left open to debate where sovereignty lay—with the nation, with the mandatory power, or with the League of Nations.

Some theorists and policymakers interpreted “nations” to mean “states,” meaning the Syrian state was essentially sovereign. Others insisted that the article did not grant political sovereignty; as a mere nation, Syrians, like Zionist Jews in Palestine, could lay claim only to a homeland, not an independent state. They would remain under the sovereignty of the League (or a mandatory power designated by the League) until they proved the capacity to govern themselves and “to stand alone” in world affairs.

Most radically, the British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour would insist in 1922 that mandates belonged to the conquering power. The League was bound to become a “laboratory of sovereignty,” as one scholar put it. It would take years to define the terms of statehood.

In Rida’s view, Syria must exploit this legal ambiguity. Its future depended on obtaining an official pronouncement in favor of the “state” interpretation of Article 22. That was the reasoning behind the Syrian Union Party’s call to draft a constitution for presentation to the Paris Peace Conference. It would prove that Syrians were worthy of a state.

Rida would later claim that he was the first to propose that Syria confront the Allies with the Declaration of Independence as a fait accompli. He was, in fact, only the herald that introduced the idea to the prince. The Syrian Congress had already adopted such a resolution on November 24th and deputies had repeated it to Faisal at an Arab Club meeting on January 22nd.

Rida and other Syrians saw themselves as players in a global process of establishing a new regime of international law to govern the relations among states. At stake in the Syrian case were general principles that would shape the future of other nations as well. European statesmen and legal scholars had historically excluded non-Christians and non-Europeans from full membership in the family of sovereign nations. The Ottomans were deemed only marginal guests. But Wilson had opened the door to a universal regime of states’ rights. Syrians aimed to keep that door open.

Faisal and Rida said their good-byes over a formal lunch with two French officers, Colonel Antoine Toulat and Colonel Edouard Cousse. As Faisal’s liaisons to General Gouraud, Toulat and Cousse were destined to play a role in the coming independence struggle. As for Rida and Faisal, their January 15th meeting would launch an intense relationship for the next six months.

The next day, just as Faisal departed on the Damascus Road, an ominous rainstorm broke. The prince worried about the reaction of Syrian nationalists to the accord. They would reject the provisions granting control of foreign affairs and internal security to the French and independence to Lebanon. His plan was to persuade the cabinet that these terms were an interim step, not a capitulation.

The largest demonstration yet in Damascus greeted Faisal upon his arrival on January 17th. The Higher National Committee, led by Sheikh Kamil al-Qassab, had been planning it for weeks. Dr. Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar of the Syrian Union Party also played a prominent role at a general meeting of the Higher National Committee which organized opposition throughout Syria.

Qassab claimed that more than 100,000 people marched. Widows and daughters of war martyrs led the procession, followed by clergy of all faiths, committees of national defense, political parties, notables, the municipal council, civilian and military employees, farmers, doctors, pharmacists, journalists, the Arab Clubs, the schools of law and medicine, teachers, merchants, artisans, guilds, and leaders of the city neighborhoods and nearby villages.

They arrived at Marjeh Square with signs reading “The Arab Country Is Indivisible” and “Religion Is for God and the Country Is for All.” Others demanded full independence and a national army. Faisal greeted the demonstrators in front of city hall, promising to heed the people’s will. The crowd cheered when he proclaimed that he and the nation were fundamentally “in agreement for an independent, indivisible Syria.”

However, Faisal was not yet ready to cede authority to either the people or the Congress. At a large gathering at the Arab Club, he intervened in a debate between the Maronite priest Habib Istifan and Dr. Shahbandar. While Istifan pledged loyalty to Faisal, Shahbandar urged the assembly to recognize the government installed during Faisal’s absence and to follow the example of the Egyptian nationalist revolution against Britain. Dr. Shahbandar, Faisal responded sharply, should stick to his own profession, medicine.

The prince insisted that the current government was not an elected representative of the nation; it was merely a temporary, military administration. Since Syria was not yet recognized as a sovereign state, only he could represent the country, as a delegate of his sovereign father, Sharif Hussein of Mecca. “I am the spirit of the movement,” he declared. “I am the responsible person until a national assembly is elected, whereupon I shall relinquish my responsibilities and hand them over to the people.”

Faisal proceeded to dismiss the nationalist cabinet and restore Ali Rida al-Rikabi as head of government. He also supported the creation of a new conservative party to counterbalance the HNC. The Syrian National Party was led by anti-Fatat notables like the Congress vice president, Abd al-Rahman al-Yusuf, and Faisal’s wartime generals, Nasib al-Bakri and Sharif Nasir. They favored compromise with France over what they viewed as certain defeat for a self-proclaimed independent state.

But the prince could not turn back the political clock. Newspapers and Arab Club members publicly condemned the Clemenceau accord. Even Faisal’s personal physician, Dr. Ahmad Qadri, gave a press conference against it.

As a last resort Faisal called a meeting of Fatat leaders, but they too rejected the accord. Like Rida, they argued that it was a fig leaf for another French protectorate, as in Morocco and Tunisia. Faisal lost his temper and demanded that they file paper ballots to record their error for history. Then he called for elections for a new central committee. The new slate of Fatat leaders also voted against the prince.

*

On a brief visit to Beirut in early February, Faisal sought out Rashid Rida for advice. Over dinner, the prince asked the sheikh to return with him to Damascus to act as a mediator with Fatat and other nationalist leaders. Faisal pointed out that Rida knew Qassab and Shahbandar personally and had influence within Syria’s new Independence Party. But unlike those hotheads, Rida was a mature man of reason.

The sheikh hesitated. He had already left his family for more than five months and had refused an offer to work for the Damascus government. He was also appalled at Faisal’s naïveté. Faisal had foolishly trusted the British and now he appeared to be repeating the mistake with the French. But Rida also found Faisal an intelligent and eager student. In Faisal, Rida also recognized an opportunity to realize the Arab unity he had so long sought: If Syrians achieved independence, they might spark a revival across the Muslim world. So Rida agreed to Faisal’s offer, with a caveat that he would be no yes-man.

Rida advised Faisal to build solidarity through Islam. “We cannot establish Arab unity and restore the Arabs’ glory and civilization without Islam,” he contended.

Rida tied up his affairs in Beirut and took the train to Damascus on February 8th, 1920. That very night, he met with his old friend Kamil al-Qassab to catch up on the local news.

The very next day, a snowstorm hit the capital, locking it down for three weeks. The stretch of isolation proved to be a fertile period for political bargaining. Rida met Faisal nearly every day. In a fatherly manner, he dispensed the wisdom of age to the younger man. Rida also edited the prince’s speeches and reviewed his correspondence with Lloyd George and Sharif Hussein. The two men discussed how Faisal had blindly followed his father’s faith in the British, to no good end.

Rida also used his meetings at the royal residence to advance his ideas on building Arab strength through a league of states, based in Mecca. He argued that the key to achieving political unity, internationally and within Syria, was to build cooperation from the ground up, not to impose unity from above by subduing the different parties.

Rida drew his wisdom on democratic politics not from reading European or American textbooks but from his own experience in Ottoman politics. The Young Turks had betrayed the 1908 constitutional revolution by repressing opposition parties. Difference was natural, Rida explained to Faisal. In a righteous government, parties were free to debate and thereby minimize the harm in their differences by finding points of consensus.

To demonstrate his ideas, Rida invited the prince to a rally on February 9th. As the wind blew drifts of snow, the city’s elite gathered in tents warmed with carpets. Sheikh Kamil al-Qassab delivered “a long and eloquent speech” on how the nation would accept nothing short of absolute independence. Faisal gave a speech in response, in which he felt compelled to agree.

Rida advised Faisal to build solidarity through Islam. “We cannot establish Arab unity and restore the Arabs’ glory and civilization without Islam,” he contended. He also proposed ways of bridging differences among various Islamic sects. The prince was so enthusiastic that he asked Rida to move his family and magazine to Damascus from Cairo. Rida assured Faisal that he would stay to build a righteous government based on the ideas of Islamic reformists.

Rida firmly believed that Islam and democracy were not only compatible but also a necessary combination for ethical governance. His views were not universally popular, as he discovered when the dean of the newly founded law school invited him to give a lecture. Anticipating opposition, Dr. Ahmad Qadri, Faisal’s personal physician, warned Rida not to deliver the speech.

But when a secularist law professor objected to hosting a religious lecture in a state school, the dean overruled him. With Faisal in attendance, Rida gave his lecture, titled “Arab-Islamic Civilization and European Materialist Civilization.” The prince liked the lecture and praised Rida for his mature views, Qadri later confided.

In these crucial weeks of snowed-in consultation, Rida became a pivotal player in uniting Faisal and the Syrian Congress on a plan to declare independence. But it was not Rida who finally persuaded the prince to abandon negotiations with the French. Faisal realized the game was over when his own father, Sharif Hussein, published a personal attack on him and on the January 6th accord in a Cairo newspaper. An opposition paper in Damascus reprinted Sharif Hussein’s demand for complete independence with no strings attached.

The article launched a new round of public protest. Delegations arrived at Faisal’s royal residence, demanding that he obey his father. The prince staunchly defended the need for the accord. On February 15th, after Qassab gave a speech viciously attacking Faisal’s policy, the HNC took a formal vote against the accord and against all compromise.

Rida urged Faisal to reconcile with Qassab and Shahbandar. The nation’s future depended on it, he warned. Faisal acquiesced and invited Qassab and Shahbandar to dinner at the royal residence the next evening, February 16th. The three argued fiercely. Qassab insisted that the nation was ready to rise up en masseto claim independence.

The time was ripe, since French forces had relocated from Syria to confront the Turkish nationalists in Cilicia. Faisal responded that the nation needed firm leadership, or else blood would run in the streets. No common ground was found. The dinner ended, however, with promises to keep their disagreement secret.

In desperation, Faisal cabled to Gouraud in Beirut pleading for a sign of French support for the terms of Arab independence promised in the January accord. “The people are waiting for actions by the French government in support of my efforts in this regard,” he wrote. Their fears were heightened now, he explained, “since the publication of the message in which His Majesty my father advised me to demand independence for all the Arab regions.”

But Faisal’s effort to use his father’s public warning as leverage with the French failed. Word of the royal rift had already leaked out. Colonel Cousse, the French liaison in Damascus, reported that it had revealed Faisal’s weakness. Gouraud reported to Paris only that Faisal appeared incapable of upholding his promise, made on January 6th, to maintain order in Syria.

The staff in Paris agreed with Gouraud to make no more concessions to “extremists.” They also agreed to reaffirm their advice to Faisal, that he should not return to Paris to finalize the accord until he could demonstrate solid political support for it.

Faisal received no response from Gouraud until March 2nd. The general assured the prince that France did not intend to rule the East Zone directly, but that it would defend its position in Lebanon. Faisal and Zaid held a last-ditch meeting at Rikabi’s home in the hope of persuading several Fatat leaders. But the political pendulum in Damascus had swung toward an alliance for independence.

*

In late February, even as he continued to meet Faisal, Rida attended Independence Party meetings on reconvening the Congress and drafting a declaration of independence. (The party was the public face of the secretive Fatat.) During several meetings held at Ali Rida al-Rikabi’s home, a majority in the party agreed with Rashid Rida that the Congress must be established as the nation’s representative—against Faisal’s dynastic claims. Congress, not Faisal, would have to declare independence in the name of the people. As the snow began to melt in the last week of February, the Independence Party summoned its members from Lebanon and Palestine.

Against minority proposals to hold new elections for Congress, Qadri and Shahbandar argued that Syria must declare independence immediately. The Congress could proceed legitimately based on the elections of June 1919. It must now exploit the window of opportunity that had opened with the transfer of French troops from Syria to Cilicia, where they were battling Turkish nationalists.

Some party members objected that Syria’s status had to be defined at the peace conference, in the treaty on the Ottoman Empire. The conference had only now opened discussions on the matter, after completing treaties with the other Central Powers since summer. But Qadri and Shahbandar insisted that Syria’s right to provisional independence under Article 22 of the League covenant had already been ratified by France and Britain as part of the Treaty of Versailles, which had taken effect on January 20th.

Should the Syrian state have a top Islamic official, like the Ottoman Empire’s Sheikh al-Islam? Should Islamic law be integrated into the regime?

Meanwhile, Izzat Darwazeh, deputy from Nablus, Palestine, and others drafted a declaration of independence. At a subsequent party meeting, Rida proposed amendments to the draft. “He left out the most important of my proposals,” Rida wrote, “which is to base independence on the natural right of the people to freedom and independence . . . and on the fact that Syrian Arabs and others rebelled successfully against the Turkish government.” These points must be coupled with Syria’s rights as defined by Article 22, he argued.

The palace was likely aware of these meetings, given that Rida requested copies of supporting legal documents from Awni Abd al-Hadi, who was Faisal’s secretary and a leading member of Fatat. Abd al-Hadi had returned to Damascus with Faisal in January and had taken a personal interest in the plans for independence.

He felt especially anxious because Britain had already claimed a mandate over Palestine, thereby separating his hometown, Nablus, from Syria. While Abd al-Hadi continued to lose weight, owing to anxiety, Rida eased his worries by indulging in the delicious cuisine of his homeland. In his diary, he noted he had gained four kilograms in February.

On February 29th and March 1st, the Independence Party opened debate on the role of Islam in the government. Until then, members had only vaguely talked of a constitutional monarchy with Faisal as its king and with Islam as its religion. Should the Syrian state have a top Islamic official, like the Ottoman Empire’s Sheikh al-Islam? Should Islamic law be integrated into the regime?

One side responded no, there was no need for a cabinet minister on Islamic affairs. The other side argued that a minister must govern Islamic courts and endowments. They asked Rida for his view.

The Syrian state would gain much prestige and support if it had an Islamic component, Rida argued. The caliphate had helped the Ottoman regime to survive, despite its military defeats, because millions of Muslims supported it. Second, Islam would strengthen Syria’s confederation with Iraq and Arabia. The only bond uniting Arabs across the regions was their common religion. “Syria cannot remain as an independent kingdom unless it is united with other Arab countries surrounding it,” he pointed out.

Third, he said, most ordinary Muslims would consider a secular state unfamiliar and illegitimate. “They would overturn it in favor of a religious one at the first opportunity,” Rida claimed. “Therefore, our Sharia should be the main source of needed legislation, even if the government is not Islamic.” Rida proposed that the government include a minister for religious affairs as well as Islamic scholars on its staff.

Such a state would not be a theocracy, he assured opponents. Nothing in Islamic law contradicted a civil state—only scholars of the strictest schools believed that there was any contradiction. The meeting disbanded without resolving the question.

Faisal was by then convinced that he should reconvene the Congress. While critics later claimed Faisal was bullied by “extremists” into accepting the Declaration of Independence, the record of his sustained discussions with Rida and with party members suggests otherwise. Faisal recognized that popular opposition to the French accord was overwhelming.

He also recognized the legality of Syrian independence under international law. And he understood the need to establish an independent state as a fait accompli, given that the Americans were no longer arbiters against colonial aggression at Paris. In the end, Faisal was likely happy to hand responsibility for such a fateful decision to the Congress.

The prince did, however, worry about his father’s reaction. When a new flag was proposed, he insisted on pleasing his father by maintaining the stripes and red triangle of the Hijazi flag flown during the Arab Revolt. Party members agreed. The new Syrian flag would differ only by the addition of a white star inside the triangle.

__________________________________

Excerpted from How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove. Copyright © 2020 by Elizabeth F. Thompson.

Elizabeth F. Thompson

Elizabeth F. Thompson is a leading historian of the modern Middle East and Mohamed S. Farsi Chair of Islamic Peace at American University’s School of International Service. She is the author of two previous books, Colonial Citizens: Republican Rights, Paternal Privilege and Gender in French Syria and Lebanon, winner of two national book prizes, and Justice Interrupted: The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East. Her newest book, How the West Stole Democracy From the Arabs, is out from Grove.